When I last saw Mister K, he was in full-blown worry mode, which is how the hard-nosed, Philly-born overachiever rolls.

It was April 2012 and he faced a room of graduating high school seniors in Greene County, 75 miles east of Atlanta. His motto of “no excuses” had been drilled into them for 12 years. But senioritis had set in.

“You guys have sacrificed for years; I understand it,” Tom Kelly, AKA Mr. K, told the class. “Now you have to finish it.”

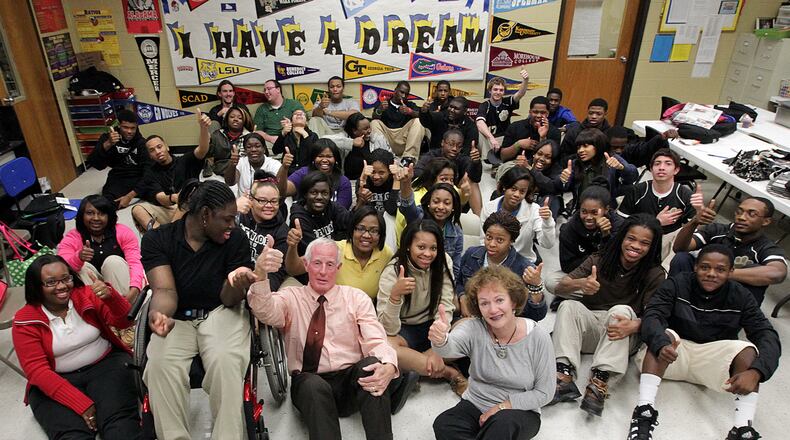

These were the Greensboro Dreamers, a group of kindergartners who Kelly, a retired healthcare CEO who was new to the area, promised to send to college if they graduated high school. In all, 45 walked the stage.

Now, four years later, they are finishing. Kelly and his wife, Kathy, are criss-crossing Georgia trying to attend as many graduations as possible. This week and last, 10 Dreamers are receiving bachelors degrees and four are getting associates.

Previously, 10 others earned associates or technical diplomas.

Among the recent grads are: the son of immigrants joining the Marines with the goal to be a pilot, a former foster child who wants to counsel kids like her, a nurse in the making and a future prison psychologist.

It’s come full circle; they’ve absorbed what Kelly has extolled for 16 years: Be confident and give back. That, of course, is on top of exhortations to sit up straight, look people in the eye, wake up early, be disciplined, own your mistakes. And dream.

“Where I am today has a lot to do with the Kellys,” said Kadijah Woods, the former foster kid who graduated from Georgia Southern. “People kind of gave up on me or didn’t expect a lot from me. I think I knew early on Mr. K wouldn’t give up.”

It wasn’t always rosy.

“It was harder because he’s older and a different race and you hear other things from the environment,” Woods said. “But he was always there and slowly, it sank in.”

Kelly is finally sighing some relief. That is after years of raising money, arm-wrestling sometimes recalcitrant school officials, tip-toeing around internal family dynamics and being the disciplinarian when kids screwed up and needed to learn there were consequences. It continued in college with homesickness (many wanted to quit after the first semester), roommate woes, enrollment snafus and the million other college-related issues.

Sure, the Kellys have wondered — often — “How did we ever get into this?” But they knew there was no going back.

To help bring focus and sanity to the program, Kelly hired a young educator, Beth Thomas, who for the past 16 years has been teacher/surrogate mother to the Dreamers, as well as good cop to Kelly’s bad cop.

It started in 2000, when 54 kids had their names plucked from a hat. Of those, nine moved away and nine left the program; nine others later joined.

The program gave them ice cream as rewards when they were young, flooded them with tutoring, taught them how to behave in tablecloth restaurants and even flew them to faraway cities. It was the first time most were ever on a plane. “You can’t dream unless you know what’s out there,” Kelly said.

The program raised nearly $3 million in donations (much of it from the Kellys), grants and money from fund-raisers. The program also brought in nearly $4 million in federal grants over a decade for after-school programs for the non-Dreamers at Greene County schools.

By next year, Kelly hopes that 14 more will receive bachelor’s degrees and a couple more achieve associate’s.

That would mean out of the 45 who graduated high school, about 40 may end up with some sort of diploma, which would be wildly successful for a district where dropout rates were high, test scores low and parental involvement spotty.

Jacayla Edwards just graduated from Georgia Southern and wants to be a nurse. She said leaving college without a degree “was not an option,” even after having a baby boy. She had to double down on work. That, too, happened with Kadijah Woods, who has a baby girl.

Interestingly, they were among the first Dreamers to have babies and also in the first group to finish college in four years.

Edwards said she was driven.

“I know there’s something out there for me,” she said. “Greensboro didn’t even have a Walmart. There’s really nothing there but fast food jobs.”

A trip home in the winter after the first semester in 2012 solved a lot of homesickness. The town wasn’t what the students had fondly remembered. Now many, if not most, aim to move on.

“We’re from a small town; it’s hard to get out unless you have someone pushing you,” said Kennedy Crutchfield, a Georgia State honors grad who wants to work helping prisoners.

During the recent graduations, the Kellys and Beth Thomas sat amid excited relatives, some of whom had never had a college grad in the family.

And now the journey is almost over. Edwards said Kelly “has had a harder time detaching himself. He still sees us as kids in high school.”

Then she added with a laugh, “I love that he feels that way.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured