Renowned scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. has carved out an impressive niche with PBS over the past 15 years with his explorations of famous people’s genealogical roots via “African American Lives” in 2006, “Faces of America” in 2010 and “Finding Your Roots” since 2012. He also did a six-episode deep dive into African-American history for PBS in 2013.

His latest effort again explores four centuries of the African-American past but through a very specific lens: “The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song.” It’s a four-hour documentary airing Tuesday and Wednesday on PBS stations nationwide. Gates also wrote a companion book with the same title that comes out Tuesday.

The series was largely finished by the time the pandemic began and before the George Floyd protests.

But Gates, in an interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution last week, said the timing worked out just fine.

“I wanted to make a series about the sheer transcendent power of belief and never has that been more important than today,” Gates said. “These stories of grace and resilience and redemption and hope and healing are so desperately needed.”

The importance of the Black church is hard to understate in developing many key Black social, cultural, educational and political institutions that endure to this day.

“It’s where our ancestors learned to read and write, to transact business from their own social institutions,” he said. “Nobody was giving money to Blacks-owned businesses. Churches were built on the nickels and dimes of normal working Black people. It’s where they learned to worship a liberating God.”

During the early years, he noted, “It wasn’t only about eternal life and doing good and getting to heaven. It was about creating a heaven on earth. And by that, I mean by fighting for the rights of Black people politically.”

The church helped provide many Blacks a sense of control even under slavery. They continued to fall in love and have children. They still found joy and laughter and music. “It was through the church they learned to defer gratification,” Gates said. “That is the most important miracle to me of the Black church: a belief in a future where their children or grandchildren would one day be free.”

Covering four centuries of history in four hours was challenging, but ultimately, it’s what Gates said he could afford.

Each hour unfolds chronologically, and he wanted to weave in interlocking themes including the origins of denominations such as the Baptist, Pentecostal and Methodist churches and how the church built self-respect. “You could be denigrated six days a week by white racism, but once inside the church building, you were king and queen. You were men and women with dignity,” said Gates, 70, who went to church regularly growing up in small town in West Virginia.

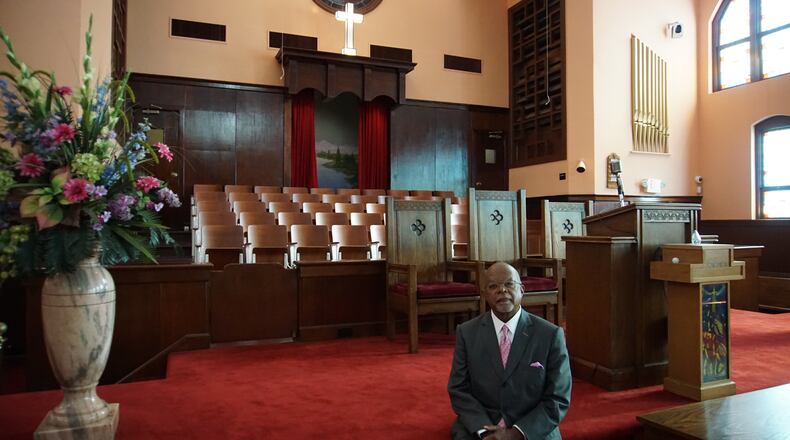

The series ends with Gates visiting his childhood church for the first time in decades. It was executive producer Stacy Holman’s idea to film him there.

Gates resisted at first, not wanting the series to focus on him. “She begged me and implored me to come back,” he said. “In the end, it was moving just to walk into that church I hadn’t been in for 50 years.”

There, Gates told a powerful story about being 12 years old and praying to God after his mom fell ill. She recovered, and he was saved.

“A colleague of mine said it was like the prodigal son coming home,” said Holman, who worked on the project with Gates for 14 months.

Given Gates’ deep Rolodex, they had no shortage of options in terms of academics, pastors and celebrities who would talk about the Black church. He crisscrossed the country, spending time with Oprah Winfrey, Al Sharpton, Jennifer Hudson, Kirk Franklin and Cornel West, to name just a few. John Legend ended up becoming an executive producer. And more than two dozen women ended up on camera, Gates noted.

Credit: PBS

Credit: PBS

The series spends plenty of time in Georgia. Gates visits Sapelo Island, where there were practicing Black Muslims in the 1600s. He goes to Savannah, where one of the oldest Black Baptist churches exists. Atlanta, of course, is the cradle of civil rights. He interviewed musician the Rev. Dwight Andrews of First Congregational United Church of Christ in Atlanta, Patrice Turner, a musician at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta and Andrew Young, former Atlanta mayor and civil rights legend.

And before the Rev. Raphael Warnock ran for Senate, Gates sat down with him as head pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church. Warnock provided an anecdote used in the series about Prathia Hall, a woman who offered her own “I have a dream” vision after the Ku Klux Klan burned Mount Olive Baptist Church in Terrell County to the ground in 1962. Martin Luther King Jr. was there and used that thematic in his own speech during the March on Washington.

The documentary has no shortage of music in it as the church is where many key musical styles evolved, from spirituals to blues to jazz to R&B.

And the church’s impact on politics is undeniable. “Black people were never allowed to be apolitical with the specter of white supremacy and anti-Black racism,” Gates said. “It haunted them every minute of every day of their lives.”

The idea of “40 acres and a mule” stemmed from a meeting Union Army general William Tecumseh Sherman had with a group of powerful Black ministers in Savannah in 1865. Gates covers the early days of Reconstruction when 16 Black men were voted into Congress, to the powerful pragmatism of pastor Adam Clayton Powell Jr.’s 26 years in the House after World War II to Rev. Jesse Jackson’s run for president in 1984.

Then there’s the 2008 election of President Barack Obama, whose pastor the Rev. Jeremiah Wright was vilified by Republican critics for condemning statements he made about America that were used in many political ads. Gates talks to Wright and provides a nuanced exploration behind Wright’s seemingly incendiary words in clearer context.

The series does not ignore the blind spots of the Black church: the sexism and discrimination against the gay community.

“We’re doing a historical film,” Holman said. “It’s important to show all facets, even pulling up the rug to show the mess. There was righteous discontent. It’s a conversation we want to encourage people to have. The church is evolving and changing just as we are.”

For Gates, the entire series is “a tribute to the Black church, warts and all. It’s a celebration every Sunday on Martha’s Vineyard in July and August when I go to the Union Chapel. It’s the feeling I get, the feeling of being comforted by a warm blanket.. That’s the feeling I wanted to create in this film.”

Credit: Credit: Courtesy of McGee Media

Credit: Credit: Courtesy of McGee Media

ON TELEVISION

“The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song”

9 p.m. today and Wednesday. GPB8 and PBA30 in Atlanta and PBS stations nationwide

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured