Despite Southern roots that run deep and a lifelong love of reading, I was unaware of Harry Crews until after his spirit had already left this mortal coil. Perhaps that is not surprising. Growing up, my exposure to books came primarily from suburban English teachers, college professors and my mother, a voracious reader whose interests cast a wide net. But their tastes were probably a bit too refined for the likes of Harry Crews. And he pretty much quit publishing in the late ‘90s, which is about the time I got serious about my reading life.

It wasn’t long after Crews’ death in 2012 from complications of neuropathy at age 76 that I came across a used copy of “Florida Frenzy,” a collection of his essays and fiction published by the University of Florida in 1983. It’s a slim paperback, perfect for reading on the plane, so I took it on a trip and devoured it.

My reaction was, holy mackerel! Here was a bona fide Southern writer in the vein of Flannery O’Connor, whose unvarnished language and absurdist take on life among the lower rungs of the region’s social ladder was shot through with a rough-and-tumble kind of empathy that caught me unawares. How had he escaped my attention?

So, it was with great pleasure that I spent last weekend reading “The Gospel Singer,” one of two books by Crews selected for reissue by Penguin Classics.

Previously out of print, “The Gospel Singer” was Crews’ first novel, written in 1968. It is a darkly funny tragedy about a famous evangelist (his name is never divulged) with long golden hair who travels the country bedding young women and performing at tent revivals. To his dismay, he is being followed from town to town by the “Freak Fair,” a carnival run by a short man with a 27-inch-long foot who proves to be as charismatic as the Gospel Singer but purer of heart.

They are both headed to Enigma, Georgia, a dead-end town on the edge of a swamp and the Gospel Singer’s hometown. Everyone there is in a frenzy to see the prodigal son because they all want something from him. Among them is the Gospel Singer’s old friend, Willalee Bookatree Hull, who’s jailed for the alleged rape and murder of the town’s most desirable young white woman, Mary Bell Carter. Inflamed less by Mary Bell’s murder and more by the belief that a Black man deflowered her, a lynch mob is gathering.

Accompanying the Gospel Singer is his manager Didymus, a monk who is appalled by what he witnesses in Enigma. Although he enables the evangelist’s bad behavior, he also doles out penance and ultimately, in an act of a Biblical nature, sets the novel’s tragedy in motion.

It’s hard to imagine Crews working today, in the age of cancel culture, trigger warnings and masculinity deemed toxic — particularly as a college professor, which he was for many years at the University of Florida. The world he writes about is violent and ruthless, and it’s populated by people with outrageous physical disabilities, wanton women, racists, drunks and the just plain dumb, all of whom are referred to in the most vulgar of terms.

Credit: Penguin Classics

Credit: Penguin Classics

But there’s a point to Crews’ madness, and always present is a throughline of empathy. Perhaps that’s because Crews didn’t hold himself above his characters; he identified with them. The world he grew up in, in the South Georgia town of Alma, was not much different from the worlds he depicted. And his hard-living, hard-drinking way of life was not much different from his characters.

To learn more about his origins, which were as gothic as his fiction, the second book published by Penguin Classics is his memoir, “A Childhood: The Biography of a Place,” with a new foreword by Tobias Wolff, author of “This Boy’s Life: A Memoir.” In addition, Valdosta State University professor Ted Geltner published a terrific biography of Crews called “Blood, Bone and Marrow” in 2017.

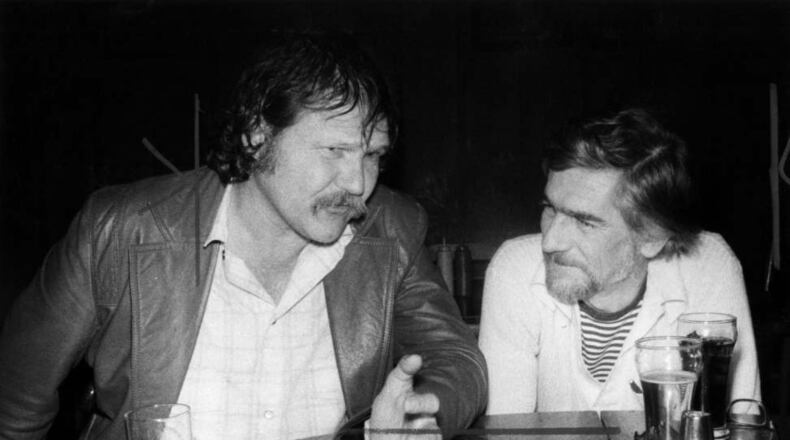

After I finished reading “The Gospel Singer,” I called up AJC book critic Jeff Calder, cofounder of the The Swimming Pool Q’s, because I knew he had studied creative writing with Crews at UF, and I wanted to know what the experience was like.

“I was a senior at the University of Florida, English education student, 1972,” said Calder. “I signed up for his creative writing class. I’d never read any of his books, but I knew who he was. He had a kind of wildish reputation, which was absolutely a recommendation for me.

“He had a shaved a head, a big hoop earring, a Fu Manchu mustache. He was thin and wore these ridiculous frayed bellbottoms and blue Adidas sneakers, and that’s what he wore all the time. He was an unusual looking guy at the time and really stood out.

“If you showed up and turned in a story, it didn’t matter how bad it was, you got an A. If you didn’t even show up at all, you got a B. That was it. That was the ground rules, such as they were.

“Despite being an eccentric character, he was a traditionalist in a lot of ways in his philosophy of writing. He was a good teacher. He was the best teacher I ever had at the university. Always sober and on the mark.

Credit: Penguin

Credit: Penguin

“One of the things that he talked about again and again, was how important it was to get up every day and write. ... And he always said, ‘Never be ashamed of where you come from,’ and that was really important to me because all the books he wrote were about places I knew, places I lived.

“He was extremely funny. He didn’t have that big of a national reputation at that time. It wasn’t until a few years later when he was writing a column for Esquire, that’s when he began to establish his reputation. And I don’t think that was really good for him because celebrity really, I think, encouraged some of his darker angels.”

The reissue of “The Gospel Singer” includes a new foreword by Kevin Wilson, author of “Nothing to See Hear,” who says he was drawn to Crews’ work because he “wanted to know how you leaned into what it meant to be Southern when you weren’t even sure what that meant, exactly.”

He came away from the experience “knowing, on some level, that I wouldn’t ever write like him, could never open the wounds with the kind of ferocity that came only from knowing you’d survive it, because you’d survived much worse,” Wilson writes. “And I remain a fan of Harry Crews because I still don’t know that I’ve read anyone like him.”

Suzanne Van Atten is a book critic and contributing editor for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Contact her at svanatten@ajc.com and follow her on Twitter at @svanatten.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured