After months of avoiding public scrutiny, organizers of an East Cobb incorporation effort finally met with people who would be residents of the new city — and it didn’t go well.

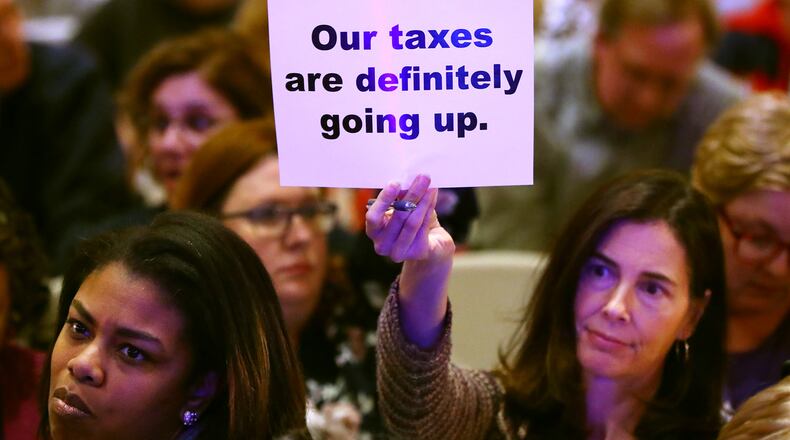

The lone advocate from the group pushing the new city faced a barrage of tough questions at a tense town hall of several hundred people at the Catholic Church of St. Ann on Thursday.

There were doubts about why a new city was needed and questions about the impact another layer of government would have on local taxpayers. Some were also vexed by the secrecy of the group pushing cityhood, which has repeatedly declined to disclose its membership or funding even as it hired a public relations consultant and a lobbyist.

David Birdwell, an East Cobb businessman who represents the group pushing the initiative, offered few satisfying answers to a crowd skeptical about why East Cobb should join the cityhood movement that has reshaped local politics across the metro area for more than a decade.

Birdwell said a new city would not increase taxes or affect schools. It would, he said, improve public safety, zoning and “local representation.”

“We think it has enough merit to explore it,” Birdwell said. “It’s all about preserving and enhancing what we’ve got in East Cobb.”

The town hall, which was the first public forum to discus a proposed city, was organized by Commissioner Bob Ott, who has not taken a position on the issue. Proponents are poised to begin the two-year legislative process of making the city a reality, and the frustration among some residents in attendance was palpable.

“Why is there a rush to make it in this General Assembly?” one woman asked and was met with loud cheers from the audience.

The proposed city of East Cobb would be home to 97,000 residents north of Cumberland and east of Marietta to the Fulton County Line, making it Cobb’s largest city and its first in more than 100 years.

State Rep. Matt Dollar, R-Marietta, has announced his intention to sponsor cityhood legislation this session, which ends next week. The bill would have to pass next year in order to hold a referendum in 2020 as supporters are hoping.

At least ten new cities have incorporated since Sandy Springs established its independence in 2005. Several more were defeated at the ballot box, including, most recently, Eagles Landing, in Henry County, which ignited controversy over racial and economic divisions in the community.

On Thursday, some East Cobb residents who spoke at the town hall expressed skepticism about the cityhood proponents’ true motives and the way they rolled out the proposal. One woman held a sign that read: “Covert: Concealed; secret; disguised.”

“What I’m missing is information about why we’re doing this,” one man said. “I don’t see any data that says how [public safety, zoning and representation] are currently inadequate.”

Another woman pointed to social media comments by one of the movement's few public backers suggesting East Cobb needed to incorporate to stave off a Democratic takeover of the county.

“That’s not a reason to do this!” she said to cheers.

Others questioned the validity of the Georgia State feasibility study commissioned on behalf of the new city that concluded it could be funded using just the small portion of tax dollars that residents currently pay toward the county’s fire fund.

Three of Cobb’s six existing cities fund their own fire departments, and three rely on the county and pay into its fire fund. Any new city would have to reach an intergovernmental agreement with the county on services Cobb would be expected to provide, including libraries, parks and road maintenance, which could change or drive up the projected cost.

“With these things, the devil is in the details,” said Kerwin Swint, a political scientist at Kennesaw State University. “It’s going to be hard to overcome the skepticism, especially with Cobb County taxpayers who tend to be very cautious and conservative.”

Speaking after the event, several residents said they were leaving with as many questions as they brought.

“I don’t think they have enough information,” said Christine McKinnell, a real estate agent.

She said that while there’s “always room for improvement” in services, “I don’t think there’s a real specific reason” to incorporate.

Tonya Grimmke, a teacher with the Cobb County school system, said she was concerned about East Cobb trying to insulate itself from demographic and political changes.

“It seems to me that it’s pretty transparent, especially when you’ve got the guy making the presentation saying that they want to preserve the East Cobb way of life,” Grimmke said. “That’s pretty much a dog whistle to me. They don’t want those people in their area, the same reason they don’t want transit in East Cobb.”

East Cobb political activist Larry Savage, who has run unsuccessfully twice for county commission chair, called the reaction a learning experience for cityhood representatives.

“I think they may have been surprised that people weren’t quite as willing to embrace as expected,” he said. “I don’t think they yet understand the finances.”

But not everyone was put off by the presentation.

David Conrad, a commercial real estate broker, said it was a good start and urged patience over “knee-jerk opinions” from his neighbors.

“Everybody gets to vote on it,” Conrad said. “I don’t see how anybody could object to a good democratic process.”

As for Birdwell, he said it went “as expected.” He lamented that the partisan comments by Phil Kent, the conservative commentator who has been acting as the group’s spokesman and warned of “Democrat control” of the county, “have gotten attached to us.” He said Kent was no longer acting as the public face of the movement but was still being paid as a consultant.

“We’ve got a big job to do” with outreach and engagement, he acknowledged.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured