Donnie Lance’s last breaths and what his death means

The end had arrived Wednesday night for Donnie Lance and everyone who’d spent decades arguing over what kind of man he was and if he needed to die.

The clock in the execution chamber read 8:51 p.m. Lance, 66, lay with every limb strapped to a gurney, a white sheet draped over his body. He declined to make a final statement, or hear a final prayer. He closed his eyes and didn’t survey the several dozen people who filled three wooden pews to watch him take his punishment for the 1997 murders of his ex-wife and her boyfriend in Jackson County.

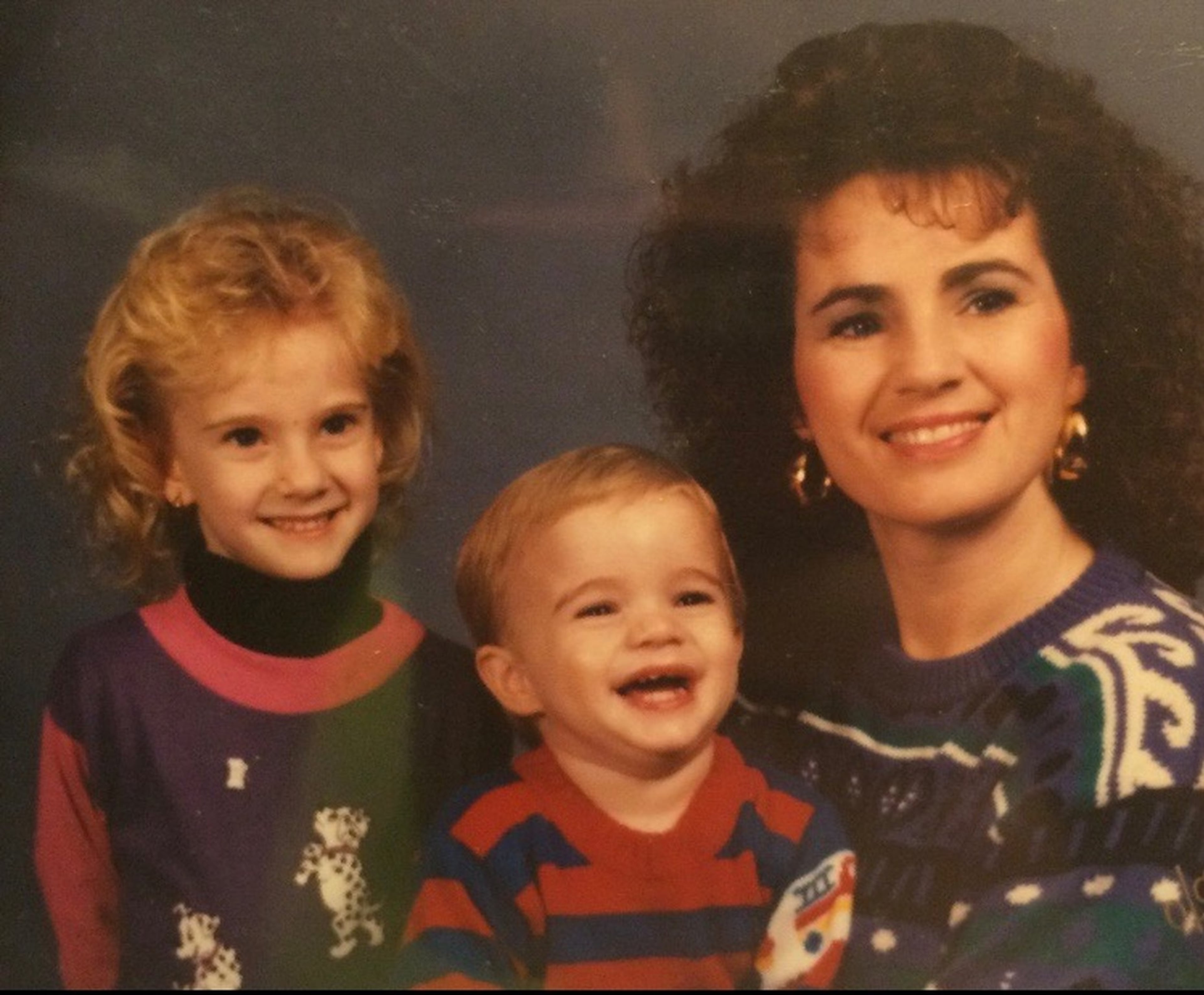

Lance had always said he was innocent, and his kids were inclined to believe he didn’t kill their mother. They couldn’t reconcile the man portrayed in the court documents, who brutally stole two lives in a fit of gunfire and beating, with the man who loved them deeply and told them over and over: “Treat others the way you want to be treated.” The kids had fought for DNA testing on evidence to confirm whether their dad was guilty, and every court told them no.

In the front row, on the other side of a large glass window from Lance, 83-year-old Dwight Wood Sr. sat in a wheelchair, with oxygen tubes plugged in his nose. He stared at the man convicted of shooting his son, Dwight “Butch” Wood Jr., 33, amid fights over Lance’s ex-wife Joy Lance, 39. Since the killings, Wood had missed his son, the one he knew as a good man who wanted no trouble, who worked as a truck driver and worked hard.

Now the elder Wood heard the warden finish reading the death warrant, and Wood kept his eyes on Lance as the pentobarbital started to flow through the IV lines at 8:54 p.m. The room was quiet but for people clearing their throats, recovering from winter coughs.

In the second pew, several seats were empty. Jessie Lance, 30, had told his dad he’d be there because he didn’t want the last thing his father saw in life to be hatred in the eyes of the witnesses. But the father told the son not to come, so he wouldn’t have to see him killed. Jessie Lance and his sister Stephanie Cape, 34, had spent time with their dad hours before his execution, telling old stories, praying, trying to take comfort in the fact that their father had been saved spiritually and intended to go to heaven.

After leaving the prison, they gathered with other relatives up in Jackson County. Cape’s mother-in-law made a huge feast, hoping they could eat while waiting for news of what happened in the death chamber 80 miles south at the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison.

» MORE: Condemned man's children call for DNA tests

» MORE: Georgia parole board grants clemency for only the 12th time since 1976

» READ: DNA analysis frees Ga. man wrongfully convicted of rape after 18 years

Donnie Lance’s kids tried to think of better things, like that Christmas — their parents always made Christmas seem magical — when Santa brought little Jessie a cowboy hat, and his dad told the kids to look out the window. In the yard, they saw their new pony. They never saw their parents fight. They remember a good life with their dad and mom, a dark-haired secretary who had a buoyant presence and a kind heart. Joy Lance’s kids couldn’t believe — couldn’t be convinced — that she would want this execution, for them to hurt from losing their last parent.

At 8:56 p.m. Lance let out a large puff of air. His mouth fell open.

Those gathered in the room, who were mostly officials and Georgia Department of Corrections employees, looked straight at Lance, trying to see if he would move. Others looked at the floor. A sour expression formed on the face of a prison system employee in a black suit. He looked at the inmate, then at the floor, back and forth.

Tammy Dearing, Butch Wood’s sister, sat next to her dad’s wheelchair and kept thinking how peaceful Donnie Lance’s death looked. So much more humane than the pictures she’d seen of her brother’s body in court. Those images still torment her. Her brother, ravaged by buckshot. Her brother, who she could still see sleeping in a tent with her young kids one night. Butch Wood had sneaked up on them to jokingly scare them while they camped in the yard, but they were so frightened he felt bad and promised to stay with them. Dearing remembered her brother’s feet jutting out of the too-small tent. She thought Donnie Lance should’ve been killed a long time ago.

Donnie Lance’s lawyers also weren’t in the death house, because they’d spent all day and night filing court motions trying to save him. They argued the death sentence should’ve been thrown out because the jury knew nothing about the repeated head traumas Lance had suffered in accidents during his career as a race car driver, and the time the lawyers said he was shot in the head during a fight with Joy Lance and Butch Wood. Experts had testified in later court hearings that his IQ was borderline for intellectual disability and that he had brain damage.

» INTERACTIVE: The faces of Georgia's Death Row

» PHOTOS | Georgia's Death Row: Those executed and their victims

» SPECIAL REPORT: How lethal injection works

Donnie Lance’s kids had always thought he seemed normal enough, even after they’d heard doctors say he had a form of dementia. Until one day, his daughter realized he always had a notebook with him. As long as she could remember, he’d been writing things down: dates, times, names, everything. When asked about a detail, his response often began with, “I’ve got it written down …”

By 9 p.m., the color had left Donnie Lance’s face. His arms went pale, then his hands. But it wasn’t over. The doctor standing next to Lance kept standing, watching the inmate’s chest until 9:04 p.m., when two more doctors walked up to Lance to check if he was still alive.

Up in Jackson County, there was a 2-year-old girl who loved her “Papa Don.” He was her grandpa who lived in prison. She didn’t know why he lived in prison and other people didn’t. And she didn’t know his fate. Two weeks earlier, the little girl had seen Papa Don for the last time, when he took her in his arms, squeezed her and closed his eyes.

» READ: A Georgia inmate's final moments and his stepbrother's loss

» READ: A daughter's last words to her father before his execution in Georgia

At 9:05 p.m., the doctors put stethoscopes to Donnie Lance’s chest. They heard silence.

Two hours later, after Jessie Lance had sat with the news that his dad was dead, the son wanted to know what his father said right before death. The last word Donnie Lance said was “no,” when asked if he wanted a final prayer.

Jessie Lance hoped he already knew the last thought his dad had. Earlier in the day, while the kids were visiting, the son — fearing that his father might be afraid or anguished when the execution started — offered a piece of advice, a final gift.

If you have bad thoughts, the son told the father, think of us.

HOW WE GOT THE STORY

This article is an eyewitness account of the death of Donnie Lance on Jan. 29, and is informed by interviews with Lance’s children, relatives of victim Dwight “Butch” Wood Jr., and others.

GEORGIA EXECUTIONS

• Donnie Lance’s execution Wednesday night was the first in Georgia in 2020.

• Jimmy Meders was scheduled to be executed on Jan. 16, but in a rare move, the State Board of Pardons and Paroles commuted his sentence to life without parole.

• Keith “Bo” Tharpe’s execution could have been rescheduled at any time, but he died this year, likely of complications from cancer, on Jan. 24, according to his attorneys.

(Tharpe originally was to receive a lethal injection on Sept. 26, 2017. But the U.S. Supreme Court issued a stay of execution amid concerns that a juror’s racist views led to Tharpe’s death sentence. The case was sent back to a lower court for review, and that court rejected the appeal.)

• Three inmates (Scott Morrow, Marion Wilson and Ray Cromartie) were executed in 2019.

• Georgia’s death row now has 41 inmates (40 men and one woman).

SOURCE: Georgia Department of Corrections