Alana Shepherd begins her days at a round glass table in her kitchen, looking through binoculars, observing birds: bluebirds, brightly colored warblers, ruby-throated hummingbirds.

It’s a joyful ritual, a moment of stillness, before the 94-year-old goes to work.

Alana also keeps binoculars within reach inside her tiny corner office at Atlanta’s Shepherd Center overlooking the area where a stream of ambulances arrive, one after another, delivering patients with catastrophic injuries.

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

It’s bustling here: while patients enter this hospital quietly, jackhammers rumble as a major construction project is underway. Upbeat music is on blast in the therapy room.

Alana steps outside her office and gets on her red scooter she rides to buzz up and down long hallways. Even before she turns the first corner, she’s warmly greeted by staff and visitors alike. Everyone here knows the quick-witted woman with blue eyes and wavy brown hair by name — Mrs. Shepherd.

She is the Alana Shepherd — co-founder of what started back in 1975 as a six-bed unit. It’s now grown into one of the country’s leading rehabilitation hospitals, treating nearly 1,000 inpatients a year with a long waiting list.

“I do wonder sometimes, oh my gosh, how were we able to do this?” Alana said on a recent afternoon.

Shepherd Center grew out of her personal tragedy 51 years ago on an early fall morning. Alana’s son, James Harold Shepherd Jr., was bodysurfing off a beach in Rio de Janeiro when he was slammed by a wave into the ocean floor. He washed up on the beach, his body limp.

Paralyzed from the neck down by a spinal cord injury, James was unable to breathe on his own. Doctors and nurses in Brazil didn’t see much point in treating the young American.

‘Let him die’ was their advice.

Back in Atlanta, there was no medical facility equipped to care for him.

There was nothing Alana and her husband James “Harold” Shepherd Sr. could do about their son’s life-threatening accident. What they did instead was seek the best treatment and ask fundamental questions about how to care for him and others with spinal cord and brain injuries.

They poured what they learned — and a positive outlook they hold dear — into Shepherd Center.

Now, with both her husband and son gone, Alana continues the work her family began.

When she sees a patient arriving, she tells them, “It’s different here.”

Her message for new arrivals: “You are not going to be in your room. You are going to be in the gym, working hard. I know you’re ready. It’s going to get better. You are going to get better.”

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

These are patients whose lives were forever changed in an instant — a slip off a ladder, a dive into shallow water, drifting into another lane on a highway.

Alana is still on a mission to help these patients rebuild their lives and keep living — with hope.

It’s why she’s known at Shepherd as the “mama on fire.”

Caring for her son

After James’ injury, it was six weeks before his parents could finally bring him home from Brazil to an Atlanta hospital.

Doctors helped him survive cardiac arrests and overcome dangerously high fevers, but in 1973 they couldn’t offer any form of rehabilitation. By the end of his 10-week hospital stay, he had lost nearly all his muscle strength. Always a lanky man, the 22-year-old’s weight had plummeted to just 82 pounds.

James’ son, Jamie Shepherd, 44, keeps a Reader’s Digest story on his wall about his father’s injury. It’s a reminder of how the work of Shepherd Center started and the tenacity of his grandmother.

Doctors and nurses “just wanted to let him just pass away,” said Jamie. “And I always think about what a driven person she’s always been and how she made sure my father got the care he needed.”

Doctors in Atlanta strapped the injured James to a rotating bed to prevent bedsores. Sometimes he would spend hours at a time staring at the floor. Alana crawled under the bed and held magazines for him to read.

Despite the severity of James’ injuries, Alana and the family didn’t fall to pieces.

“We prayed. And we were determined we were going to do the very best we could for James — every day,” recalled Alana.

A family rule was no crying in front of him.

“She was like, ‘We are not throwing a pity party,’” said grandson Jamie. “It was always, ‘Keep it positive and uplifting.’”

But he also knows that as soon as family members left the hospital, they would pull over and “start bawling.”

Shepherd beginnings

The family knew James needed more help. They transferred him to Denver’s Craig Hospital, which specializes in spinal cord and brain injury treatment and rehabilitation.

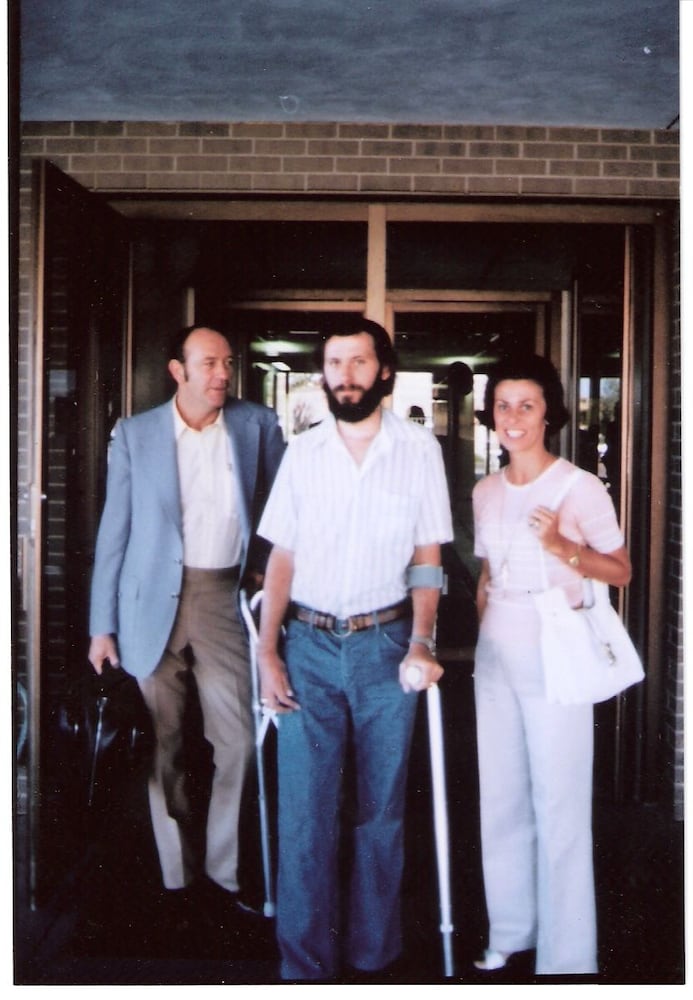

The spinal cord injury was “incomplete,” which means he had some feeling, function, and muscle control below the site of his injury. And after five months of care and intensive rehabilitation, he walked out of the Denver center with a leg brace and crutch.

Credit: custom

Credit: custom

“James and a couple other patients noticed there were a lot of people from Georgia and Florida there and they were like, ‘Somebody ought to start something like that here,’” Alana said. “And somehow that ‘somebody’ became us.”

The Shepherds had no background in health care. But they decided there was no reason a facility like Craig Hospital couldn’t exist in Atlanta — and they were in a position to possibly make it happen.

At this time, Alana was in her 40s, heavily involved in charity work and civic associations. She had become a Girl Scout leader and an elder of Trinity Presbyterian Church. Her husband Harold was the founder of Shepherd Construction Co.

Credit: custom

Credit: custom

They convinced Dr. David Apple, Jr., an orthopedic surgeon, to leave his private practice and join them as the medical director at the newly opened Shepherd Center. It was just six beds leased in an empty wing of a now-closed Buckhead hospital.

In 1975, 49 donors gave a total of $41,161 to help fund Shepherd Center. The donations inched upward little by little so that in 1980, they raised over $1 million.

By 1982, Shepherd Center was a 40-bed, free standing facility and had a waiting list.

Everyone was fair game for fundraising, especially old friends. But their biggest support would come from someone the family didn’t know: someone who first visited Shepherd begrudgingly.

Turning lives around

Hyper-focused on growing Home Depot, which had opened its first two stores a couple years earlier, Home Depot co-founder Bernie Marcus resisted pressure from a board member to visit Shepherd Center in the early 1980s.

“We were all working 60, 70 hours a week trying to get our business going, and frankly I was not interested in any charities or anything other than Home Depot,” Marcus said in a recent interview.

But one day, he recalls, that board member “wore me down.”

“I was expecting a sadness and unhappiness. All of these people who had these terrible accidents,” he said. “There were families and people who were quadriplegics — and instead everybody was upbeat. All of the patients were talking about what their life was going to be like and how they had to adapt and accept the fact they were disabled. There was this culture of ‘This happened to you. Move on. Move on with your life.’”

“I went home and told my wife, Billi, ‘I just visited the most unbelievable facility and they are turning people’s lives around,’” Marcus recalled.

Marcus joined the board, and he and his wife have been major donors to this day.

All told, Marcus and his wife and the Marcus Foundation have donated over $100 million to Shepherd. Other major donors include the Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation, James M. Cox Foundation and the O. Wayne Rollins Foundation.

The Shepherds also contributed financially, but they’ve never kept a tally of how much of their own money they donated and declined to estimate how much of their own money they’ve poured into the center.

“Alana knows every patient by name,” said Marcus, now 95, and who visited Shepherd Center in recent months. “She knows what happened to them. She knows where they are in their rehab. It’s like another world.”

“I can tell you that I am involved with many hospitals and facilities around the country and I can tell you I have never seen anything like it and I don’t ever expect to see anything like it in the future. And Alana Shepherd is the driver,” Marcus said.

In 2023, nearly 1,000 patients were treated as inpatients and more than 8,000 patients were treated in outpatient programs. Shepherd Center is a 152-bed hospital and is set to expand to 200 beds by 2030.

The center now treats a wide range of injuries including spinal cord injuries, brain injuries and other neurological conditions. They have a special program for patients in a coma or minimally conscious state after a brain injury. They can provide comprehensive care from a team of physicians, specialists, nurses and physical and occupational therapists.

Shepherd Center is also undergoing a major expansion to add about 160 housing units for patients and their loved ones, doubling the current capacity.

Alana is now the lone survivor of her nuclear family. Her husband died in 2018. Her daughter, Dana, died in 2014; James in 2018; and another son, Tommy, died in October 2023.

Two of her grandchildren, both children of James, now help run Shepherd Center: Jamie is president and chief operating officer and Julie Shepherd is director of Founding Family Relations & Canine Therapy lead.

“She’s very focused,” Julie said of her grandmother. “Now that she’s older and my dad is no longer with us and my grandfather is no longer with us, she is making sure that the hospital is going in the direction that she wants and the legacy will continue.”

“She knows what it’s like to walk in those shoes and what she would like someone to do for her.”

‘You keep fighting’

Mariellen Jacobs met Alana in early 2015, shortly after Jacobs’ critically injured son, Clark, arrived after two emergency surgeries, including brain surgery.

Clark, who was 20 at the time, had fallen 7 feet from a loft bed in his fraternity house at the Georgia Institute of Technology onto a linoleum floor and fractured his skull. He also suffered a stroke. He spent the first two and a half months at Shepherd in a near-comatose state.

“He was in pretty bad shape when arrived,” said Mariellen Jacobs. “It was dire.”

She often saw Alana in the hallways, offering a warm hello and checking in on how Jacobs’ son was progressing, and also how she was doing.

Clark underwent a second brain surgery at Shepherd to reattach his skull cap. Within hours of the surgery, Clark’s eyes were tracking around the room.

Even before Clark could actively participate in therapy, therapists would get him out bed, get him dressed and move him into a chair.

“Every day it was like, let’s see what we can do,” said Jacobs.

Once when Jacobs saw Alana in the hallway, she decided to share her idea to start a nonprofit to raise awareness for bed rails to make loft beds in dorms and fraternities safer. Jacobs asked her, “How do I go about it? What should I do?”

“Alana said, ‘You knock on every door and you don’t take no for an answer. You keep fighting. You keep fighting for what you believe in,’” recalled Jacobs, who became a volunteer at Shepherd after her son’s traumatic injury. More recently, she took a job at the center as a family support liaison.

“From the moment Alana decided this was something she was going to do, much like me with my son’s recovery, I don’t think she’s ever looked up,” said Jacobs.

Thank you

It’s well past 6 p.m., and by the time Alana takes her seat and takes small bites of barbecue pork on a recent evening at the hospital’s weekly family dinner.

Credit: Arvin Temkar/AJC

Credit: Arvin Temkar/AJC

At the dinner was Semajderia “Semmy” Graves, a young woman from Brunswick, Ga. who survived a horrific car crash but a severe spinal cord injury has left her paralyzed from the chest down. Graves, 19, said she could always count on Alana remembering her name and noticing her improvements, however small.

“She’s also always very encouraging and always looking forward to how I will continue to get better,” said Graves.

While others tend to the business of running the hospital, Alana is still so many things: a fundraiser, chairman of the board of directors, a greeter and supporter for patients and their families. She edits Shepherd Center’s quarterly magazine.

She signs thank-you letters to donors, as many as 100 a week, and adds personal messages to many of them, always using her signature pen with turquoise ink.

It’s all volunteer work because she does not take a salary. She never has.

Almost a decade ago, as Clark Jacobs recovered from his traumatic brain injury, he saw Alana at a distance in the hallway outside his room. He called out her name, and extended his hand.

He would return to Georgia Tech, graduate and get a job as a mechanical engineer.

“Thank you,” he said.

“Thank you for making this place.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured