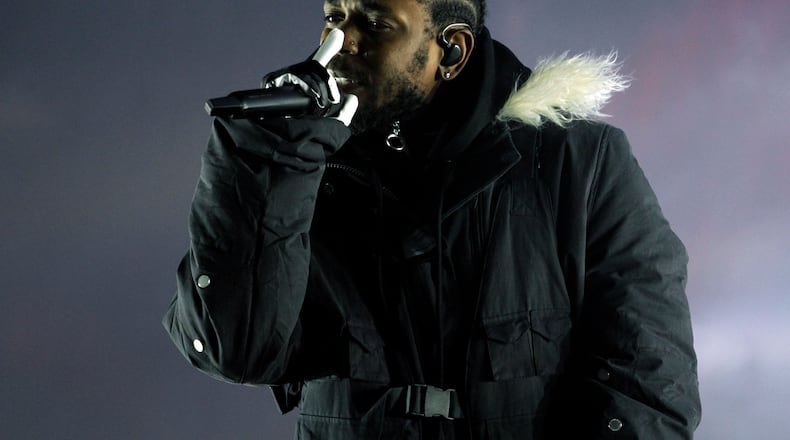

Before Kendrick Lamar became the first rapper to win the Pulitzer Prize, the Compton, California, artist had spent years crafting literarily inspired records.

Lamar’s 2018 win — for the album “Damn” — came as American academia has in recent years grown to accept hip-hop’s contributions. It was a triumph for hip-hop, a genre long held by some musical academics as a form less likely to produce poetic lyricism and storytelling than other popular styles. But the victory, which marked a departure for an award that had always gone to classical or jazz musicians, was for Lamar, too. Lamar followed a tradition of brilliant lyricism in hip-hop, but his award was widely praised as well-earned for the 33-year-old.

“Kendrick doesn’t forget he comes from a bloodline of Black musicians. Kendrick also doesn’t forget the history of America. You listen to him, and you hear a Black man who observes the world as he sees it,” said Yoh Phillips, music journalist and co-host of “Sum’n to Say,” the popular Atlanta-based hip-hop podcast. “He’s my favorite kind of rapper, one who is aware, thoughtful, and critical of the times.”

Beginning in the 2000s, the rapper, whose full name is Kendrick Lamar Duckworth, got notice for the stories he wrote about growing up in Compton, brushes with the law, systemic racism, the grip of poverty, gangs and heavy-handed gang cops. Lamar’s 2012 album “Good Kid, M.A.A.D City,” nominated for album of the year at the 2014 Grammy Awards, interwove those tales to construct a broader narrative about a central character. It cast Lamar as his younger self, trying to navigate coming from a place where, as he puts it, kids get used to violence and feeling under siege by all the forces competing for their attention: the neighborhood, the Pirus and the Crips, the police, the family, the art and a dream.

By the time 2018′s “Damn” arrived, it was clear Lamar had grown, even after the feat that was “Good Kid, M.A.A.D City.” On “Damn” similar themes return, but Lamar writes about them from a different place in life. In 2012, he was rising. In 2018, he had risen and was chosen to do the soundtrack for the blockbuster movie, “Black Panther.” On “Damn”, he looks back on the corrupting and pursuing forces he faced growing up, but there is more distance, more perspective and, at times, more righteous anger.

“His songs can go from discussing religion, to exploring his history with depression, and then shift to him making fun of how immature he was when he was a kid,” said Darrelyn Hughes, an attorney in Duluth. “You can dance, laugh, and cry when listening to a single Kendrick song.”

While other artists preen on social media and in frequent interviews, Lamar seems to like to let the songs speak. As with many popular but private artists, he can be misunderstood and run up against a problem encountered by musicians of any genre that inspires people to dance: sometimes people just want a good beat and simple words to make them forget their troubles.

All over the country, this was the reaction to Lamar’s 2012 hit, “Swimming Pools (Drank).” It had the good beat, but everyone didn’t listen close enough to the lyrics to realize the song is about losing yourself to the perils of abusing alcohol. Yet Phillips, the music journalist, heard the song at many clubs and house parties. Revelers would shout, “Pour up, drank, pour up, drank,” the ironic hook intended to inspire you to stop drinking.

Within a few years, Lamar was becoming less misunderstood, gaining recognition with a slew of awards.

But the Pulitzer? It was recognition from the nation’s highbrow scribes, given out by Columbia University, no less.

“It was one of those things I heard about in school,” Lamar told Time magazine, “but I never thought I’d be a part of it. (When I heard I got it), I thought, to be recognized in an academic world . . . whoa, this thing really can take me above and beyond.”

BLACK HISTORY MONTH: Throughout February, we’ll spotlight different African American pioneers ― through new stories and our archive collection ― in our Living and Metro sections Monday through Sunday. Go to AJC.com/black-history-month for more subscriber exclusives on people, places and organizations that have changed the world, and to see videos on the African American pioneers featured here each day.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured