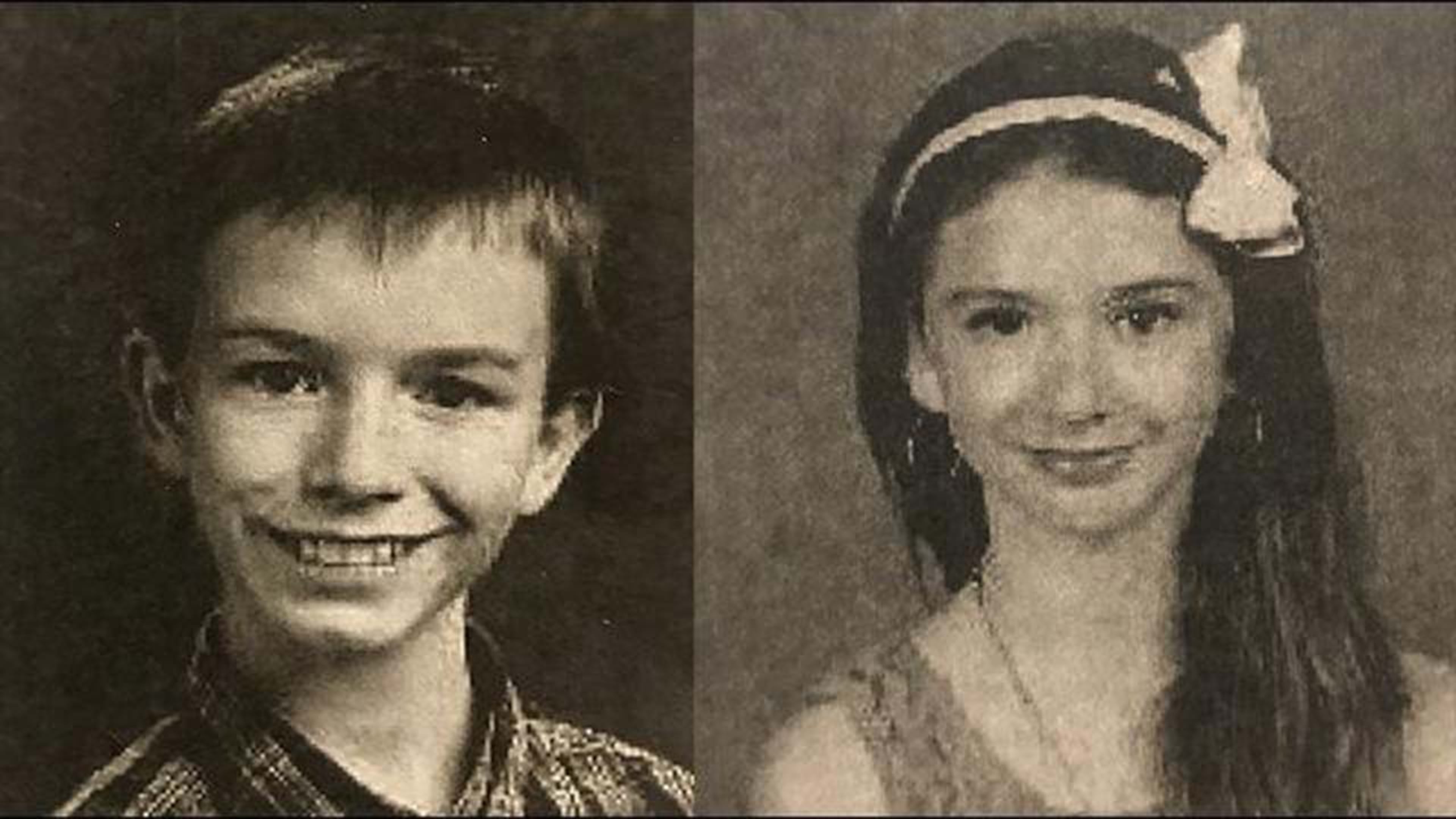

EXCLUSIVE: How systems failed to protect Effingham kids before death

SPRINGFIELD, Ga. — In court Tuesday, the attorney for Tony Wright, one of the suspects in the most shocking and sordid child abuse case in recent Georgia memory, told the judge her client should go free from jail on bond because he has no prior criminal record.

Prosecutor Brian Deal argued successfully against the bond, but he didn’t dispute the point about Wright’s lack of previous convictions. Deal knew the defense was right because he’d helped Wright avoid a criminal record back in 2013.

Long before Mary Crocker and her brother, Elwyn “JR” Crocker Jr., turned up buried behind their home here in rural Effingham County, long before anyone could’ve fathomed that Wright and four relatives would be accused of torturing Mary, Wright was indicted on a charge of cruelty to children. But the charge — alleging that Wright allegedly hit JR in the face hard enough to leave “substantial bruising” — never moved forward. Ogeechee Judicial Circuit District Attorney Richard Mallard and his assistant Deal stopped pursuing the case with just one condition: that Wright would have “no contact” with the boy.

That was just one of multiple times Georgia's law enforcement, child welfare and education systems failed to protect the children in the long path to Dec. 20, 2018, when their bodies were pulled from the ground, an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation has found. On Tuesday, authorities described the unthinkable conditions Mary endured in the months before she died; the 14-year-old was forced to live in a dog pen, starved, beaten and even Tased, a detective testified.

The defendants haven't responded to requests for comment in recent months. Like prosecutors and other authorities, the defendants are now barred from speaking publicly by a new gag order. But the case has prompted lawmakers to propose changes to a state law and the state Division of Family and Children Services to revamp a policy on reviewing abuse claims.

Through hundreds of public records and dozens of interviews, The AJC learned how loopholes and decisions by authorities helped the family dodge accountability for years. The family convinced DFCS the kids were safe in 2013. They benefited from Georgia’s homeschool laws when they pulled both kids out of public school and away from workers who could have seen signs of trouble. They caught a break when DFCS declined to investigate a brutal report of abuse of JR in 2017 — when the boy might have already been dead and Mary was still alive, crawling toward a hell barely imaginable.

DFCS believes the family

The first time JR met a DFCS caseworker, he was 11, a proper and polite student at Sandhill Elementary, where teachers found him “highly intelligent.” He wanted to be a math teacher when he grew up.

The child welfare agency had opened a case after his step-uncle Tony’s arrest for allegedly hitting him in the face in March 2012. JR defended Wright, the caseworker noted in a report, because the child felt the man, then 22, hadn’t done anything wrong. JR said he deserved to get hit because he was misbehaving. JR said the uncle had also once hit him with a strip of metal and left bruises and welts all over his behind and legs.

The other adults — who are now Wright's co-defendants in the murder case — blamed JR, too. His dad, Elwyn Crocker Sr., stepmom Candice Crocker, step-grandmother Kim Wright and Kim Wright's boyfriend all complained to DFCS about JR behaving badly. They said he played too rough and "stole" food from the kitchen.

School staff also noticed JR fixated on food, asking classmates for leftovers and eating ravenously; a counselor told DFCS people feared the boy was being starved at home. Mary, who was two years younger than JR, didn’t have that problem.

Mary, an auburn-haired girl who loved playing with dolls and riding bikes, had a brightly decorated bedroom, with cartoon characters on the bed sheets. JR’s room was “cold and dreary,” the DFCS worker observed.

The caseworker asked JR how he thought the family felt about him.

“I don’t think I’ve ever felt loved,” the boy said.

DFCS put the father and stepmother through classes and met with them numerous times. The caseworker admonished the parents and reminded them to treat the kids equally. By February 2013, the agency closed the case because workers were confident the parents would do that and protect JR from further harm, according to records.

DFCS officials have praised how workers handled the case because they’d accomplished an important goal: finding what seemed to be a safe way to keep the kids with their family and out of the state’s overstretched foster care system.

Step-uncle gets a break

It isn’t clear if DFCS and the district attorney’s office communicated, but later the same month, the prosecutor moved to stop the child cruelty case against Tony Wright. The charge wasn’t dropped; instead, the DA’s office used a process called “dead docketing,” which pauses a case indefinitely. Dead docketing leaves prosecutors the option to re-open a case at any time, but they left Tony Wright’s closed.

Generally speaking, dead docketing is something a prosecutor might do if there are some difficulties in the prosecution, such as witness cooperation or an absconded defendant. Danny Porter, the longtime Gwinnett County DA and former chairman of the Prosecuting Attorney’s Council of Georgia, said the practice is most common in smaller jurisdictions with limited resources.

Agreements like the one made with Tony Wright can be “very effective” in stopping a defendant’s criminal behavior, Porter said — if the defendant takes the situation seriously.

How seriously did Tony Wright take it?

Two former neighbors told The AJC they regularly saw him at JR’s house a few years later. Kristy Cook, who lives next door to the home where JR and Mary were found buried, said Tony Wright and JR both seemed to be living there in August 2015 when her family moved in.

Partnership Against Domestic Violence CEO Nancy Friauf said prosecutors not following through with child abuse charges is not uncommon — and not a good idea. “It can give the perpetrator of violence the message that, ‘You’re not going to be held accountable,’” Friauf told The AJC.

Kids pulled from school

In the cold search for answers after JR and Mary’s deaths, many have wondered if homeschooling enabled their plights.

JR was pulled from South Effingham Middle School halfway through 6th grade in January 2014. Mary was pulled from Effingham County Middle before she was set to start 7th grade on Aug. 2, 2018.

Experts say traditional school can help stop abuse because it gives children a safe place to disclose abuse to adults. School staff can also notice signs. There are, indeed, horror stories from all over the country where profound abuse went undetected in homeschooled kids. In Gwinnett County, the DA said 10-year-old Emani Moss’ parents allegedly removed her from public school to avoid staff’s prying eyes in the months before the girl’s emaciated, burned body was found in a trash can.

But several longtime children’s advocates said such cases are extremely rare and Georgia lawmakers should be careful not to put undue scrutiny on homeschooled families.

“Without reason for suspicion, there is no basis to inflict on children the terrifying, humiliating ordeal of being investigated and interrogated, or the scars of having their parents’ caretaking called into question,” said Matthew Fraidin, a professor at the University of the District of Columbia.

Still, some Georgia state legislators, spurred by the Crocker case, hope to find a balance between protecting families’ rights to homeschool and children’s safety. House Majority Leader Rep. Jon Burns, R-Newington, is pushing House Bill 530, which passed the House on Thursday night and now goes to the Senate for consideration. The current version would direct school workers to ask DFCS to investigate if parents fail to submit a declaration of intent to homeschool to the Georgia Department of Education within 45 days of withdrawing them. The DFCS inquiry would be “limited to determining whether such withdrawal was to avoid educating the child,” the bill says.

Randy Shearouse, Effingham County’s school superintendent, said as far as he knows, the family didn’t file notices of intent to homeschool JR and Mary. (The state education department declined to say whether Shearouse was correct because of privacy laws.)

“This was pure evil in this case, and sometimes that’s difficult to combat,” Shearouse told The AJC. But he thinks the proposed 45-day policy could have helped.

Even so, the court testimony Tuesday painted the suspects as determined to do wrong how ever they had to. Even after Mary died, her homeschool program kept getting completed assignments in her name, according to detective Abby Brown.

Brown testified the suspects were doing the work themselves to pretend Mary was still alive.

The last break

The big moment, the one where several experts believe at least Mary theoretically could've been saved, came in March 2017. A student came forward to a school counselor to tell a story about JR being beaten for more than an hour with a belt and then forced to drop his pants to show off the red marks. The girl said she'd witnessed it about a year earlier. The counselor referred it to DFCS.

At the time, authorities didn’t know JR hadn’t been seen alive since November 2016, when he was 14.

Had DFCS workers gone to check on him, they might've discovered he was gone. They might've seen Mary outside, doing yard work constantly, as JR had done before he disappeared. They might've noticed, as neighbors say they did, that the girl looked perpetually terrified.

But DFCS didn’t go to the house. Workers declined to investigate the student’s report because it was deemed “historical.” The agency has since vowed a policy change to better respond to such reports because of what happened to the Crocker children.

Detectives haven’t yet detailed exactly what they believe happened to JR, but Tuesday’s testimony revealed the evidence about Mary.

Sometime after the beginning of 2018, detectives believe the family started keeping Mary in the dog pen in the kitchen, nude. It was allegedly punishment for familiar transgressions accused in the household: not doing chores and “stealing” food. So, the investigator said, the family gave Mary less food and beat her.

She lost weight until she was gaunt and looked near death.

On Oct. 28, she died and her father allegedly went out to the backyard and began to dig a new hole for another body.

READ: ‘God bless y’all’: DeKalb man’s life sentence overturned after 19 years

READ: Cotton candy or meth? ‘Failure of the system’ leaves Ga. woman jailed

READ: How a mysterious disappearance nearly destroyed a woman's life