Shooting raises questions about school safety in metro Atlanta

The morning after 17 people were shot and killed inside a Florida high school, Frances Greene was driving her grandson to school when she said he asked a question.

“Will it happen at my school, Nana?,” the boy, a seventh-grader at Gwinnett County’s Moore Middle School, wondered.

Will it happen at my school? Are schools and law enforcement doing enough to prevent such tragedies? What do schools do when they think someone may be a threat to students and faculty?

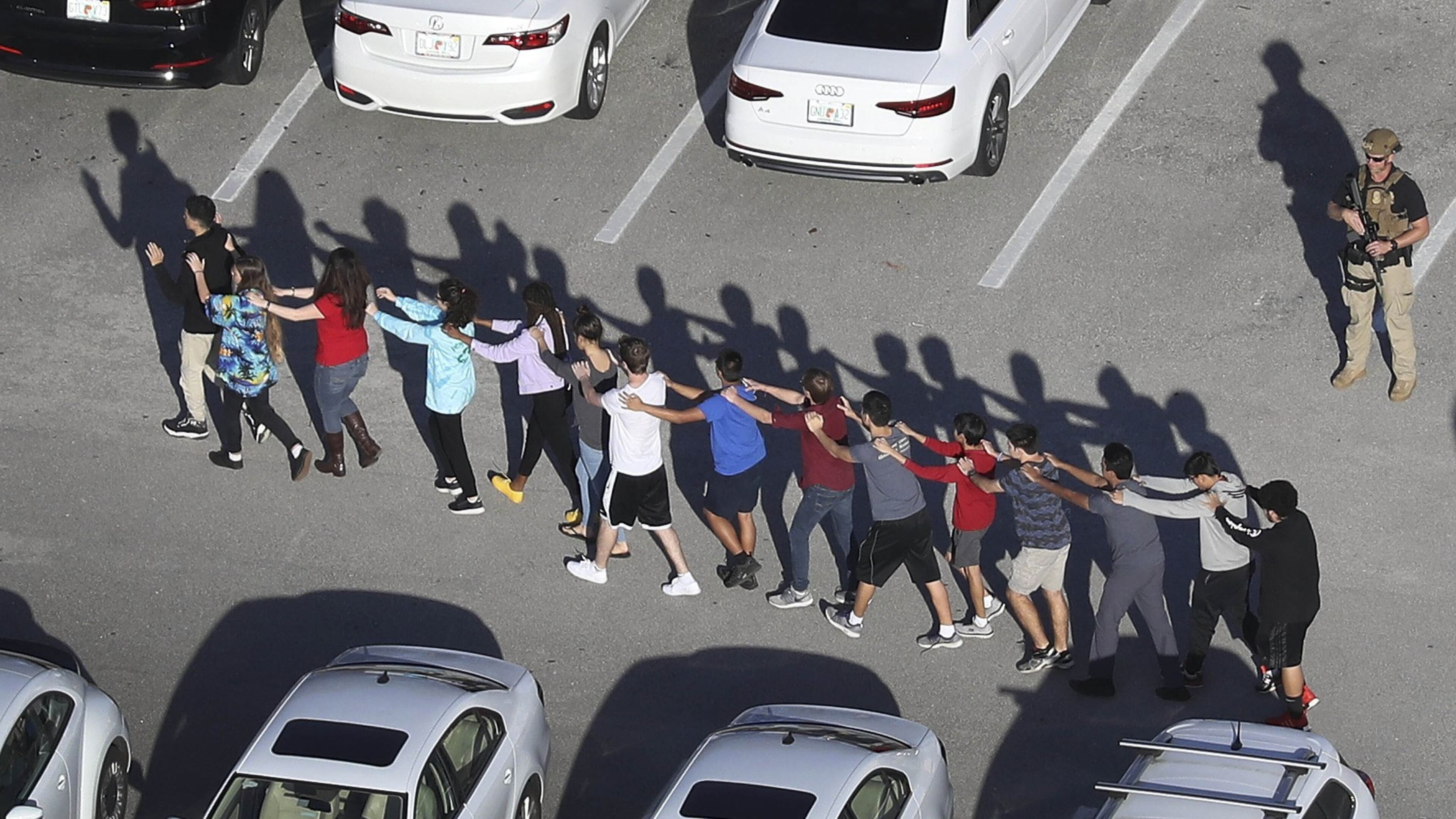

These are questions being asked throughout the region and the nation as school shootings sadly become commonplace. Wednesday's killings at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Broward County were the deadliest at a school since December 2012 when 20 students and six teachers were killed at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn.

Local schools have put more armed officers in buildings and installed intercom systems that require anyone to be buzzed inside a school after classes start. They monitor social media for signs of trouble and hold active shooter drills. Universities such as Georgia State and Kennesaw State have launched the LiveSafe app, which provides students and staff a direct connection to campus police to communicate their safety needs.

Metro Atlanta’s public schools and colleges have avoided such tragedies, but many parents and educators say schools can do more, such as hiring more counselors to assist troubled students. Although many schools have more officers, some wonder if the increased security is enough. Many campuses consist of multiple buildings and many also have separate trailer classrooms scattered in parking lots. Often, there is one officer to patrol the property.

As Greene's grandson wondered about his school, hours later, in another part of Gwinnett, Lanier High School officials announced a student brought a gun to school. The number of disciplinary incidents involving handguns in Georgia's public schools has increased from 76 during the 2014-15 school year to 149 last school year, state data shows.

“The schools take a lot of this too lightly,” said Greene.

Greene has her own questions for her grandson, which have nothing to do with schoolwork.

“You have to ask ‘Are you happy at school?’ ‘Is anybody picking on you?,’ ” she said. “It’s a shame you have to ask these questions. And many students, particularly boys, don’t want to tell.”

And that is a crack in the last line of school defenses — students.

‘You do the best you can’

School officials say the area they need the most help with is spotting potential trouble, particularly on social media. Federal authorities conceded Friday they missed the warning signs in Florida.

The alleged shooter, Nikolas Cruz, 19, had been expelled from the school, officials said. He posted several photos of himself with guns and messages threatening violence at a school. Authorities said he came to the school Wednesday afternoon, armed with his AR-15 rifle, a gas mask, smoke grenades and multiple magazines of ammunition, and he opened fire.

Under Georgia law, a buyer must be 21 to get a handgun permit, unless the person is at least 18 and has been honorably discharged from the military. A licensed gun dealer can sell a long gun such as a rifle to anyone 18 or older, but there is no minimum age for possessing one, if it were purchased by an adult.

Increased school safety became a critical concern after the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado that claimed the lives of 12 students and a teacher.

Georgia has had several near tragedies in recent years, such as two Cherokee County teenagers who were charged in October with plotting to use a homemade explosive device to kill students and staff at Etowah High School. But a tipster let police know one of the two had posted something suspicious online, and both are now in jail facing serious charges.

School districts say they rely on students to share information they see online about students who may pose a threat. Increasingly, schools scramble to put additional officers on campuses where they hear about a threat, and schools send messages to parents. Lanier High principal Christopher Martin credited people for providing information that allowed the school to find the weapon Thursday, he wrote in a letter to parents.

Former school principal Bill Sloan said some schools, particularly those built before mass school shootings, are all but impossible to completely secure. By the time he retired in 2005, there were five detached buildings at East Hall High in Hall County. Students had to pass between the structures, so the doors remained unlocked. East Hall High did, at least, have an armed officer. But the officer couldn’t be in all five buildings at one time, Sloan said.

Mo Canady, executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers, is worried many school buildings are easy targets. He said there are about 100,000 school buildings in the country, and about 20,000 school resource officers. Most school shootings, he said, have occurred in buildings without an officer.

“That should tell us a school resource officer presence is important,” Canady said.

East Hall High has grown since Sloan’s retirement, adding two more wings.

“It’s an impossible situation to control,” said Sloan, who is now the executive director of the Georgia Retired Educators Association. “You can do the best you can and hope it doesn’t happen.”

Students still must pass between buildings, so when the bell rings, teachers rotate between 15 of the roughly 40 exterior doors, unlocking them to let students pass. If a student must move from one to the other between bells, then someone must be sent to open the doors.

“Sometimes it gets a little taxing,” said Jeff Cooper, the current principal. But he said safety is now “part of the culture.” Even so, no school building, or any building for that matter, can be completely secure, he said. “We are as secure as we can be.”

His superintendent, Will Schofield, said the school district has spent millions of dollars “locking down doors,” employing officers and installing safety cameras, but said he believes it’s impossible to prevent a mass shooting. All he can do is be the homeowner with the sturdiest door on the street. Schools can “create a climate and a culture that makes it more difficult,” he said.

Schofield said schools must do even more, but, he added, “I don’t think we want to turn our schools into prisons.”

Counselors, surveillance and vigilance

Antoinette Tuff, the former school bookkeeper who famously talked a gunman out of shooting up a DeKalb County school, said security remains an unsolved problem.

“We don’t know exactly how to handle that,” said Tuff, who left education and the Atlanta area and now lives in Dallas. Rather than focusing on guns, she’s focused on the shooter.

In 2013, she calmed the man who had entered Ronald E. McNair Discovery Learning Academy with an AK-47, firing at the ground. He essentially had her as a hostage inside the school. To Tuff, he seemed to be crying out for help.

Like Tuff, first-grade teacher Jack Brinson believes he's has a religious calling to help others. Brinson said it hasn't been easy. He left an elementary school in Clayton County two years ago after he felt threatened. He's now at Fulton County's Park Lane Elementary School.

Brinson, 55, also an assistant pastor, is old school. He remembers when school discipline largely consisted of corporal punishment and believes more of that, along with school prayer, would help teachers to regain control of classrooms. Brinson said he still hears tough talk from some students at his current school, but is committed to help them all.

“You are a Brinson for life,” he said he tells students.

Reaching troubled students, though, is difficult, Brinson said, because class sizes are too large and schools need more counselors. School officials says counselors are the first line of defense and help, guiding students through problems and recognizing students with troubles at school or home.

“These children bear a burden…and they’re yearning to explain what is going on on the inside, but they can’t put it in words,” said Joyce Morley, a DeKalb County Board of Education member and licensed psychotherapist. “So they begin to act out. No one has given them permission to say it’s OK to hurt.”

The American School Counselor Association recommends one counselor for every 250 students. Georgia is above the national average, according to the association’s research, with an average of one counselor for every 484 students.

Area schools are trying other ways to keep track of potential threats.

Atlanta Public Schools officials sometimes issue criminal trespass warnings to those who pose a threat. If district officials determine there is reason for continued concern, APS will follow up with students who have been expelled from school, she said.

Clayton County school leaders said Friday they’re considering adding an active shooter emergency app.

DeKalb County school officials say in the last year, they’ve included more personnel, cameras, metal detectors and its first-ever K-9 officers. One new elementary school has security gates made of heavy metal grating that can be rolled down to cut off access to hallways during an emergency. Superintendent Steve Green said it also partners with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation for matters involving individuals whose behavior needs to be watched. District officials also are doing additional surveillance through social media.

The best security measure, they said, remains the eyes and ears of others. Some who saw Cruz’s social media posts now say they wish they had raised the alarm about him.

“We’ve been working on instilling in the culture, if you see something, say something,” said Green.

“We can put all the cameras there. We can put all the K-9s. All that is supportive. But if you’ve got a culture where students and staff will report what they see, that is more helpful.”

Note: This article has been updated to correctly attribute a quote to Green.

Here are suggestions for some experts for students, parents and guardians to consider a school’s active shooter policy or similar emergency:

- Parents should inquire as to admittance procedures during school hours, number of training sessions and drills per school year and collaboration with local law enforcement.

- Students should remain quiet, still and alert if a shooter is inside the school.

- Close and lock the classroom door.

- Alert law enforcement before contacting parents or guardians.

Sources: National PTA; Pete Blair, executive director, ALERRT Center at Texas State University; Mo Canady, executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers.