Some stories sound more like a memory than a revelation.

That's how the news struck Israel Pattison in December when he heard two children were found buried behind their home in Effingham County. Pattison is a cousin of the kids' father, Elwyn Crocker Sr., who now faces murder charges. The dad is accused, along with four co-defendants, of starving and beating JR and Mary Crocker while keeping the young teens in a dog pen.

It isn’t that Pattison always imagined his cousin as an accused killer, but he knows Crocker and the past. Pattison said he recalls witnessing Crocker beaten terribly and demeaned for years when they were kids.

Court records obtained by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution show child welfare workers investigated the abuse of young Elwyn, just as they would with his own children decades later.

The family also lives with the shadow of Donald “Pee Wee” Gaskins, a cousin of Pattison and Crocker’s grandfather — and one of the South’s most notorious serial killers.

It all makes Pattison wonder if something in the family is broken.

“What happened in Effingham County seems like a reprise of family history,” he told the AJC.

Pattison, 45, a software engineer, sometimes talks about it as a “curse,” a strain of meanness passed through generations like an awful baton. Once it got to him, he said, he decided to drop it. He researched child abuse and intergenerational trauma, and he now believes it must’ve played a role in the deaths of the Crocker children.

MORE: DFCS vows policy changes after kids’ deaths

Several experts say he could be correct.

“Any kind of abuse in childhood lingers on, has a long tail,” said Douglas LaBier, director at the Center for Progressive Development in Washington, D.C. “I think absolutely you could say there’s a high likelihood that that stream in their evolution was a factor (in JR and Mary’s alleged abuse).”

But LaBier and others reminded: most kids who are abused don’t grow up to be abusers. They instead take it as a lesson about how not to treat a child.

Crocker was denied bond and remains jailed. At the AJC's request, Crocker's attorney, Stephen Yekel, asked his client whether he was abused as Pattison described. Crocker said Pattison is telling the truth, according to Yekel. But the attorney offered no further comment from his client, who last week pleaded not guilty.

Pattison said he doesn’t want to defend his cousin in any way. He’s appalled, disgusted and heartbroken by the allegations against Crocker. Pattison only hopes that revealing – and reckoning with – how the past might relate to the present can help those who mourn JR and Mary understand. He also hopes it can help inform those trying to prevent future tragedies.

‘A normal childhood’

Elwyn Crocker, 50, who most recently worked as an associate and seasonal Santa at a Walmart, was born of a short-lived marriage between his mother and a man from Maine. After the divorce, the mother, Mary Alice, raised Crocker and his younger brother in Columbia, S.C.

On Aug. 11, 1975, when Elwyn was seven, his mother married Larry McCoy. McCoy moved into their small house on Virginia Street and, according to court records and relatives, unleashed violence and chaos there for years. In that same year, it’s possible little Elwyn heard adults talking about another violent man: Pee Wee Gaskins. In December, workers dug up eight of his victims from shallow graves in farming country on the other side of South Carolina.

But there was horror on Virginia Street, too.

Pattison recalled McCoy, who couldn’t be located for comment, beating Crocker with a paddle. Elwyn would sob and grow quiet afterward. Another relative, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, said McCoy once hung Elwyn, clad only in underwear, upside down from a tree in the yard.

One day in 1979, McCoy allegedly blackened Elwyn’s eye and busted his nose, prompting the South Carolina social services agency to open a case, according to Mary Alice’s 1986 divorce filing. McCoy admitted in court that he’d beaten Elwyn, and he was ordered by a judge to take counseling but never did, the mother’s attorney said. McCoy’s attorney denied he abused Elwyn but said he exercised “parental control” over the child, court records show.

Reached by phone last week, Mary Alice said her son had “a normal childhood” and wasn’t abused.

The baton

When he was 8, Pattison moved to Virginia with his father. He still visited Columbia and said he watched his cousin grow into an at times cruel teenager. Pattison, who is five years younger, said his cousin’s response to being dominated by McCoy seemed to be to dominate others who were more vulnerable.

Pattison said Crocker chose him as a victim and molested him repeatedly. (Crocker’s attorney didn’t respond to that allegation.)

As Pattison grew older, he drifted farther from family in Columbia and tried to put it all behind him. He later realized he had to deal with the trauma because it contributed to toxic stress and depression. He said he was helped by therapy.

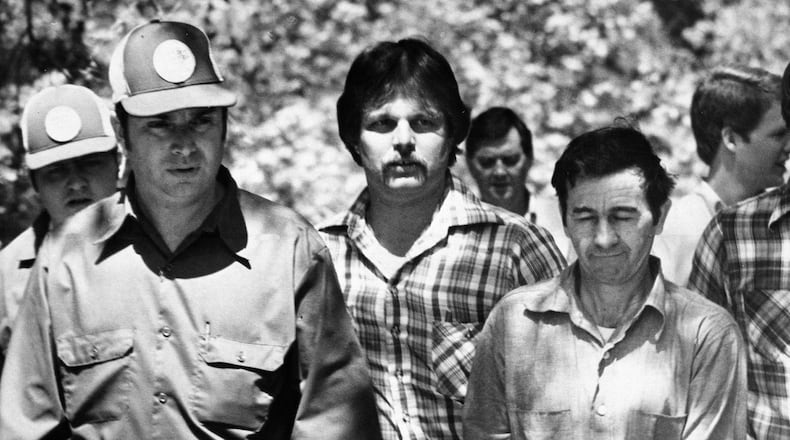

Credit: Courtesy Israel Pattison

Credit: Courtesy Israel Pattison

Pattison wishes his cousin would’ve gotten help, too.

After their grandfather’s funeral in November 2005, they didn’t see each other again. Pattison later heard Crocker had “disappeared” and might be dead.

The truth was, by 2012, Crocker had three kids by two women and had wrested custody from the mothers. He had married a different woman, Candice Crocker, and moved to Effingham County, where her mother lived.

They’d been in town only a few days when the Georgia Division of Family and Children Services was called to investigate abuse of 10-year-old JR. Candice’s brother, Tony Wright, allegedly struck him in the face after getting permission from Elwyn Crocker to discipline him, DFCS records say.

JR had a black eye, like his dad in 1979.

Elwyn Crocker complained to a DFCS worker about how badly behaved his son was. JR told the worker he deserved to be hit.

When Pattison heard JR blamed himself, he was reminded of Elwyn Crocker as a boy, a kid who thought kids were supposed to get hit, a kid being passed the family baton.

Bodies

The indictment accuses Elwyn Crocker, who investigators have said personally buried his kids, of felony murder in both deaths. It says JR died sometime around Nov. 30, 2016, Mary on Oct. 28, 2018. Both were 14 and home-schooled when they died. Also charged with their murders are Candice Crocker and her mother Kim Wright. Kim Wright's boyfriend Roy Prater and her son Tony Wright are charged with murder in Mary's death.

Because five defendants were allegedly involved, experts say there could be myriad factors at play, but the father’s childhood — and, most importantly, how he responded to it — is likely one of them. Why he responded how he did may be extraordinarily difficult to say. It’s a complex combination of personality, environment, resources and general resilience.

Pattison heard about JR and Mary on Dec. 20, the day deputies found the bodies after a 911 tip.

Pattison thought back to youth. He thought of Gaskins and police digging up bodies buried by one of his relatives.

Countless people who heard in the media about JR and Mary were trying to understand how such a thing could happen to two children.

In Pattison’s mind, pieces were just falling together.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured