A testament to black businesses: Odd Fellows Building observes centennial

Velma Maia Thomas Fann looks at the cornerstone of the six-story red brick Odd Fellows Building and reads aloud some of the names etched there.

There was B.S. Ingram and Dr. R.H. Cobb and R.E. Pharrow.

And then there was B.J. Davis.

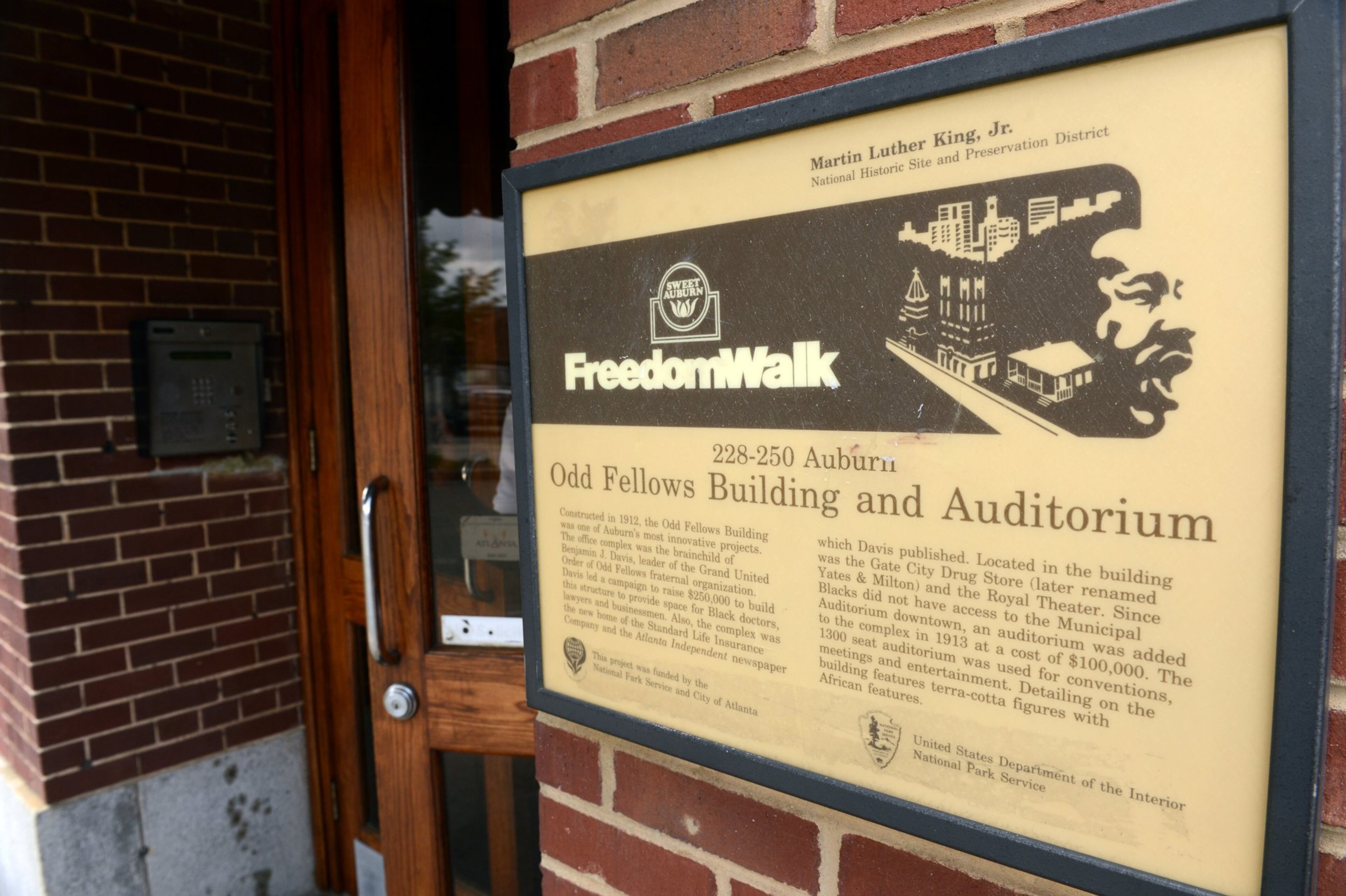

Benjamin J. Davis, a businessman and publisher of the Atlanta Independent newspaper, led the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows in construction of the building. The main office was built in 1912, followed by the auditorium in 1913.

In its heyday, the Odd Fellows Building and the block it occupied on Auburn Avenue were where many black Atlantans did business and socialized.

“This is a crucial building if you want to know anything about Atlanta history, particularly African-American history,” said Fann, an Atlanta researcher and author. The buildings ”were built and financed — debt-free and on time — by African-Americans, many just one generation removed from slavery.”

As the building continues to observe it 100th anniversary, Fann hopes to expose more people to its storied past. She is collecting oral histories and photographs of people who used to work there, owned businesses or just remember it as a part of the fabric of black life in Atlanta.

The auditorium and roof garden served the site of many of black Atlanta’s social functions, dances and live music. Cab Calloway wowed audiences there. So did Bessie Smith and James Brown.

Janis Perkins and her husband, Robert, bought the property in 1987 and restored it.

Over the years, the building and auditorium had fallen into disrepair. “It was almost in a shambles,” she said. “If you walked on the second floor, you had a fear of falling through, and it was inhabited by birds, squirrels and other four-legged creatures.”

But the couple saw the potential to return it to its more vibrant days.

Dan Moore Sr., the founder of the nearby APEX Museum, was instrumental in finding new owners for the Odd Fellows Building and auditorium. “The Odd Fellows Building is very critical and important,” he said. “It’s one of the few remaining building on the avenue built by black contracts at the turn of the century.”

For Fann, it all began as a class project.

In 2011, she was working on a certificate in heritage preservation at Georgia State University. For one class, she decided to tell the story of the Odd Fellows Building and soon became hooked on its past.

“A lot of times we hear about our struggles but not our successes,” she said.

Fann hopes to garner interest as more focus is placed on Auburn Avenue. The city is working on a streetcar project that many hope will increase traffic, tourism and business in the area.

Her work also comes as the street of dreams continues to face obstacles. In addition to the streetcar project, Georgia State is expanding its footprint in the area.

Last year, the Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation included the Sweet Auburn Commercial District in its annual Places in Peril report.

It, perhaps, adds urgency to her work.

“This draws attention to the buildings so people will understand why that historic district is so important,” Fann said. ‘We want this to stay part of our history.”

Mark C. McDonald, president and CEO of the Georgia Trust, applauds Fann’s efforts to help keep the Odd Fellows story alive for future generations.

“Atlanta’s preservation record when it comes to residential historic districts is pretty good when you look at neighborhoods like Edgewood, Inman Park and Druid Hills,” he said. “However, the attitude of Atlanta toward the commercial historic areas leaves much to be desired. I think the reason is that there is so much commercial pressure on those areas and that money and new construction tends to overwhelm the respect for our past.”