With little prompting any graduate of Morehouse College will recite for you the following: “You can always tell a Morehouse Man. But you can’t tell him much.”

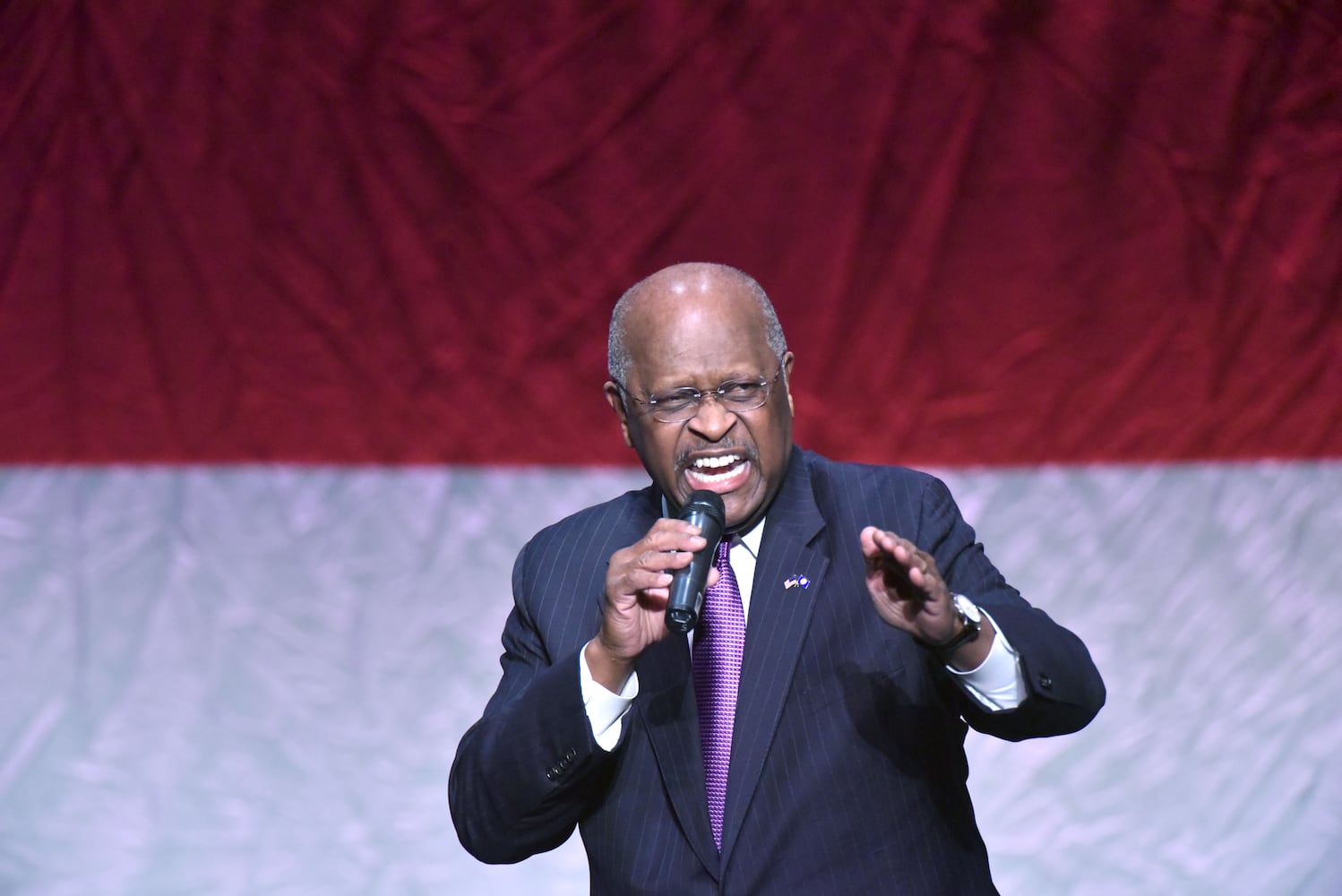

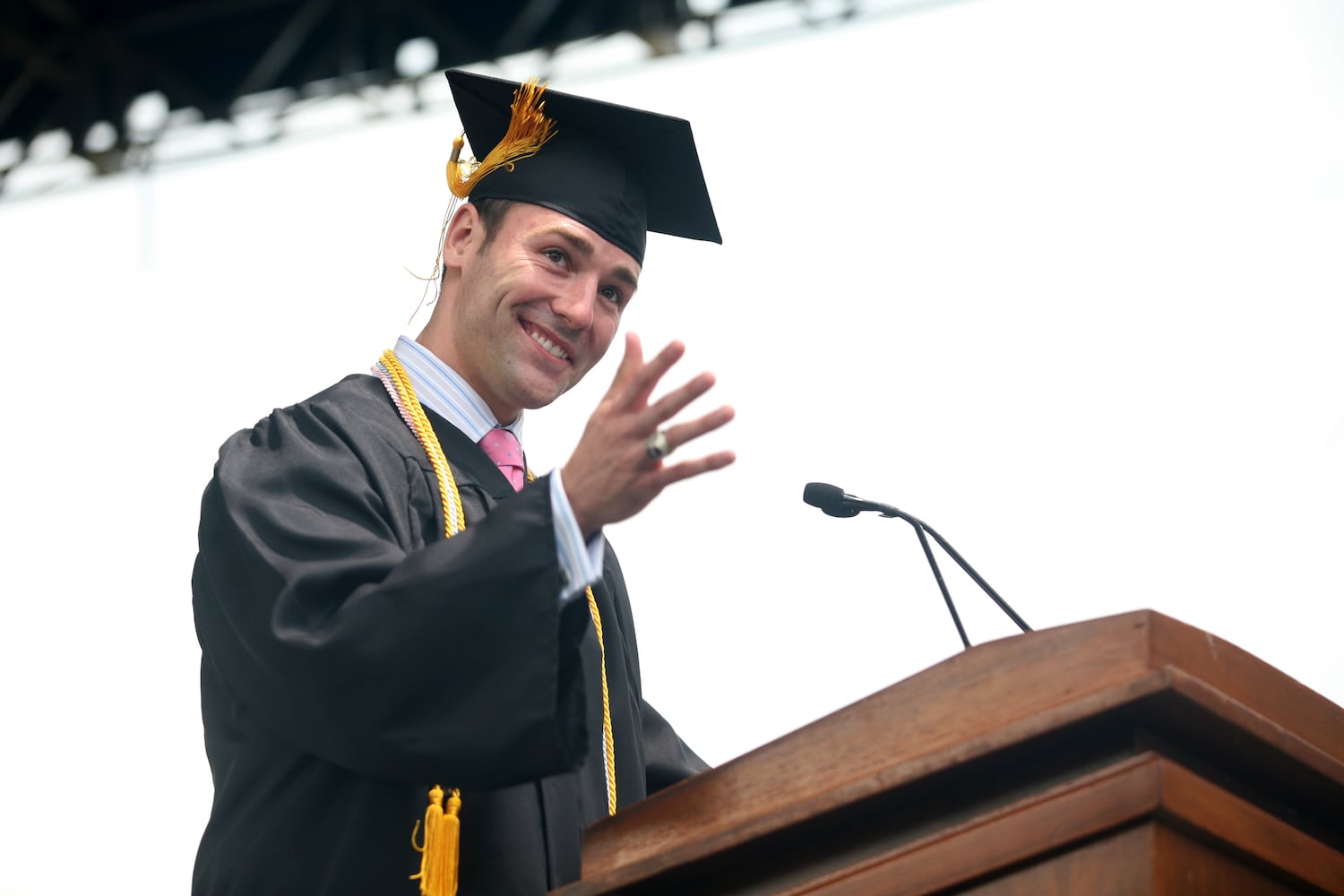

Enter Herman Cain, Morehouse Class of ‘67 and a front-runner to become the Republican nominee for president, according to recent polling.

In debates Cain has behaved in a manner true to the Morehouse man's reputation, quickly rebutting challenges accusing his rivals of being flat wrong and exerting a plain-spoken and commanding style that is winning him fans nationwide.

But historically black and all-male Morehouse, while proud of Cain's accomplishments, is also divided about his presidential bid.

Some students, alumni and faculty of the private Atlanta college say Cain’s conservative views do not mesh with the values taught at Morehouse. Others say Cain epitomizes Morehouse.

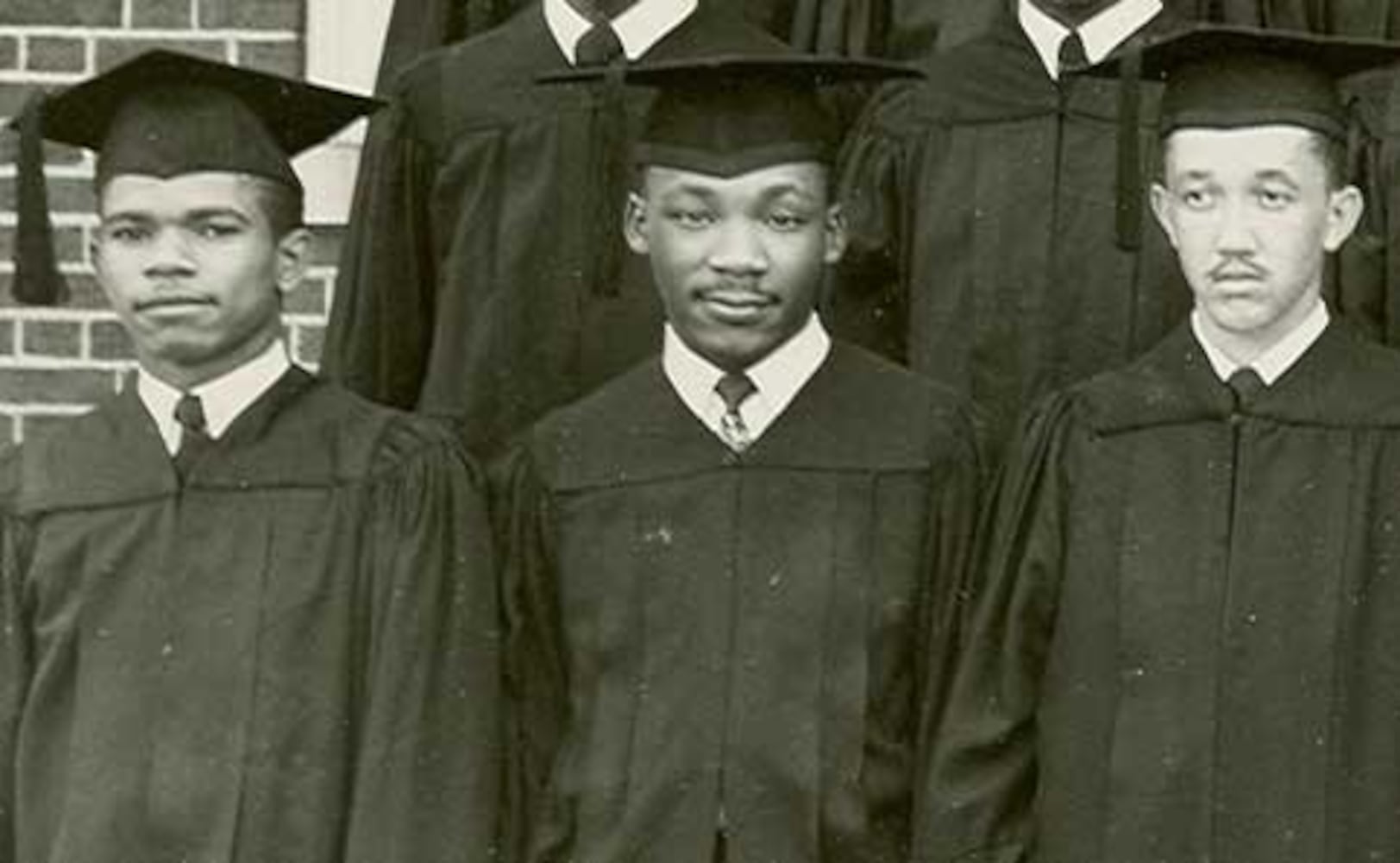

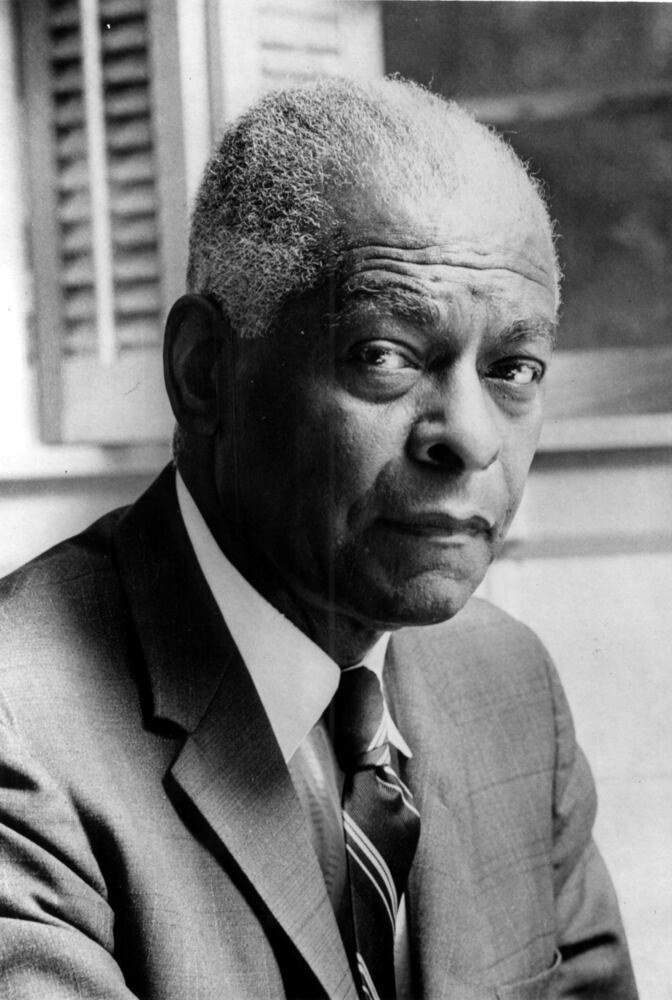

“The politics that he has embraced does not represent the likes of Mordecai Wyatt Johnson, Benjamin Mays, Martin Luther King Jr., Maynard Jackson and Howard Thurman,” said 1964 graduate Amos Brown, comparing Cain to some of Morehouse's most accomplished alums. “We acknowledge what he has done as a business person, but we don’t take pride in [Cain's candidacy], we don’t crow in it. We came up with certain traditions. Herman Cain did not.”

But Marcellus Barksdale, chairman of Morehouse’s African-American Studies Department, argues that Cain is exactly what a Morehouse Man should represent.

Cain is a millionaire businessman, having served as CEO of Godfather’s Pizza and a member of the Federal Reserve Bank. He is also a life member of the National Alumni Association and a former member of Morehouse’s board of trustees.

“I may not believe in his politics, but he has done what we have been taught to do,” said Barksdale, a 1965 Morehouse graduate. “ He has had a wonderful career... He has the right to run for president and I respect his run.”

Although he overlapped Cain for three years as students, Michael Lomax, president of the United Negro College Fund, said he doesn’t know. But when he watches him on television and debates, and even in studying his business accomplishments, he sees familiar tropes.

“The elements of what you see in Herman Cain today were seeds planted, developed and nurtured at Morehouse,” said Lomax, a 1968 graduate. “He is vintage Morehouse, as far as I am concerned. Strong personality. Forceful. Engaging. A supercharged ego. ... Those are all elements of Morehouse. "

A Cain nomination would pit him against President Obama, the nation's first black president and a Democrat who earned 96 percent of black votes in 2008. Obama, suffering from historically low job approval ratings in a still sluggish economy, will likely need every one of those votes to earn re-election. Putting Cain on the Republican ticket, even as vice president, could put some black votes in play.

Morehouse College Republicans think black voters should easily identify with Cain.

“So often we're given this media stereotype of a black Republican as someone who is outside mainstream black America, but Cain's run does away with all these stereotypes" said De'Von Weatherspoon, a member of the Morehouse College Republicans. "He was born in the South, went to Mother Morehouse, had a successful career in business, and is still very much so connected to Black America.”

When Cain walked on to the Morehouse campus as a freshman in the fall of 1963, he entered a bubble close to, but far away from, his poor upbringing in West Atlanta. There were fewer than 1,000 students on a campus ruled by President Benjamin Mays.

The civil rights movement was in full swing and Morehouse Men by the dozen were joining the cause. But it was also a time when a sharp graduate from the only black college in the country for men, could start thinking seriously about joining the white corporate world.

Cain did not respond to interview requests from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution to talk about his Morehouse days. In his book, “This Is Herman Cain: My Journey to the White House,” Cain said he enrolled in Morehouse after getting rejected by both the University of Georgia and Georgia Tech.

“When I enrolled I had no idea of its great reputation as an institution of high learning,” Cain wrote, adding that he was a math major given a scholarship his freshman year, but lost it because he couldn’t maintain a B average.

It is unclear exactly how significant a role Morehouse played in Cain’s life, as he dedicated only five pages in his book to his four years there. But according to those who knew him, Cain blended in , but was never a leader on campus.

He was a baritone bass in the Glee Club, which according to Barksdale, was one of the most important student groups on campus, represented by a cross section of students who would tour the North to recruit and raise money for the school. Cain was a good enough singer to make the 39-member touring group.

“He was well-liked, but not that involved in student affairs,” Barksdale said.

Lomax said Morehouse was rather isolated in those days and students rarely ventured beyond the campus. If they went to Buckhead or Midtown, it was to work – mostly waiting tables.

Students would leave campus whenever King came calling.

“If you were a student at Morehouse from ‘64-'68, when Martin Luther King came on campus and said I want you to march downtown with me, we did it, because that was the call,” Lomax said. “Ninety-nine percent of the students stood foursquare with Dr. King. On campus, you were being prepared for what the school assumed was inevitable, which was integration.”

Cain wrote in his book that he never marched and followed Jim Crow law to obey his father's rule to "stay out of trouble," which he did.

“A lot of these students, at some point, were hoping to break into corporate America,” Lomax said. “Cain found his niche. His conservative business values got channeled into something that was very nascent at Morehouse, an entrepreneurial ambition to get out there and run your own business and make a lot of money.”

Brown, a 1964 graduate and pastor of Third Baptist Church of San Francisco, said that is part of his issue with Cain, who sat on the sidelines during the height of the civil rights movement as his Morehouse classmates put themselves at risk.

“We do respect him as a person. But in terms of his politics, his analysis of what is happening in this country, you would not find any thinking Morehouse man who would embrace his position,” Brown said.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured