Atlanta arms teachers with more detailed data to personalize lessons

School had already let out for the day, but the teachers at Hollis Innovation Academy in northwest Atlanta were gathered around tables in the library, laptops open, strategizing. Their screens showed how their students had performed on last year's state tests by subject, such as English or math, and specific domain, such as vocabulary or measurement.

Students were sorted into three categories coded by color: red for “remediate,” yellow for “monitor” and green for “accelerate” — and teachers could quickly see where they clustered.

The Atlanta Public School district is on the leading edge of the push to get helpful data to teachers in formats they can use to recognize student strengths and weaknesses and take quick action.

For years, districts nationwide have monitored standardized test data and other measures, reporting them to the state and watching trends across schools. Some districts have passed along that data to principals and instructional leaders to guide school improvement, but few have sent it to teachers, who make the day-to-day classroom decisions.

Atlanta school leaders hope that giving teachers useful, timely information about their students will lead to more effective teaching and better student outcomes.

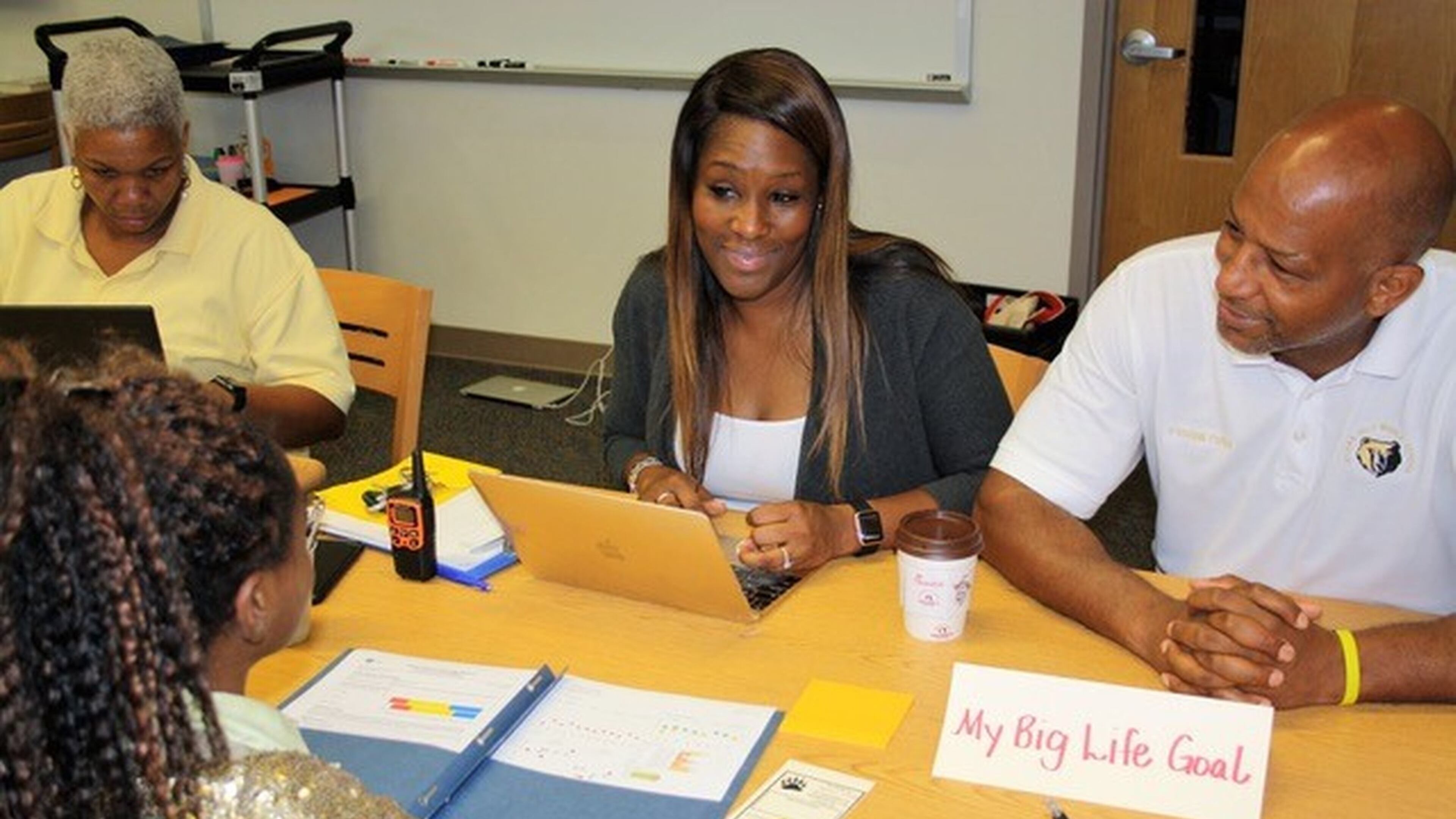

Ron Blaché and Marie Hall were comparing notes. Hall’s fifth-grade students had struggled in math and she had asked Blaché, an art teacher, if he could incorporate art projects that might help them. He knew he could get students measuring with rulers more frequently, for one.

“I just have to be more creative,” Blaché said.

They used the district’s new teacher dashboards, collections of data on each student, to sort out their ideas.

Individualized data has not often been shared with teachers because, for one, it’s complicated. Making sense of reams of data can take time teachers don’t have, and useful insights often come only after laboriously cross-referencing data stored in multiple systems.

There's also a psychological factor. At least since 2001, when No Child Left Behind set strict benchmarks based on standardized tests, teachers have had reason to fear data. It has been used punitively, to point out their shortcomings, threaten their jobs and take away their classroom autonomy. In Atlanta, an emphasis on test-based accountability once put so much pressure on teachers and administrators that it helped push some to cheat by changing student test results.

But Atlanta Public Schools and a sprinkling of districts around the country are trying to give data a new reputation. And not by turning teachers into statisticians.

Michael LaMont, executive director of Atlanta Public Schools’ Data and Information Group, is in charge of collecting data and making it easy to understand. They accomplish that with visualizations such as color-coded charts that can reveal achievement gaps or strengths and weaknesses. The data dashboards make clear which students need extra help and which need more challenging work, helping teachers tailor lesson plans accordingly.

Atlanta is in its third year of rolling out the dashboards, having started with district leaders, then moved to principals and instructional leaders for school-level performance. This year, they are offering information for teachers at the classroom level.

In northern Atlanta last summer, Will Melton, a Grady High School math teacher, pored over his dashboard to prepare for the first day of school. By the time he met his students, he already knew how they had performed in prior years, whether there were any trends in that performance and where their behavior fit in.

“Knowing and understanding that is huge information to know,” Melton said.

Melton had early access to the dashboards because he provided feedback during their development, to ensure they would be understandable and useful. Over the next few months, all of Atlanta’s 3,000 teachers will get access.

These teachers have long had access to information about their students, but the dashboards bring it into one place. Education data is notoriously fractured. State test data lives in one system, district benchmark data in another and student information in a third. In past years, teachers could find data about one student at a time, or just one year’s worth of test data, for example. Identifying trends by using data across multiple years was extremely time-consuming, if not impossible.

The teacher dashboards offer all of this critical information via several tabs on the same system

One tab shows a comparison of schools based on Georgia state tests. This shows a color-coded view of what portion of students at each school are categorized as “beginning,” “developing,” “proficient” or “distinguished” learners, giving teachers a glimpse of how their school compares to others. Teachers can also select from drop-downs to filter the data by grade level, subject, test year or student subgroups such as ethnicity, English-language learner or disability status.

Another tab offers a comparison view within a single school, so teachers can easily see where achievement gaps are. Teachers can explore additional tabs to see overall achievement, performance in a given subject such as geometry and detailed information about students.

Hall, the fifth-grade teacher at Hollis, knew from simple classroom observation that most of her students needed remediation. But the data also showed her that one of her students should be accelerated in a math domain. Now she knows she should tailor certain lessons to challenge that student.

Hollis Innovation Academy’s principal, Diamond Jack, has high hopes for how the dashboards will influence teachers. “It’s going to be a game-changer for them,” she said.

Like other high-poverty schools in Atlanta, Hollis has more students who need remediation than acceleration. It can be discouraging for those teachers to monitor this data. But principals can play a role in setting the right tone.

At Barack and Michelle Obama Academy, an elementary school in southern Atlanta, principal Robin Christian has hired teachers who are willing to track data to better understand what works.

“It’s not a bad thing if your kids don’t do well,” Christian said. “But it’s a bad thing if you don’t do anything about it.”

That’s the kind of philosophy LaMont hopes to scale district-wide. His goal is a culture change so that teachers and other staff members don’t just tolerate data, but demand it.

LaMont said one way to do this is by using data as a flashlight, rather than a hammer. Instead of drawing attention to teachers’ failures, he said the data should be used as a resource, one that can support teachers’ daily work and doesn’t require a massive investment of time.

And while the teacher dashboards aren’t fully rolled out yet, the district is already thinking about bringing parents and students into the fold.

Sylvan Hills Middle School started student goal-setting meetings last year, asking students to think about what they want to be when they grow up, and connecting their school performance with their life goals. Meeting with 600 students and creating profiles for every child — complete with grades, test performance and attendance data — took an entire semester. Administrators opted not to repeat the exercise in the spring.

This year, they were able to do it in a couple of weeks, according to assistant principal Monica Blasingame. The student profiles section of the new dashboards brings together all the information from the disparate data. LaMont’s team also created goal-setting forms online, so that as soon as a teacher discusses goals with a student or identifies strategies to meet them, the details can be logged for other teachers to see.

Eventually the district expects to give students direct access to the forms and let parents participate as well.

“That is the arc of where we’re going,” LaMont said. “Getting more people to see the data and come together to take action with it.”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.