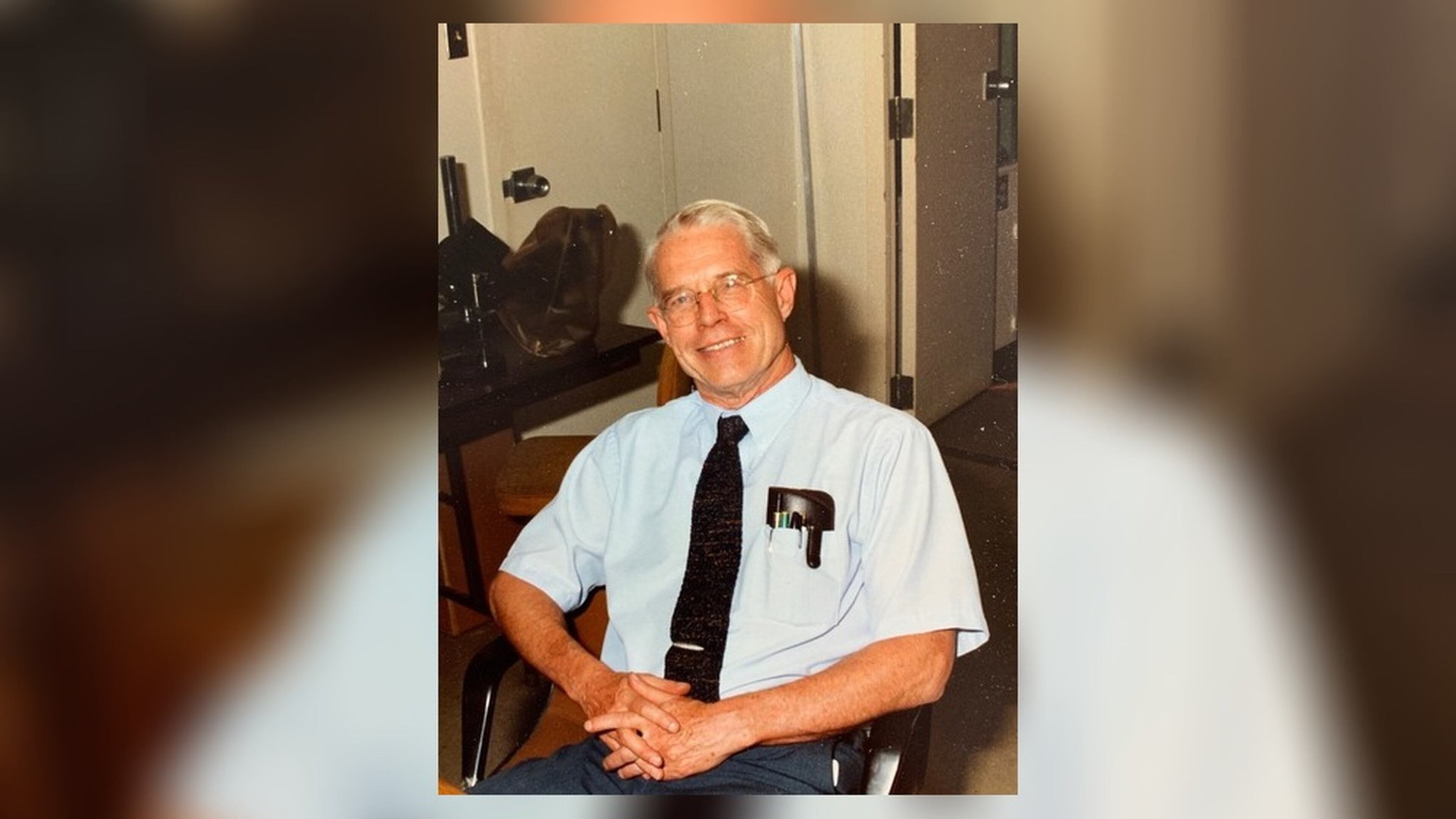

Larry Howard, who helped solve Atlanta Child Murders, dies at 91

Elaine Howard was stunned.

Opening up the refrigerator in her metro Atlanta home one night in 1956, she discovered something ghastly tucked in next to the baby bottles — a human foot clad in a sandal.

Turns out her husband, longtime forensic crime investigator Larry “Doc” Howard, had come back from a Hawkinsville case where a woman’s foot was blown off by a husband who suspected her of having an affair. Arriving home late, Howard stashed the evidence in the family cooler until he could take it into work.

“My mom raised hell about it,” said daughter Laure Kenyon. “They disagreed for years over whether he should have his own refrigerator. “

The incident came at the outset of Howard’s more than 30 years that saw him move to assistant director then director of the state crime lab, during which associates said he developed a towering reputation in forensic sciences. He was a formidable but humble man who handled death cases compassionately but in no-nonsense terms.

“For him, it was all about solving the puzzle,” said Kenyon. “He believed in the law and the science and the evidence, and he wouldn’t let anything sway him.” That, coupled with what granddaughter Sierra Kenyon called an “unrelenting curiosity about the world,” earned him the respect and friendship of law enforcers and prosecution and defense attorneys statewide.

Howard died at age 91 in Colorado Springs Jan. 3. He’s survived by his wife of more than 60 years, a sister, four children and a half-dozen grandkids. A celebration of his life is set from 3 to 6 p.m. Feb. 22 at the Cheyenne Mountain Resort in Colorado Springs.

Retired GBI director Vernon Keenan said Howard worked during an era when the crime lab delegated only him and one other investigator to do forensic work on cases across Georgia. Keenan said Howard’s penchant for pursuing the truth brooked no obstacles.

Witness the time when engine trouble forced him to emergency-land the Mooney light plane he flew to grass strips and small airports across the state for his work. He put it down on busy I-75. Undaunted, Howard called home to reassure his family, then hopped into a state trooper’s car to complete his journey.

In another instance, Howard was forced into an unusual work site in the case of an escaped prison inmate believed to have committed suicide. Security consultant Brad Bonnell, at the time a GBI agent, said the funeral home where Howard would have done an autopsy refused to accept the body because of its advanced state of decomposition.

“He got ahold of two 55-gallon drums and a sheet of plywood,” Keenan said, set it up outside the Catoosa County Animal Shelter and did it there.

Keenan said the solid, if occasionally unorthodox body of work Howard turned in marked him as “absolutely brilliant.”

Howard shunned the spotlight was but forced into the goldfish bowl in a number of high-profile crimes, including the cases known as the Atlanta Child Murders that played out in national news from 1979-81. He and his experts examined rug fiber evidence which, along with dog hair and blood, proved instrumental in the conviction of Wayne Williams in two cases. As the fiber evidence mounted prosecutors attributed the other 22 to Williams as well and closed the books.

The decision stirred controversy, but Howard told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution later the more the fibers were examined, the more it became impossible to attribute the murders to anyone else. “Some people didn’t want to believe that. Some still don’t,” he said.

His testimony in the Savannah murder case that inspired the book and movie “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil” was duly noted by the book’s author.

Howard’s thirst for knowledge was extensive. The Montana native arrived in Atlanta with a PhD in pharmacology from the University of Minnesota, then supplemented it with post-doctoral work in pathology and other medical disciplines at Emory. His boss trained him in forensics. On a whim, a question about the type of dirt on boots brought in from a crime scene started him down the road to a 1983 geology degree from Georgia State.

Despite high-toned academic chops, Howard was lauded as a master at boiling down complicated evidentiary science into language that juries could understand. And Bonnell said that those sitting in with him on an autopsy were treated to a running commentary on what he was finding and why.

“He was constantly teaching you, because he knew that you were going to be the investigator,” said Bonnell. “He wanted to impart what to look for.”

Howard retired in 1988, later accepting a position creating and running a new forensics lab in Colorado Springs and leaving behind a slew of accomplishments and accolades ranging from President of the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors to being named Man of the Year by the District Attorneys Association of Georgia in 1981.

But perhaps the ultimate tribute to his dedication and fair-mindedness comes from daughter Laure, who noted that sometimes his testimony could ruffle the feathers of both law enforcement and crime victims’ families-particularly in regards to racially charged cases.

“He pissed off people on both sides,” she said. “He’d go to court and say exactly what happened. This is what the science shows.”