It’s likely that only some of the roughly 300,000 people a day who pass through Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport and the Maynard H. Jackson Jr. International Terminal are familiar with Jackson’s story.

But the former Atlanta mayor’s persistence and political savvy combined into a legacy that is literally built into the airport itself.

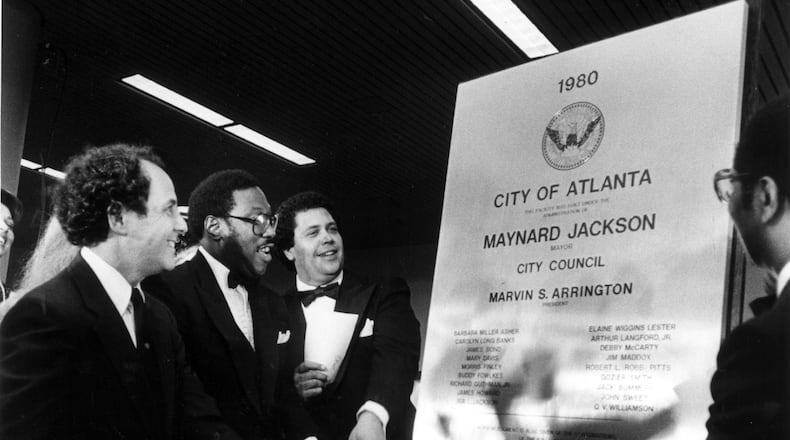

That’s because the construction of the domestic terminal — completed in 1980, along with scores of airport projects in the decades since — have involved Black-owned, female-owned and other minority-owned companies that previously never had such a chance. White contractors historically received 99% of the work before, Jackson created a plan for woman and minority-owned firms to get 25% of the work.

Jackson encouraged collaboration between white and Black-owned companies, through joint ventures and partnerships for airport contracts with minority participation. Among the Black-owned businesses in Atlanta that played key roles in the new airport terminal were H.J. Russell, a construction firm, and Paschal’s, a food service firm that was a joint venture partner for concessions in the terminal. Both businesses have grown significantly in the decades since.

And the hard-won compromise on naming of the airport itself — for former Atlanta Mayor William Hartsfield and Jackson — is symbolic of The Atlanta Way, with the white and Black business class coming together on racial issues.

Jackson established the roots of minority contracting that is used around the country today when he demanded that minorities be allowed to take part in the design, planning and construction of the airport’s terminal and concourses.

“How business is done at the airport — that’s changed forever,” said Vincent Fort, a former state senator.

That was in the 1970s. Now, minority contracting extends well beyond Atlanta and the airport. In 1983, Congress enacted the first Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) requirement. The provision required the U.S. Department of Transportation to ensure that at least 10% of the funds authorized for highway and transit federal financial assistance programs be spent with DBEs.

“It was moral conviction,” former mayor Shirley Franklin said.

Franklin added that Jackson believed: “I have an opportunity to change the trajectory and to change the way government views its business activities. And I’m going to take a little risk, whatever it takes, to accomplish that.”

“Are there people like that today?” Franklin asked. “If you look at what California has done on environmental legislation, you would say yes, there are people like that.”

To be sure, there have for decades been criticism and challenges to minority contracting programs. The Atlanta airport has faced legal challenges in recent years related to minority contracting requirements in an airport spa contract and an airport baggage system contract. Some airport concessionaires in 2012 faced challenges to their qualifications as disadvantaged businesses. For years, the city and airport were embroiled in a lawsuit against an airport advertising contractor and its minority partner.

In 2020, the city’s former director of its Office of Contract Compliance managing minority contracting programs, Larry Scott, was sentenced to two years in prison after admitting that he failed to disclose work for a company that helped other firms win contracts with the city and other local governments.

There have also been businesses that have struggled to advance beyond the role of minority subcontractor to a prime contractor competing with large multinational firms.

“It is a work in progress, no matter if you’re doing it right,” said Leona Barr-Davenport, who has since 1998 been president of the Atlanta Business League, a minority business development association. “It is an evolution.”

Jackson also executed a long-envisioned plan to construct the terminal, which required moving a section of I-85 to the curve it currently makes around the west side of the airport.

“He understood at an early age, he understood that developing the infrastructure — the infrastructure known now as Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport — was the linchpin,” said Franklin, who got a call from Jackson requesting a meeting not long after she was elected mayor with a term starting in 2002.

She recalls that he told her: “I just want you to know that the Atlanta airport is the goose that lays the golden egg. Don’t ever get confused. ... The amount of investment is the difference between Atlanta and many other cities.”

Jackson’s advice became particularly relevant when Atlanta-based Delta filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2005. Franklin said she and Andrew Young, the former mayor and ambassador, called then-Delta CEO Gerald Grinstein to say: “We are here.”

After Jackson died in 2003, Franklin brokered a deal between a contingent that wanted to rename the airport for Jackson and others who opposed the change.

The debate raged for weeks, and Franklin appointed a 17-member committee to release a report and recommendations. The ultimate decision was to compromise with the double-barreled name of the airport, and to name the future international terminal for Jackson. The Maynard H. Jackson Jr. International Terminal eventually opened nine years later, in 2012.

Credit: Hyosub Shin, hshin@ajc.com

Credit: Hyosub Shin, hshin@ajc.com

Some people are still accustomed to calling the airport Hartsfield. In 2015, his widow Valerie Jackson pushed for the airport to encourage the use of the full name of the airport, and the city council passed a resolution tasking the airport with addressing the matter.

Then-airport manager Miguel Southwell developed a plan for a branding campaign with the tagline “Two Men. One Vision” that included advertising and posters to educate travelers and others on the airport’s namesakes. The airport also sent messages to companies and government officials asking them to be sure to use the proper name in training materials, websites and documents.

Credit: BRANT SANDERLIN / BSANDERLIN@AJC

Credit: BRANT SANDERLIN / BSANDERLIN@AJC

Today, the national and international connectivity enabled by Hartsfield-Jackson and Delta’s Atlanta hub making it the world’s busiest airport has prompted Fortune 500 companies to relocate to Atlanta and countless other businesses to establish offices in the metro area.

That, in turn, makes it a draw for young people looking to start their careers and others seeking to start businesses or advance professionally, providing the foundation for upward mobility. Delta’s hub also boosts Atlanta’s role as an international city, allowing it to overtake other cities like Birmingham as the unofficial capital of the South.

“Mr. Jackson was a visionary,” said Hartsfield-Jackson General Manager Balram Bheodari. “He had a vision to take this airport globally.”

For Atlanta, the airport is ”our Mississippi River. It’s our New York harbor. ... It’s our Nile,’ Franklin said. “Every community has a portal of commerce,” and for Atlanta historically it was the railroads, and then it became the airport.

Maynard Jackson’s mark on the Atlanta airport

At Hartsfield-Jackson, there are several places to learn about Maynard Jackson.

- Displays on Maynard Jackson and others in A Walk Through Atlanta History, a permanent installation in the underground walkway of the Plane Train tunnel between Concourses B and C.

- Bronze relief plaques of mayors William Hartsfield and Maynard Jackson at the back of the main security checkpoint in the domestic terminal, on the right side of the top of the escalators after you pass through security screening.

- A portrait of Maynard Jackson in the international terminal lobby, in a public area on the upper level of the international terminal in front of the security checkpoint.

- The airport also plans an exhibit on the history of Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, to be installed in the underground walkway between Concourses D and E. It will also include displays on Maynard Jackson, according to Hartsfield-Jackson General Manager Balram Bheodari.

Credit: Melissa Bugg

Credit: Melissa Bugg

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured