Lt. William Hoyle Nesbit, 21, was languishing in a Virginia hospital after having his arm shot off in the Battle of Gettysburg.

A caregiver, trying to help, sent a dictated telegram to Nesbit’s father on July 14, 1863. Knowing only that the father lived in Atlanta, he sent the telegram in care of the Atlanta Daily Intelligencer, the city’s dominant newspaper during the Civil War.

“Dear Father — I am at Jordan Springs Hospital, near Winchester. I lost my left arm at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Come to me. Answer by telegraph.”

The paper printed the desperate message, and odds are it reached its target. The Intelligencer had a circulation of 3,000 in 1860, when Atlanta only had 10,000 residents. The pass-along rate certainly doubled that number of readers.

Flourishing from its founding in 1849 until it was crushed by The Atlanta Constitution in 1871, the Intelligencer was the city’s best source of information on the war that was devastating the country.

In between accounts of the bloodshed in Shiloh and Chickamauga, the Intelligencer also offered news on local crime, gossip on drunken citizens fined for obscene language, and adverts for patent medicines guaranteed to prop up the “manhood” of its customers.

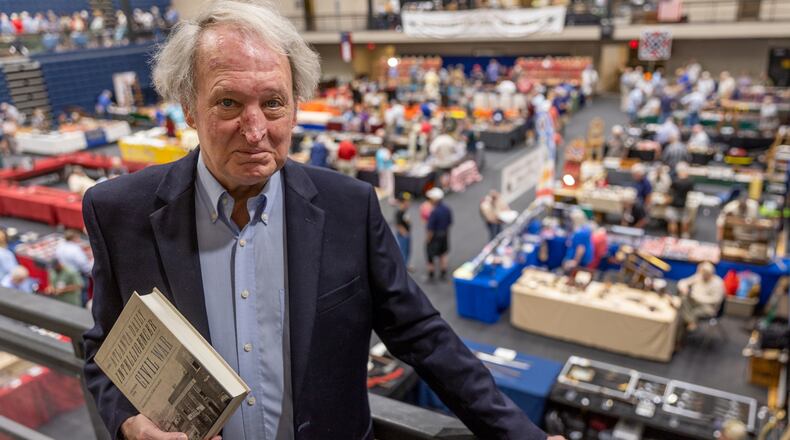

Historian Stephen Davis and longtime journalist Bill Hendrick (an alumnus of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution) spent six months reading every wartime edition of the six-day-a-week newspaper, from the shelling of Fort Sumter until the surrender at Appomattox.

Credit: Stuart Thurston Hendrick

Credit: Stuart Thurston Hendrick

The periodical’s wildly subjective view of the war provides the grist for Davis’ and Hendrick’s new history, “The Atlanta Daily Intelligencer Covers the Civil War” (University of Tennessee Press, $40), a unique vantage point into the psychology of the times.

Contemporary readers familiar with today’s hyperpartisan political coverage might yet be shocked at the extremes of language in the Intelligencer, not to mention its creative flair. The despicable Union soldiers, wrote the Intelligencer, were “Dutch immigrants, cheated Irishmen, bamboozled mongrels, miserable contrabands, miscegenating adults and brigades of silly youths with cerulean abdomens, and a sufficiency of yankees to leaven the whole mass with their accursed principles of injustice and wrong.”

“The Intelligencer is revealed to be, like most newspapers of the Confederacy, a propaganda organ,” said Hendrick.

The newspaper’s owner Jared Whitaker, grandson of a Georgia governor, was a lawyer and a city councilman and respected member of the community.

His editor was former state legislator John H. Steele. The newspaper was, from the start, an anti-Lincoln, pro-slavery political organ.

After Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, the Intelligencer came out vigorously in favor of secession, promising “the yoke of Black Republican rule, unless we rise up to our defense.”

Credit: University of Tennessee Press

Credit: University of Tennessee Press

In 1860 there were 844 newspapers in what would become the Confederacy. By 1865 that number was down to 253, only 20 of them dailies. One of the survivors was the Intelligencer, though it had to raise its rates eight times during the war, from $6 a year to $10 a month.

It was a shoestring operation. The four-page publication didn’t have a full-time reporter until 1862. It was plagued by increasing paper costs, rudimentary communications and the fact that so many potential pressmen had gone off to war. When Sherman began shelling Atlanta the paper pulled up stakes, ran south, and became the Macon Daily Intelligencer.

In its favor was a policy that gave reporters, editors, compositors and printers an exemption from the draft, which indicated the crucial role that such media served in the Confederacy.

Gordon Jones, senior military historian at the Atlanta History Center, said the new book by Davis and Hendrick is “an immersive voyage into a wartime South you’ve never seen before.”

Not many historians have conducted such a “microstudy” of one newspaper he said. “When we read the history of the Civil War, we think just in terms of battles and campaigns,” said Jones, “but on the home front life goes on. There’s still businesses, they are still selling people, there’s murders, there’s sensational stories.”

The authors point out the “factual distance” between reality and what the paper told its readers, said Jones.

On July 8, 1863, five days after the defeat at Gettysburg, the Atlanta paper was still reporting optimistic news from Pennsylvania, and ran a headline that said “The Yankee Army Routed and 10,000 Prisoners Taken.” The truth wouldn’t be revealed for many weeks.

The inaccuracy of the Civil War papers were partly due to the insistence of outlets such as the Intelligencer to report defeats as victories and maintain an insane optimism. But there were also barriers to newsgathering. Telegrams were expensive. Few reporters were in the field. Accounts, often referred to as “letters,” were sent in by mail, or wagon, or train.

To supplement their news, most newspapers shared their pages with each other, printing what they called “exchanges” and providing a kind of cut-and-paste journalism.

An example of one of these “exchanges” appeared in The New York Times, an account of the bombardment of Atlanta, written by a reporter from the Intelligencer and full of sarcasm. The writer mentions the shelling of a funeral party in which no one was killed but many monuments were battered and broken.

“This must have been exceedingly delightful amusement for the people who are trying to teach us Christianity and recover us from barbarism by effective force measures,” wrote the droll correspondent.

It was clear that the paper was read by the powerful and well-connected. The evidence of this is the official reaction to an unsigned editorial in which the Intelligencer criticized Jefferson Davis for neglecting Atlanta before and after the arrival of Gen. William T. Sherman.

After that editorial ran, Davis gave a speech in Macon where he thundered that the man who wrote that editorial was a “scoundrel.” Editor Steele was chagrined — he had been out of town while his associate editor Dr. I.E. Nagle penned the controversial opinion, but he backed up Nagle anyway.

“When the president of the Confederate States singles out your newspaper, it’s a big deal,” Davis said.

The end of the war brought misfortune to the Intelligencer. Changing political winds put the paper out of synch with the power brokers. Steele died in January 1871, and a few months later Whitaker “sold all of his printing equipment for $4,000 in a public auction (the Constitution bought it).”

By the time of his death in 1884, the formerly influential Whitaker was a broken man. He had lost three of his five brothers in the war (as well as an infant son) and most of his fortune.

The book quotes Isaac Avery, who published a history of Georgia in 1881, writing that Whitaker had taken to drink, “drifting down socially,” becoming, “a sad spectacle, seedy, impecunious and pitiful.”

Harsh.

But despite its manipulative, sometimes mendacious reporting, the Intelligencer served a role in its day. And it may well have put that amputee, Lt. Nesbit, back together with his father.

While there is no evidence that the father saw the telegram, someone must have come to the son’s aid, because Nesbit survived, became a farmer and a beekeeper in Cherokee County and lived to the ripe age of 83.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured