MLK’s ‘dream’ alive but unfulfilled 60 years after March on Washington

Martin Luther King III is conflicted.

On the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and his father’s landmark “I Have a Dream” speech, King III is still wondering how far the country has come.

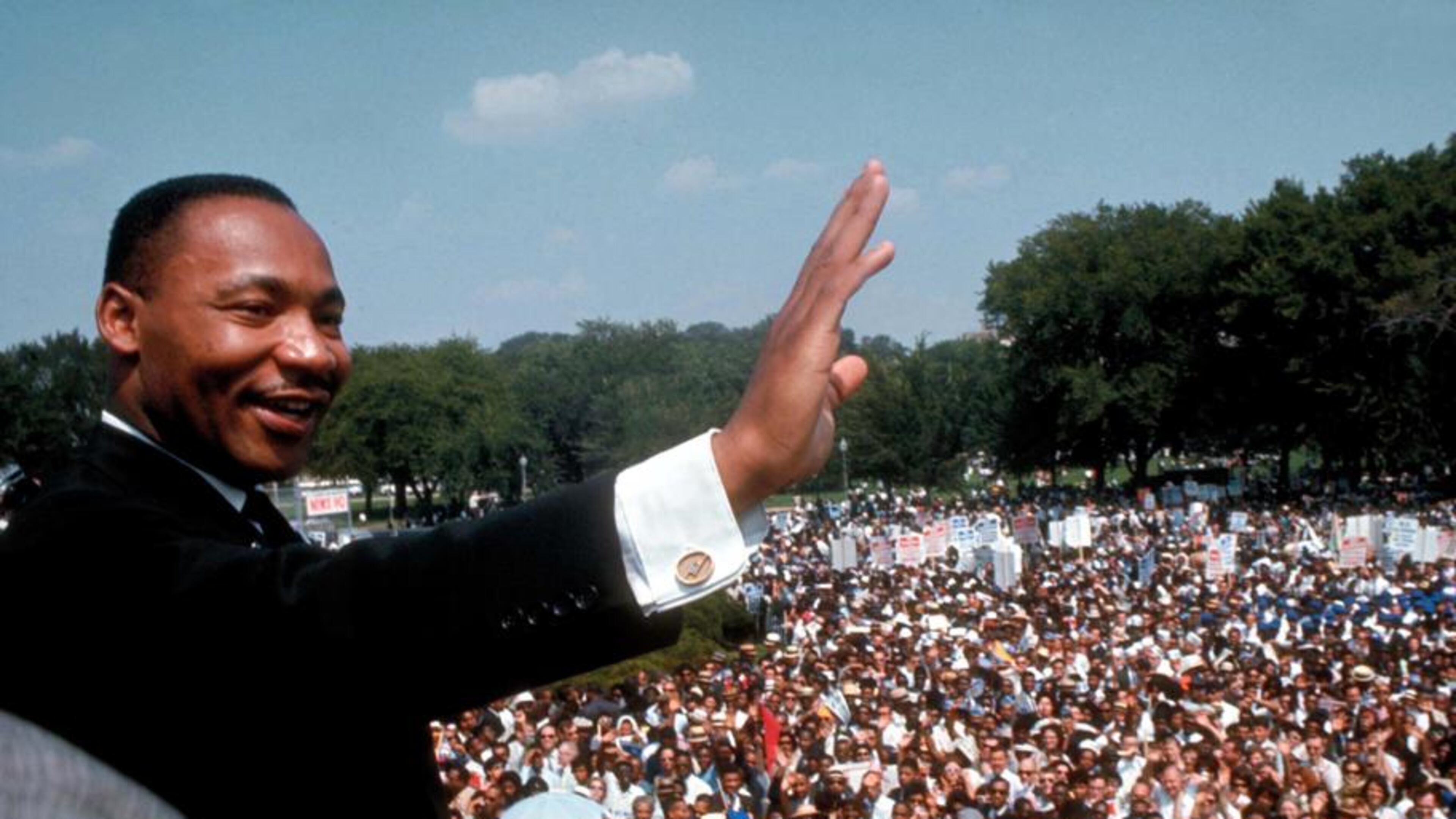

The 1963 march, attended by more than 250,000 people, laid the foundation for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and might have sewn up the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize for Martin Luther King Jr.

In one of the most iconic lines of his speech, King Jr. imagined that “my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.”

But the demands for economic equity, social justice and racial equality still have not been met, says King III, his oldest son. He points to wage disparities, recent attacks on voting rights and LGBTQ protections, local school boards banning books, the overturning of Roe v. Wade, and the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

“The unfortunate part is that Yolanda Renee had more rights when she was born in 2008 than she has now,” King III said of his teenage daughter.

“She has fewer rights than her mother, grandmother and great-grandmother. Is freedom, justice and equality here? No. There have been great strides, but unfortunate setbacks,” added King III, who is 65 years old.

U.S. Rep. Lucy McBath also puts her reflections on the March on Washington in the context of her son, Jordan, who was killed in 2012 at age 17. She says his death at the hands of a white man who complained about the teen’s loud music is proof that the work of her parents, who were leaders of their local NAACP chapter and attended the March with toddler McBath in a stroller, is unfinished.

McBath said her father, who also was editor-in-chief of the Illinois NAACP’s newspaper, would have been devastated if he had been alive when Jordan was murdered. “He fought in that movement to prevent these kinds of tragedies happening to our people based upon bigotry and discrimination,” said the Marietta Democrat.

Tens of thousands of people are expected to gather Saturday at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington to mark the anniversary of the historic civil rights march, accompanied by King III and his sister Bernice King. King III plans to say that his father’s “dream” of a just America remains a work in progress and to call on Congress to pass federal voting rights legislation after the Supreme Court in 2013 invalidated a critical part of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

“Opposed to a celebration this is a rededication,” King III said. “On Jan 6, we saw an insurrection. Today, I hope to see a resurrection of ideas that move our country forward, not backward.”

In Atlanta on Saturday, the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park will host a local commemoration with Rev. Dr. Albert Paul Brinson, who participated in the March on Washington and has a longtime relationship with the King family. The park also will hold viewings of the “I Have a Dream” speech and conduct interpretative talks inside the Historic Ebenezer Baptist Church throughout the day.

Looking back

The 1963 march mobilized civil rights supporters to lobby for jobs, housing, voting rights and fair wages.

Martin Luther King Jr. was chosen to be the final speaker of the night at the Lincoln Memorial and was given nine minutes. But at around the nine-minute mark, some say with the urging of gospel great Mahalia Jackson, King shifted into the “dream” portion of the speech, which was not planned.

U.S. Sen. Angus King of Maine remembers watching the speech as a 19-year-old, perched in the limbs of a tree lining the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool.

Martin Luther King Jr. started off with prepared remarks that included a metaphor about the nation’s debt to Black people. After Jackson encouraged him to talk about “your dream,” the remarks became iconic, the senator said.

“That was when the speech really grabbed people, and it was a turning point,” he said. “His words that day that really grabbed the conscience of America.”

Andrew Young, who attended the 1963 march as a staffer with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, feels the same way.

“That last five minutes was all that people remember, but that established the credibility of a non-violent movement,” said the former Atlanta mayor and United Nations ambassador.

“Everybody was afraid of 100,000 people, but it turned out to be 250,000. And it was perfect decorum and no violence,” Young added. “I think the only thing illegal was people putting their feet in the reflecting pool to cool off. People were awestruck by the power of this movement.”

Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton, who represents the District of Columbia, takes note of all the work that came before the crowd gathered on Aug. 28, 1963. She was a Yale law student at the time but spent the summer months registering voters in Greenwood, Mississippi.

One of the people who escorted her to the bus to begin her trip down South was Medgar Evers. She was horrified to learn that when he got home, he was confronted by a segregationist and assassinated.

Norton and other women who were involved in march organizing and planning also seethed, although mostly privately, when Dorothy Height was barred from having a speaking role. Height was the leader of the National Council of Negro Women, one of the “big six” civil rights organizations that spearheaded the march.

“I’ve seen some sexism in my life but never so blatant,” Norton recalls today.

Bernice King said her mother went to the march and hoped to meet with President John F. Kennedy at the White House, but was barred from the meeting.

Still, the women kept working and helped ensure the event’s success. Height took her seat on stage to the left of the podium and can be spotted in several photographs taken during King’s speech.

The decision to let King speak last was not without debate. King had not planned the march and the SCLC was the “new kid on the block,” according to Young.

“But Martin was rising. People wanted to see Martin,” Young said.

‘One Day’

Five months to the day of that famous speech, Coretta Scott King gave birth to the couple’s fourth child, Bernice. Neither she nor any of her siblings attended the march.

Early on, for Bernice King, the march was part of family lore. Something her father did. But the head of the Atlanta-based King Center nonprofit didn’t fully understand the context until 1983, when her mother was planning events for the 20th anniversary.

“I understood that ‘I Have a Dream’ catapulted the March on Washington to a platform that perhaps it wouldn’t have had without it,” Bernice King said. “It is the most recited and best-known speech in the world. It is part of motivating people, educating people and inspiring people.”

Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968. Coretta Scott King died in 2006. Yolanda, Bernice’s older sister, died a year later.

Young plans to attend this weekend’s anniversary march in Washington along with several members of King’s family, as well as Al Sharpton, who helped organize the event through his National Action Network.

Young noted that in the improvised “dream” portion of the speech, King never said “tomorrow.” Rather, King said that “one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

“That was significant,” said Young, who is 91 years old. “It gave us hope without a deadline. We are still living with that hope.”