The Fitzgerald community had high hopes for its rural hospital, started by two physician brothers then taken over by Ben Hill County in the late 1940s. The county built a new facility and expanded it through the ’90s, helping to ensure that residents of south-central Georgia had access to quality medical care.

By the 2000s, though, population declines led to years of steep operating losses. To rescue the hospital, local leaders banded together and got nearly $10 million in taxpayer-backed bonds to modernize the building. The improvements, which included a new operating room and labor and delivery suite, would help to lure more patients, officials said.

They were wrong.

Now, Dorminy Medical Center is at risk of closure. Its patient population of elderly and poor doesn’t generate enough income to support operations, while questionable managerial decisions have sunk the hospital deeper into a hole.

Similar could be said for dozens of rural Georgia hospitals. The pandemic is pushing many over the edge, and industry leaders are predicting widespread closures that will be devastating to their communities.

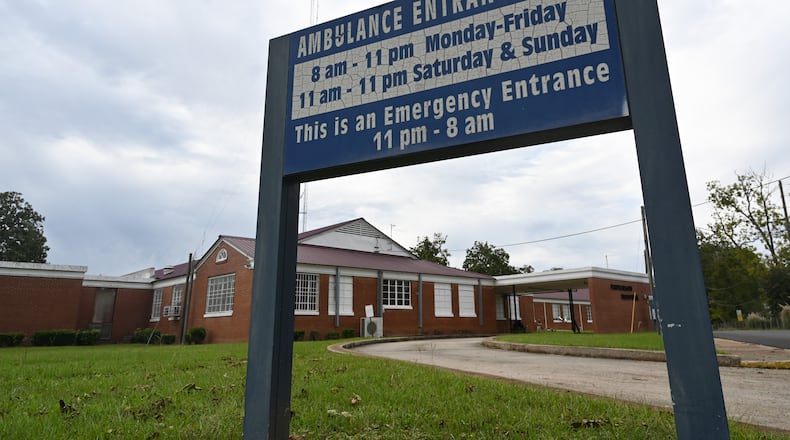

Credit: Dorminy Medical Center

Credit: Dorminy Medical Center

"We are at a push-comes-to-shove moment,'' said Michael Topchik, national leader for The Chartis Center for Rural Health, a healthcare consultant firm with offices in Atlanta. “What are we going to do as a society to basically recognize that people need healthcare where they live, and are we going to have a rural safety net or not?”

Georgia in recent years has been among states with the largest number of hospital closures, with seven shutting down from 2010 to 2019. Two more, at opposite ends of the state, have announced they will cease operations in October, with pressures from the pandemic just the last straw in their financial burdens.

While some residents in those communities will be able to drive to other hospitals, those who may be left with no healthcare alternative will be the elderly and the poor.

"People are going to die because of what’s happening to these hospitals,'' said Del Percilla, an Albany attorney with close ties to Cuthbert, home to Southwest Georgia Regional Medical Center, which said it will close in the fall.

Meanwhile, the closures likely will reverberate throughout rural counties, devastating their already distressed economies. The loss of a hospital can trigger the closures of banks, restaurants and grocery stores. Many businesses won’t consider a move into areas that lack viable healthcare.

In Ben Hill County, Dorminy provides jobs to roughly 244 employees. Total employment in the county is less than 5,000, census figures show.

Failed saves

For years, Georgia officials have struggled to address the financial plight of the state’s rural hospitals. Yet those measures have repeatedly failed.

Counties have tried to provide subsidies and issue bonds, but the economic and demographic forces weighing on rural hospitals also drain county coffers. Then as hospitals fall deeper into debt, they have to lean on taxpayers more, creating a continual crisis.

State lawmakers have tried an assortment of plans, including a state tax credit program that rewards Georgia income tax credits to individuals and corporate taxpayers who contribute to eligible rural hospitals.

In 2018, the most recent year the data is available, approximately $59 million was delivered to roughly 30 of the state’s most impoverished hospitals. The money apparently went to equipment upgrades, physician recruitment and facility renovations but hasn’t done much to improve the hospitals' overall financial health.

“It’s wonderful to provide temporary assistance,” said David Mosley, a partner at national healthcare consultant Guidehouse. "But a thoughtful, informed plan to transform these hospitals into facilities that their communities will utilize, support, and sustain is required.”

Meanwhile, the federal government over the years also has taken a stab at rescuing the hospitals. It has boosted reimbursements to those rural hospitals with no more than 25 inpatient beds and a certain distance from primary roads and major hospitals. States tried to increase the number of hospitals that fell into that category by deeming them a “necessary provider.”

“People are going to die because of what's happening to these hospitals."

Now, there’s growing consensus that federal reimbursement systems actually undermine rural hospitals’ ability to succeed. That’s because reimbursements are based on services that draw so few patients that it is virtually impossible to make ends meet.

When Southwest Georgia Regional Medical Center announced it would cease operations, it had an average daily census of no more than four inpatients yet several dozen employees — certainly the formula for failure.

"Anytime you study these, you realize pretty quickly that that’s not a business model that’s going to sustain itself going forward,'' said State Rep. Terry England, R-Auburn, a member of a statewide rural hospital stabilization committee formed seven years ago to improve the financial health of the hospitals.

Efforts to tackle the problems have stalled in Congress, as well as in the state Legislature.

And, operators also don’t have much time to troubleshoot their way out of the situation, England said. They are too busy trying to keep the lights on.

"It’s like having a building on fire and trying to put it out with buckets of water because you don’t have time to walk around and find the fire hose right around the corner,'' England said.

‘Behind the eight-ball’

Like many rural facilities, Dorminy Medical Center for years has faced low occupancy rates. With an average daily census of 11 patients, it is operating at 23 percent capacity.

Because it must spread its costs across so few patients, it spends an exorbitant amount of money on basic needs per patient, said John Minahan, an Atlanta certified public accountant who leads a healthcare company that works to revive struggling healthcare facilities.

Credit: Dorminy Medical Center

Credit: Dorminy Medical Center

Tracie Haughey, the CEO of Wills Memorial Hospital in Washington, says most rural hospitals can’t escape the adverse impact of low volumes on the bottom line. "No matter if you have one patient in the door or you have a million patients, you have to keep the lights on.

"You are behind the eight ball no matter what,'' she said.

The issue can be further exacerbated because the hospitals often draw from areas where many patients are poor. In Ben Hill County, for example, more than a quarter of the population lives below the poverty line. In Randolph County, served by Southeast Georgia Regional Medical Center, the poverty rate tops 30 percent.

That means the hospitals ante up millions of dollars in uncompensated care for those who cannot afford to pay, in stark contrast to their urban and suburban counterparts that can more comfortably support operations with higher payments from privately insured patients.

Some hospitals have also made decisions that have worsened their financial situations, said Minahan, chief executive officer of the Marietta-based RiverMend Health.

Instead of closing a few empty wings to try to reduce costs, Fitzgerald leaders over the years invested in services that see less use, such as labor, delivery and postpartum services in a community that is declining in population, he said.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

And in 2018, the hospital decided to boost salaries and wages by $2.3 million when it could instead have chipped away a $3 million deficit in operating costs, Minahan said.

“You can tell they haven’t admitted to anyone they have a problem, including themselves,” said Minahan, who reviewed the hospital’s financial records and Medicare cost reports at the request of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

"No one is making the right operational decisions to right size the company,'' he said. “You can’t fix a business until you admit you have a problem.”

But the picture is complex.

“Anytime you study these, you realize pretty quickly that that's not a business model that's going to sustain itself going forward."

Stacie Mims, chief executive officer of the hospital, told the AJC that efforts to cut unnecessary services and open new lines have been underway for months.

In March, Dorminy closed its facility for labor, delivery and postpartum services. The hospital also combined its general medical-surgical floor with its transitional care unit. Nearly three years ago, an outpatient hospice was shuttered because patient volumes could not sustain it, she said. Some departments, meanwhile, have been compressed to the point where "we don’t have a lot of wings (left) to close,'' she said.

Also, many of the nurses at Dorminy are cross trained to be able to work in more areas of the hospital. That way, the nurses are "well rounded,” she said, “and keep their skills up.”

As for the salary hikes, she said they are critical to keeping qualified staff who could go work at regional hospitals in Tifton and Valdosta.

"Anytime they have an increase in salary, that’s going to affect us,'' she said. “We try to do what we can to be as competitive as we can.”

Credit: Stephen B. Morton for The Atlanta Journal Constitution

Credit: Stephen B. Morton for The Atlanta Journal Constitution

No way to catch up

The pandemic has revealed just how much ground rural hospitals have lost.

Many struggled for years to attract and retain enough doctors and nurses. Amid the pandemic, medical staff shortages have left them unable to treat patients.

Two nurses quit in August when Emanuel County was hit with over a dozen COVID-19 patients. It struggled to handle the surge of infected patients, CEO Damien Scott said. But it couldn’t send them to larger hospitals because the facilities were full. The Georgia Emergency Management Agency sent him three nurses to help.

Many of the facilities also are decades old, often built with financial assistance from a 1940s federal program. Those hospitals lack the physical design essential to minimize the risk of transmission of any infectious disease, much less the isolation and negative pressure rooms modern hospitals have for infection control.

In Elberton, Elbert Memorial Hospital has only one entrance for patients and staff. That means COVID-19 patients cannot be isolated from others in the small lobby of the emergency room, CEO Kerry Trapnell said.

"It would be cheaper for us to build a new hospital than to redo this 50-years plus facility,'' Trapnell said.

It’s absurd how dire the situation is, said Bill Lee, CEO of Evans Memorial Hospital, 50 miles west of Savannah. Like many other rural hospitals, in the months before COVID-19 the Claxton hospital was already on the brink of closure.

The average daily census was down to three patients — not enough to trigger revenue needed to keep the facility afloat.

Then, as the pandemic hit, dozens of patients arrived, filling up every bed.

Federal pandemic relief dollars flowed in, helping prevent the hospital’s closure. But the money wasn’t enough to raise the level of critical medical services that the hospital would need in order to handle more complicated cases.

So, dozens of virus patients who needed care when the outbreak hit Evans County had to go elsewhere. They were airlifted to hospitals as far away as Florida, Kentucky and Tennessee.

"It’s a tough pill to swallow,'' Lee said. “We were able to intubate them and put them on a ventilator here, and we’ve done that frequently. But after that, where do we send them?”

AJC Investigates: The Future of Rural Hospitals

Today: Georgia rural hospitals are fighting to stay open, with the pandemic pushing more over the edge.

Thursday: Partnerships, subsidies and tax credits have failed to rescue rural hospitals.

Oct. 4: New healthcare models may replace hospitals in rural areas.

How we got the story

After two rural Georgia hospitals this summer announced that they were shutting down, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution set out to examine the complex forces that have led to closures and how a rural healthcare safety net might be preserved. For this story, the AJC compiled information from Medicare cost reports, municipal bond documents, lawsuits and other public records. The newspaper also talked with dozens of healthcare professionals, including rural hospital executives, government regulatory leaders, forensic auditors and consultants, to try to understand why so many facilities fail. To assess state government attempts to support rural hospitals, the newspaper also spoke to state lawmakers who have attempted to bring those hospitals to a solid financial footing.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured