Somehow it seems fitting that the criminal corruption trial of CEO Burrell Ellis is underway as 10 candidates fight it out for a commissioner post in DeKalb County.

Ellis’ indictment two years ago started a game of political musical chairs. District 5 Commissioner Lee May jumped into the CEO’s spot, leaving his own seat vacant. And it has remained so ever since, as commissioners battled over who should fill it.

A special election Tuesday will begin the process of determining, once and for all, whose bottom should warm the seat that represents southeast DeKalb for the next 18 months.

The candidates battling for the spot include lawyers, business people, activists, failed candidates, a congressman’s spouse, a whistle blower and even a political insider who has announced that he passed a lie detector test. (More on that later.)

It does make for a memorable campaign slogan: “Look, my mouth is moving but the needle isn’t!”

District 5 has suffered all sorts of indignities in recent years: a rash of foreclosures, low graduation rates and high crime stats, all compounded by 22 months of having no district commissioner to articulate the frustrations of its 145,000 citizens. Not long ago, residents showed up at a county board meeting wearing T-shirts with slogans that expressed their displeasure at being represented by an empty armchair.

So, finally, Interim CEO May did the right thing and gave up his District 5 seat, allowing the process to move from stalemate to election. My guess is May is banking on the “interim” being soon removed from his title.

Announcing an election to fill an empty seat is akin to rattling a bowl of kibbles at a dog park you’re going to attract an instant and enthusiastic crowd.

Last year, when the call went out for people to get appointed to the job, 19 people raised their hands. So perhaps it’s understandable that commissioners couldn’t settle one of them. This year the call went out for an election, which is a more difficult process than just being handed a job, and many of the same crowd stepped forward.

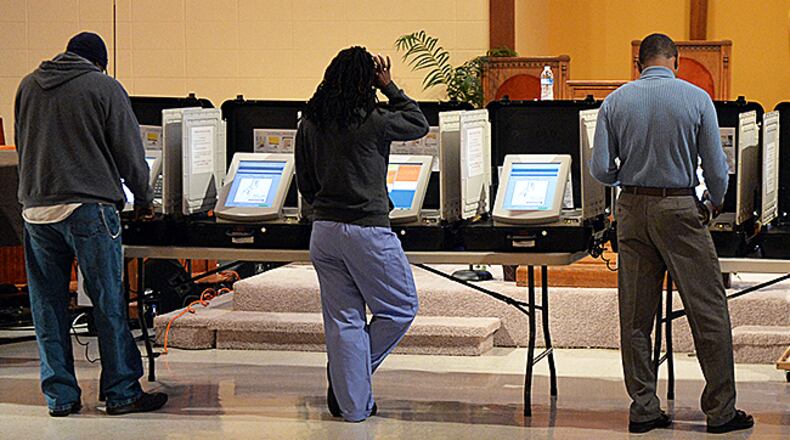

But despite the heartwarming public-spiritedness of the candidates and the ensuing crowded stages at forums, the public is largely yawning. So far, during two weeks of early voting, barely 150 people have bothered to cast ballots. That’s right, the district has been without adult supervision for two years, and corruption is routinely uncovered, but just 10 people out of 95,000 registered voters come in each day to vote.

Ouch.

Maxine Daniels, DeKalb’s elections director, remains optimistic, thinking the compressed election cycle has caused voters to delay casting their ballots so they can compare and contrast the candidates.

Even so, special elections are notoriously unattended. She figures 5 percent is a normal turnout. That means maybe 5,000 voters will turn out and two candidates can survive to the July runoff by garnering as few as 1,000 votes each.

To be fair, and I learned this in journalism school, I’m going to list all the candidates:

- Gregory Adams, a pastor and Emory University cop who ran against Ellis in 2012.

- Harmel Deanne Codi, a former DeKalb County financial officer who resigned after she felt her allegations of bid-rigging were being ignored.

- Jerome Edmondson, who owns call centers and also lost to Ellis.

- Gwen Russell Green, a DeKalb school librarian. And a poet.

- Vaughn Irons, the CEO of a property development company and a development authority official, who has loaned himself $13,500 to run.

- Mereda Davis Johnson, a lawyer and wife of U.S. Rep. Hank Johnson. She leads the pack by far, money-wise, having raised $21,000.

- Gina Mangham, a lawyer and activist who lost to Lee May in 2012.

- Kathryn Rice, founder of the South DeKalb Improvement Association and leader of a movement to form the city of Greenhaven. She lost to Commissioner Stan Watson in 2010.

- Kenneth Saunders, a technology consultant and a leader of the Hidden Hills Civic Association.

- George Turner, a retired MARTA manager whose recommendation for appointment to the commission caused endless debate on the board.

I spoke with Codi and Rice, two people who might make some difference if elected.

Rice, who has raised $2,400 in contributions, helped create the South DeKalb Improvement Association because that area needed just what the title suggested. She has picked up litter and campaigned to get businesses to invest in the area. Lately, her group has been documenting continuously low housing appraisals that keep people from getting loans to buy homes in South DeKalb.

Rice is thoughtful and smart and talks about "vision" and needing a "clean slate," although she won't go so far as saying DeKalb's leadership is incompetent. "I'd say dysfunctional," she said, because she is also diplomatic.

Codi, as a DeKalb employee, put it on the line, going to her superior, and then her superior's superior (with the first superior simmering at the table) and finally the interim CEO to complain about doings she saw as hinky. She told her bosses the politically connected Irons' company got a $500,000 contract "without going through the procurement process."

She also spelled it out in a six-page, single-spaced grievance letter of alleged wrongdoings and shortcuts, devoting a full page to Irons, who as a development authority member had a built-in conflict doing business with the county. Irons has denied any wrongdoing and proffered the lie detector results to put all this talk of hanky-panky to rest.

Codi reasons that she has toiled in the belly of the beast that is DeKalb and has the guts to help change it. “These other folks are riding on my coat tails, standing on my shoulders,” she said with a Caribbean lilt. “I’m the one who put herself out there.”

She is also betting on herself, loaning her campaign $6,700 while picking up $3,500 in contributions.

It’s a risk. Codi lives in a fashionable home that is under water to the tune of $47,000, just like many of her neighbors, so she’s not exactly flush. But the same gumption that caused her to call out the DeKalb Way as a county employee could make her a force for change.

At least, there’s always hope.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured