Vinnette Carroll: Broadway trailblazer in directing Black stories

The late Broadway director Vinnette Carroll set out to become a clinical psychologist but early in her career, acting and theater became a driving force.

She was the first Black woman to direct a play on Broadway with “Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope” and was a pioneer in theater, taking risks as a director against the backdrop of the Vietnam War and Civil Rights Movement.

In 1971, Carroll staged Irwin Shaw’s dramatic anti-war story “Bury the Dead” about young men who were killed and refused to lie in their graves. She transformed it into an Off-Broadway musical renaming it “Step Lively Boy” after a satirical song written by Micki Grant. It marked her first collaboration with Grant, who was a lyricist/composer and performer.

In 1972, Carroll directed Grant’s musical, “Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope” featuring a story on Black life. It was nominated for four Tony Awards including Carroll for best direction and Grant for best actress.

“She was very instrumental in bringing the Black diaspora together and represented on Broadway,” Savanna Washington said of Carroll. Washington, professor of media studies at The New School in New York City performed in-depth research on Carroll in 2018 for the school’s Women’s Legacy Project.

Tony-nominated “Your Arms Too Short to Box With God,” a story conceived by Carroll and inspired by the Gospel of Matthew was performed in Spoleto, Italy, before reaching Broadway for the first time in 1976. The production garnered four nominations including best director and book for Carroll, and a Tony win for a featured role for actress Delores Hall.

While Vinnette Carroll is not a name widely known today, the playwright’s impact extends from the 1950s into 2022 in bringing diverse storytelling to theater productions and actors who performed in them.

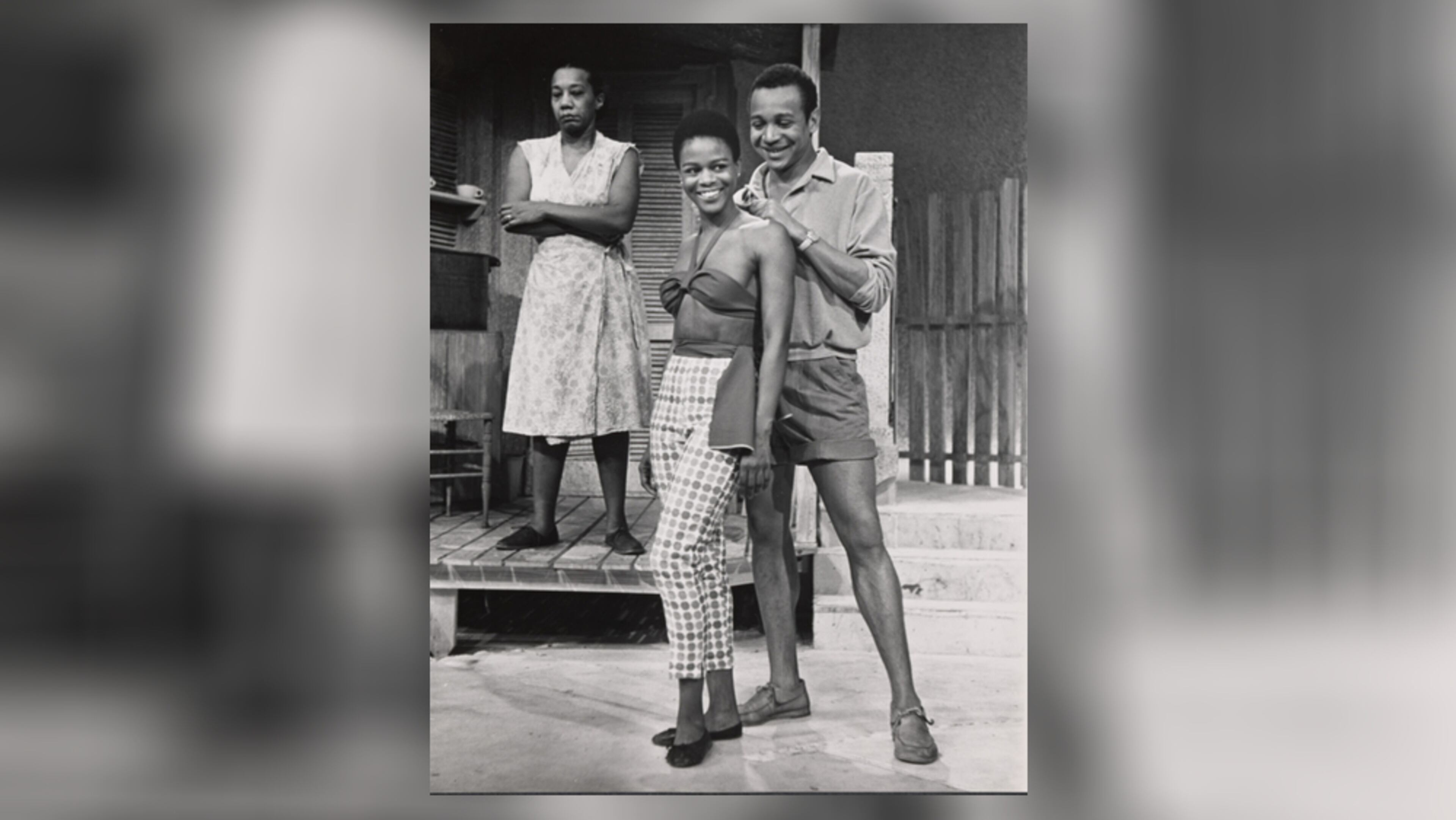

During the 1978 documentary “Black Theater: The Making of a Movement” Carroll remarked how her production 20 years earlier of “Dark of the Moon” was a “golden time” even though actors of color weren’t getting jobs in major shows.

Her cast in that 1958 production at the Harlem YMCA included Cicely Tyson, James Earl Jones, Roscoe Lee Brown, Rosalind Cash and Clarence Williams III.

“...There’s a fullness and richness to Black people that needs expression in the same way as our need for catharsis that comes from doing plays specifically dealing with our specific problems...,” Carroll said in the documentary.

Carroll was born in New York City in 1922 and raised in an upper-middle-class family in the Sugar Hill section of Harlem. For part of her childhood, Carroll and her sister Dorothy lived with their grandparents in Falmouth, Jamaica, while her father completed dental school at Howard University.

After high school, Carroll followed a collegiate track to become a clinical psychologist. In the late 1940s, while completing the required course work for her doctorate degree in psychology from Columbia University, Carroll was also studying acting with Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio in New York City. That led her to two other acting teachers — Stella Adler, as well as Erwin Piscator, founder of The Dramatic Workshop at The New School. He was training young actors at the time such as Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando and Tony Curtis.

Washington said Piscator offered Carroll a full scholarship to his workshop after seeing her audition. His workshop was comparable to The Actor’s Studio Drama School today, she added.

“(Piscator) was world-renowned,” Washington said. “He was the elite of the elite. And (Carroll) was the first Black woman to be in that program fulltime.”

Washington discovered through documents provided by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture that Carroll left her work as a psychologist assisting public schools through New York City’s Bureau of Child Guidance to teach drama at the former High School of Performing Arts.

Carroll founded Urban Arts Corps through the New York State Council for the Arts in 1967 to make the arts and stage more accessible to Black and Puerto Rican youth in underserved communities.

The Urban Arts program created a repertory company in which Carroll produced the plays that were perfected before they were staged on touring appearances around the U.S. and world or as Broadway productions, Washington said.

“…She (created) this gathering place that seemed to be a safe space for people,” Washington said of Urban Arts. “They seemed to stay in the fold until they became a hit themselves. We’re talking about artists of color. The mainstream theater was hostile.”

Urban Arts Corps ended in 1983 according to New York Public Library Manuscripts. Carroll partially retired to Fort Lauderhill, Florida in 1980 and was a writer-director in residence at Spelman College in 1990.

In Florida, she founded the Vinnette Carroll Repertory Company that performed in parks and libraries before finding a home in a former church through state and county grants, according to a 1988 video in the Miami-Dade County Archives.

Carroll passed away in her Florida home in 2002 due to complications from diabetes and heart disease, a New York Times report said. She was 80 years old.

Washington said Carroll’s father, a native of the West Indies, preferred her to have the security of the medical profession instead of a career in theater.

“He really established this life that was amazing and then to have this kind of rebel child,” Washington said. “But she still was like her father in a lot of ways in that he came here to make a change, and his daughter went on to be on this amazing path creating change.”

Black History Month from AJC

This year, the AJC’s Black History Month series will focus on the role of resistance to forms of oppression in the Black community. In addition to the traditional stories that we do on African American pioneers, these pieces will run in our Living and A sections every day this month. You can also go to ajc.com/black-history-month for more subscriber exclusives on the African American people, places and organizations that have changed the world.

Stories about resistance: Choose from a list of daily stories

Health and wellness series from 2022

Unapologetically ATL – For coverage of Black Atlanta culture

READ MORE