Police trainers: We can’t prevent shootings, but can be ready

With two school-age daughters, another in day care and a wife who teaches in the Cobb County school system, Maj. Jake King says one of his worst nightmares is an active shooter in a school.

As an officer with the Marietta Police Department, he specializes in community outreach, and a big part of his job is training the community how to react to those nightmares. They were uncommon when he began his lifelong law enforcement career. Then, in April 1999, the site of a horrific moment in American history became a sad addition to our national vocabulary.

“Columbine changed how we approach active-shooter events,” he said. “It wasn’t the first one, but it was the most calculated, and the goals for the shooters (King refuses to give power to the act by uttering their names) was one thing: kill as many people as possible.

“We need to remember the heroes — the ones who sacrificed their lives to save others,” he said. “I will never glorify that kind of violence by commemorating the ones who did the killing.”

That’s a big part of the training he teaches.

Best option: Get away

He was part of a seminar last Monday at Marietta High School. There he showed 300 people — mostly teachers — how they can best save lives if someone comes to their school intent on mass murder.

Shortly after the Columbine tragedy, he received instruction on how to train other officers in the Civilian Response to Active Shooter Events course at the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training center at Texas State University.

While all types of training involve some form of getting away from the shooter, the manner varies. Getting away from the shooter by running away or “avoiding” the situation is ideal.

“Every time you enter a room, look for all the exits,” said King. “The way you came in isn’t always the best way to get out.”

But sometimes that is not an option.

Once you take getting away out of the equation, there are two basic schools of thought when encountering someone shooting people — hide or engage.

During Monday’s seminar, King pointed out some differences between hiding and what the CRASE training calls “denying.” He shared data from the mass shooting at Virginia Tech on April 17, 2007. In a classroom with 19 students who hid, all but one was shot and 12 were killed. In another classroom with 12 present, none were shot because the shooter wasn’t able to get into the room.

King pointed out several ways to keep a shooter from entering a room: barricade the door with furniture; use a belt or other materials to make it impossible to open a door that swings outward to the hall; cover windows and turn out lights so the classroom appears empty.

But when that’s not enough, King said teachers and students need to be ready to defend themselves.

Common items found in a classroom can become weapons in a pinch — scissors, disinfectant spray, fire extinguishers, for example.

“Denial is built into all of us,” said King. “We don’t want to believe these bad things will happen, odds are they won’t but we need to be ready if they do happen.”

Can’t prevent, can be prepared

After the shooting last month at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., many were concerned that training and safety drills weren’t enough to stop a gunman from killing 17 people.

Like most metro Atlanta schools, the Broward County, Fla., school system provided active-shooter training, and a law enforcement officer is assigned to every school. All schools have a single point of entry to control who enters the building.

But no amount of training will keep a school completely safe, said Curt Lavarello, executive director of the School Safety Advocacy Council.

“Each situation is different and if someone is determined enough, they will cause harm,” he said. “But the best you can do is be trained to save as many lives as possible.”

With 25-plus years in law enforcement as patrolman, detective, gang task force member, traffic cop and 18 years as a school resource officer, he developed and served as the director for the first youth/teen court program for Palm Beach County, Florida. The program gained national recognition and became one of the largest teen diversion programs in the nation. SSAC is one of the leading training organization for school districts and law enforcement agencies in the nation.

“We can’t sit back and wait for law enforcement to arrive,” said Lavarello. “Most incidents are over in 10 to 15 minutes and someone coming in has to assess the situation and that takes time.”

Across metro Atlanta, school districts are constantly re-evaluating their tactics to determine if there’s something new or better out there.

“We try to look at these incidents that have been occurring around the country to make sure that we are not missing something or need to change the way we handle active shooter situations or other threats,” said Gwinnett County Chief of Police Wayne Rikard. “Over the past few years, we have worked with Gwinnett County Police and other agencies to train and have hosted several active-shooter drills at our schools.”

Teachers were heroes

In a New York Times op-ed article last month, Carson Abt, a student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School praised the actions of school staff.

“My teachers are the light. Through a combination of training and determination, they calmed the fear of some and saved the lives of others,” she wrote. “When schools across the country lower their flags and share our darkness, they should also share our light. Maybe heroism can’t be taught, but preparedness certainly can be. Every teacher should have training for a school shooting like mine did.”

Local parents hope the courage and readiness shown by those instructors will be the same for teachers here.

Renell Byrd has a son at Grayson High School in Gwinnett County, and she said the school had a drill last week.

“The drill took place while he was in an outside portable,” she said, referring to a trailer used as a classroom. “He doesn’t feel comfortable about what’s going on, but what can you do?”

Mitch Leff, a Boy Scout leader and father of a sophomore and a senior at Lakeside in DeKalb County, said although his sons were involved in a lockdown Thursday, they’ve been pretty calm about the student who brought a gun to school recently and the school shootings in the news.

“It’s probably two-fold,” said Leff. “The school has been excellent about communication and we talk about what’s going on.”

While the topic may not be dinner conversation every day, Leff said scouting has helped him and his boys with situational awareness.

“There’s only so much anyone can do,” said Leff. “I feel a lot easier knowing that there is training and awareness.”

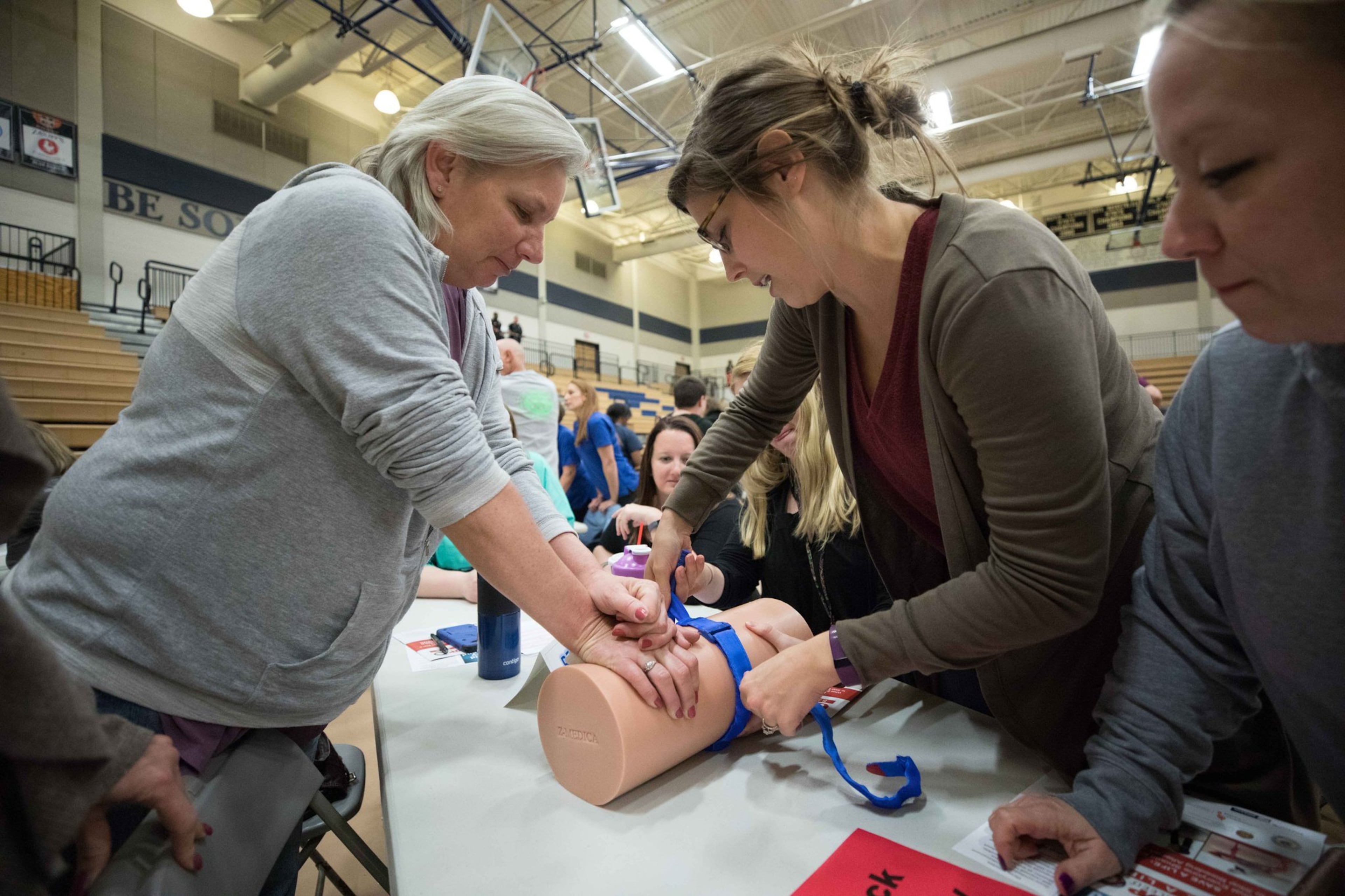

Besides training school staff about what to do during a mass shooting incident, the Monday training showed teachers what to do if someone is hurt.

“A wound doesn’t have to escalate to a fatality,” said Everett Moss, a hospital burn unit manager at WellStar, as he showed attendees how to stauch bleeding and apply a tourniquet.

Amy McGehee, a first-grade special education teacher at Nickajack Elementary in Cobb County, said she was grateful for the training.

“This isn’t just something I can use in the event of a tragedy at school. This will help in every day life with something like a car wreck,” she said. “My dad is an ER doctor and I understand the value of this. Providing aid before medical staff arrives can definitely save a life.”

Active shooter training

CRASE

Civilian Response to Active Shooter Events

Law enforcement officers and agencies are frequently requested by schools, businesses, and community members for direction and presentations on what they should do if confronted with an active shooter event. The Civilian Response to Active Shooter Events course, designed and built on the Avoid, Deny, Defend strategy, was developed by the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training program at Texas State University in 2004. It provides strategies, guidance and a proven plan for surviving an active shooter event. Topics include the history and prevalence of active shooter events, civilian response options, medical issues and considerations for conducting drills.

ALICE

Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, Evacuate training provides preparation and a plan for individuals and organizations on how to more proactively handle the threat of an aggressive intruder or active shooter event. Whether it is an attack by an individual person or by an international group of professionals intent on conveying a political message through violence, ALICE training is a more aggressive approach versus “lockdown only.” approach. ALICE proponents say it offers specifics for law enforcement, K-12 schools, higher education, health care facilities, businesses, government and houses of worship.

Run, Hide, Fight

Endorsed by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the FBI, this course of action encourages engaging the shooter as a last result. It is similar to CRASE.