Scientists just did something Einstein didn’t even think was possible

In 1936, Albert Einstein penned a research paper on his theory of relativity predicting that the weight of stars can be measured by the bending of passing light, a phenomenon now called gravitational microlensing that scientists have since observed.

But in that paper, published in the journal "Science," Einstein said, "Of course, there is no hope of observing this phenomenon directly," largely because stars are so far apart from one another.

Contrary to Einstein’s statement, astronomers studying the skies with NASA’s Hubble Telescope did just that this week when they directly measured the mass of a white dwarf star using his gravitational lensing theory.

The team, led by astronomer Kailash Sahu of the Space Telescope Science Institute, directly measured the mass of the dwarf star Stein 2051B by putting it on an interstellar balance scale.

The scientists observed Stein 2051B and its partner star, Stein 2051A, with the Hubble Space Telescope.

» RELATED: What are gravitational waves; why Einstein was right

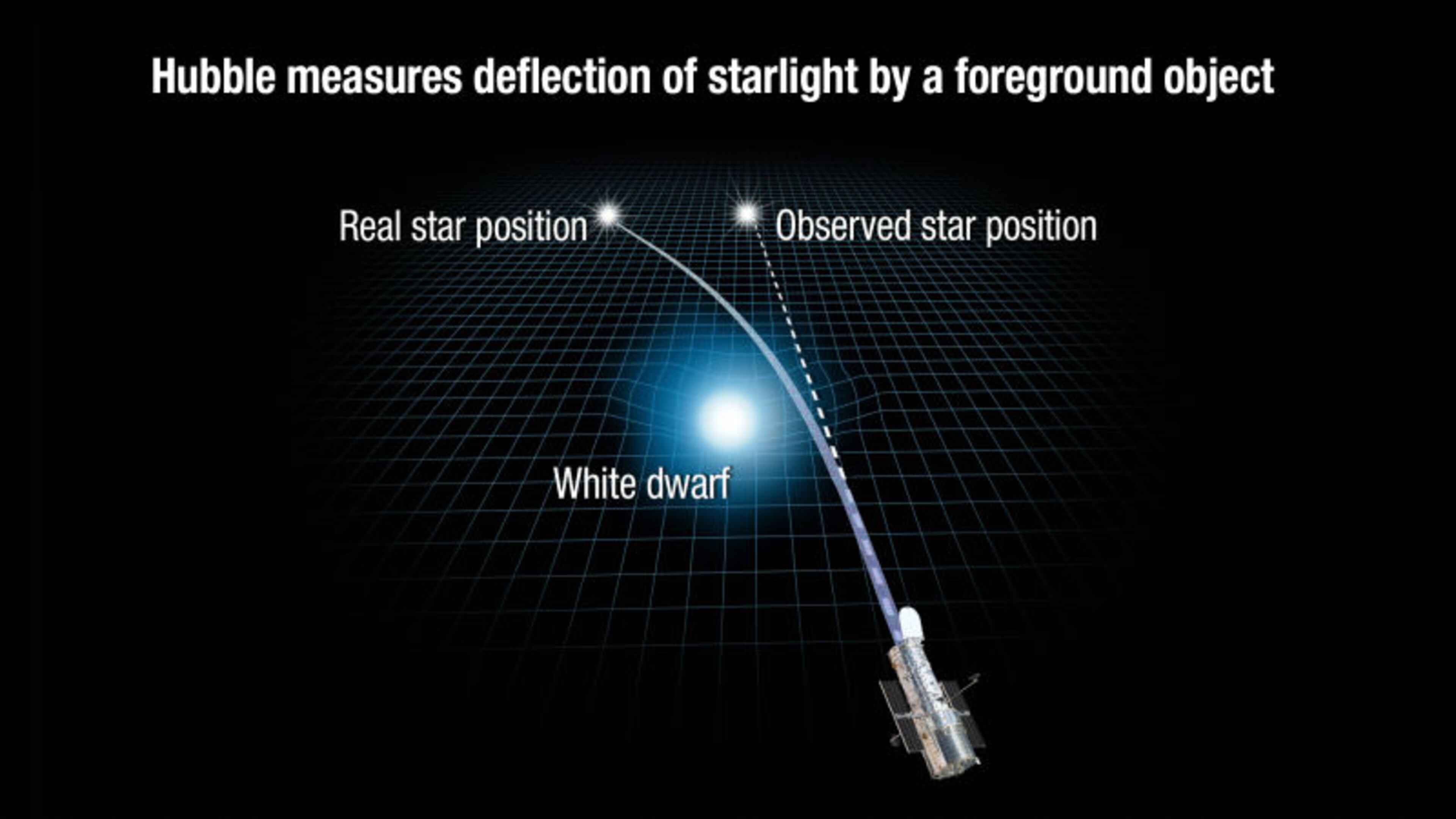

According to Gizmodo, they measured shifts in light as Stein 2051B passed in front of light sources behind it and behind other random stars, gathered the data and used Einstein's lensing equation to determine the star's mass.

After the two year study period, the team ultimately found that during close alignment, the distant light was offset by about 2 milliarcseconds from its actual position. According to NASA, that indicates a mass 86 percent that of the sun.

While researchers have measured the mass of white dwarf stars in the past using other theoretical models and binary systems, this is arguably the most model-independent mass measurement for a star, astronomer Pier-Emmanuel Tremblay from the University of Warwick told Gizmodo.

» RELATED: How Georgians can watch the rare total solar eclipse this summer

In 1919, during a solar eclipse, researchers discovered proof of Einstein's general theory of relativity as they observed the Sun's gravitational field pushing starlight over and around it.

Aside from the Sun, this phenomenon of gravitational microlensing has never been used to measure another star, until now.

But measuring the star through Einstein’s microlensing phenomenon is no easy feat.

» RELATED: Amazing photos from Hubble Space Telescope

"It's like if you put a firefly crossing the surface of a US quarter next to a light bulb in New York, and try to measure the motion of the firefly across that quarter... from Kansas City," Sahu told Gizmodo.

While the discovery is something scientists are proud of, most warn that repeated measurements and experiments are necessary to ensure this method of measuring stars is applicable to future research.

The findings from Sohu and his team will be published in “Science” on Friday, June 9.