Bill Torpy at Large: Chamblee is the lifeboat; DeKalb is the storm

A few years ago, Chamblee was a running punchline, a blue-collar burg with an Asian flavor, likely to get publicity only when radio host Neal Boortz called it “Chambodia.”

But now it’s a desirable location, a lifeboat for the wandering tribe of Lakeside, who are certainly a resilient and determined bunch.

Two years ago, a group of residents in north-central DeKalb County tried to create the city of Lakeside. They made lots of enemies and got shot down in the Legislature.

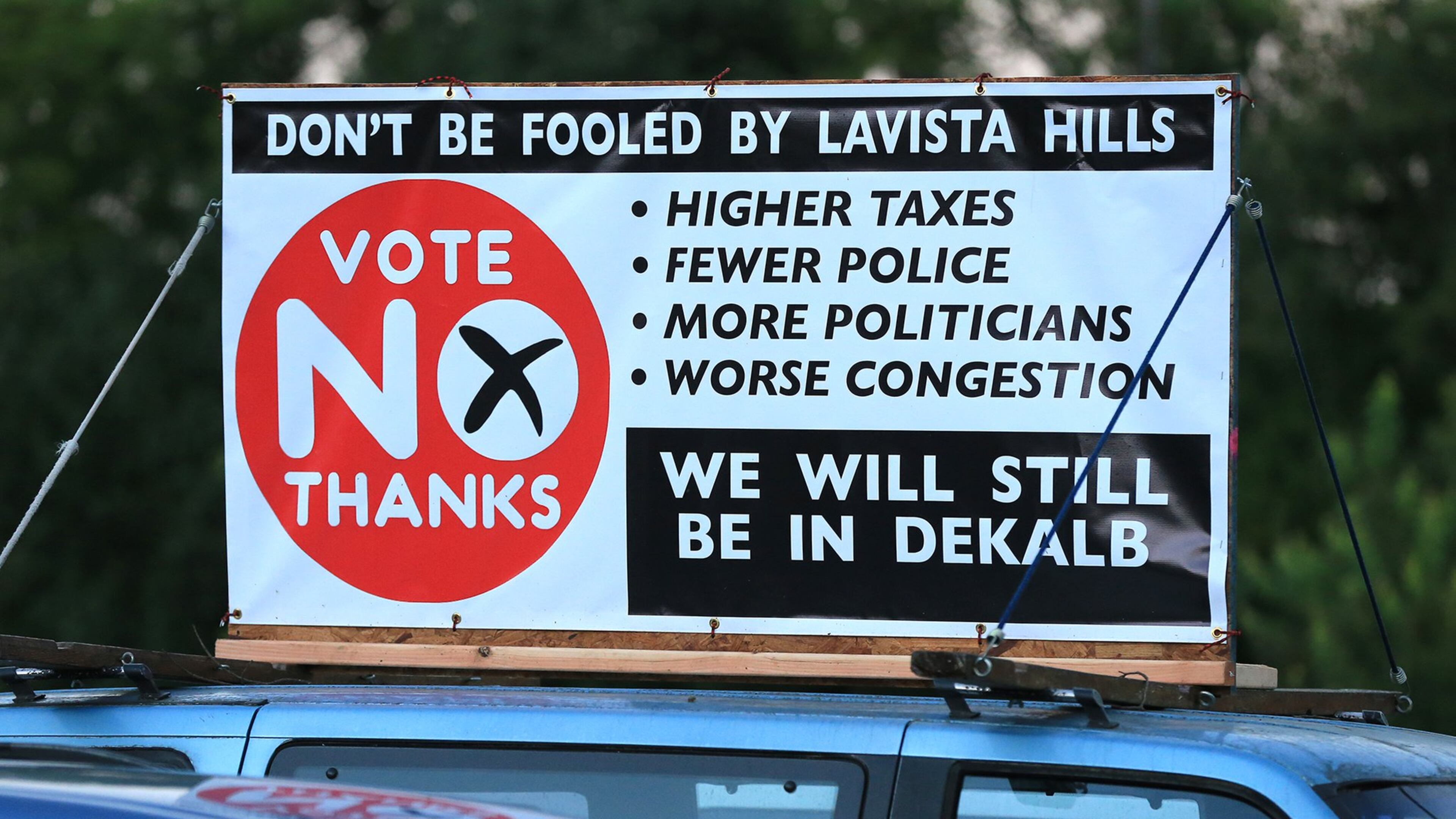

Last year, they rebranded themselves as LaVista Hills, drew in some Democrats to soften their image in the largely left-leaning area, but still got beat narrowly in a referendum.

Now, they’re back. This time a group in the northeast half of what would have become LaVista Hills — the section that voted to citify — is now practically begging to join Chamblee.

Admittedly, it’s an odd concoction: The LaVista area that is hoping to get annexed by Chamblee is bigger than the city itself. In all, there are 35,000 newcomers to just 29,000 Chambleedians.

That fact has gotten many longtime Chamblee residents very wary. Those LaVista folks might seem nice and polite right now when they’re trying to get in, but once you let them aboard … Bam! Then they have the numbers to run the whole shebang.

Think it’s your city? Think again.

“It would essentially hand over political control of the city to the new people moving in,” said Lee Floyd, a former city councilman. “They want out of DeKalb County and don’t care who they run over to get it.”

Floyd is referring to the headlong race by communities in unincorporated DeKalb to set up municipal firewalls against the corruption and dysfunction that has accompanied county government in recent years.

And to make matters worse, Floyd said, current Chamblee residents don’t have a vote in the annexation. It’s up to the City Council to pass a resolution and then state lawmakers to pass legislation that would allow the LaVista area to vote in a referendum. Chamblee residents could be spectators to the whole process.

The LaVista folks are clamoring for the matter to come about quickly. They argue Chamblee must quickly annex them or the new city of Tucker will annex Northlake Mall and valuable commercial area around it. If that happens, then all this is not worth Chamblee’s bother.

The ironic thing, I must note, is Tucker became a city in the first place to stave off incursions by the Lakeside/LaVista Crowd.

Getting the matter passed in these rushed and waning days of the Legislature would be hard to do, said state Sen. Fran Millar, a Republican from Dunwoody who never met a new city he didn’t like. But stranger things have happened in legislative circles.

It’s been tough to get a read on what city officials want. “They’re giving us the rope-a-dope,” Floyd complained, bringing to mind an image of Mayor Eric Clarkson, covering up with boxing gloves in front of his face as constituents pound at his body.

When running for office 10 years ago, Clarkson was “too pro-development, too much of a yuppie for the workingclass town,” according to critics quoted in an AJC story.

The mayor, a silver-tongued salesman, is ambitious for Chamblee to become a regional player and the city has grown from 9,800 residents in 2010 to 29,000 now through a couple of large annexations. The population is nearly half Hispanic, although the council and almost all those at the meetings are white.

On Feb. 8 Chamblee officials held a town hall meeting to explore the massive annexation idea, which seemed to surface from nowhere. The effort, to many, seemed to get a mayoral wave of approval when Clarkson said, “I’m in support of exploring it further because if a group of people think enough of us, and want to be a part of it, then we ought to give them an opportunity to vote for it.”

Later, he noted there was a “sense of urgency.”

At a meeting a week later, Councilman Tom Hogan noted large projects like the downtown redevelopment project would be a lot easier if funding was spread out among all the civic newbies. Hogan said he was seeking resident approval and positive financial studies. He also noted that Chamblee would gain political clout if it grew to 65,000 residents, allowing it to elbow its way to the table with new neighbors like Dunwoody and Brookhaven.

For a long time Chamblee hasn’t even been an afterthought; it’s not a thought at all.

At that meeting, Dan Schafstall, a Chamblee aspirant, approached the council noting that he feels hostility for the newcomers.

“We’re not the enemy trying to invade; that’s not me,” he said. “I try to get involved. I clean the street I live on. I’m just a person who wants what all these good citizens have.”

That a tax-paying citizen has to sound like a refugee trying to talk his way through a border crossing is the shame that DeKalb County has become.

Communities look upon others cautiously, like they’re worried the others will steal their flat-screen TVs. Neighbors have turned on each other in divisive annexation discussions and cityhood movements. Communities grab whatever commercial property they can and damn those left behind.

In DeKalb it’s every man for himself.