Janisse Ray made a big splash with her 1999 literary debut, “Ecology of a Cracker Childhood,” a memoir about growing up in a junkyard in north Florida. It racked up awards, including the American Book Award.

She followed that up with a number of books about nature and the environment, including “Drifting into Darien,” a love letter to the Altamaha River, “The Seed Underground,” about a quiet and steadfast revolution against genetically altered foods, as well as a collection of poetry. Her 2021 essay collection “Wild Spectacle” won the Donald L. Jordan Prize for Literary Excellence.

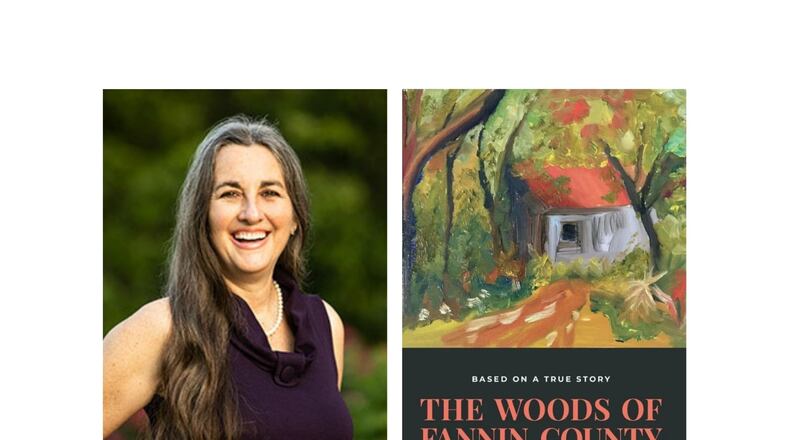

Now she has published her first work of fiction, “The Woods of Fannin County” (Janisse Ray, $19.99). The fictitious telling of a true story, it’s about a family of eight children, ranging in age from 10 to newborn, who, in 1945, were taken to a remote shack in the woods of the North Georgia Mountains and abandoned there to fend for themselves for four years.

Written in Ray’s lyrical, empathetic style, “The Woods of Fannin County” is a harrowing, heartfelt tale of innocence, hope and resilience that considers the true meaning of home. Just 202 pages long, it’s a fast read because it’s so hard to put down.

Ray first heard about the story from her father, who introduced her to one of the surviving siblings. She would eventually interview three other siblings and the wife of another. While the story is true, its central character ― the oldest boy Bobby, who died before Ray heard about the story — is an amalgamation of the siblings she interviewed.

Besides being Ray’s first published work of fiction, “The Woods of Fannin County” is her first foray into self-publishing. Previously published by the likes of Milkweed Editions and UGA Press, Ray didn’t even attempt the traditional publishing route with her newest.

“Why would I?” she asked when I queried her about it on the phone.

“The publishing world is in chaos in so many ways. The way it looks today is not even how it’s going to look five years from now. I think there is a bit of crashing and burning around it.”

While the U.S. Justice Department and Penguin Random House battle in court over whether the publishing company can buy Simon & Schuster, which would officially reduce “the big five” publishing houses to four, Ray raises the rallying cry to “decentralize publishing” and give the power back to the author.

Under the traditional publishing model, Ray said, “the author (is) the creator but making a very small royalty. And the author then, on her or his back, supports this entire middle industry of literary agents, publishing companies, chain book stores, independent bookstores. All that rides on the back of the creator. You can honestly get crushed by that.”

Credit: Milkweed Editions

Credit: Milkweed Editions

On the day we spoke, Ray received queries from two New York presses asking her to blurb their hot new books.

“So much is asked of writers. There’s all the time I spend reading the book, then I have to write four or five glowing lines for the back cover, and what I get is a free copy of the book. No!,” she said sharply. “That’s worth thousands in marketing. And we just ask writers to do this for nothing. It’s almost like writing is a gift economy. I am deeply unnerved by that now.”

In the past, Ray would have been embarrassed to self-publish a book, she said, but she felt like it was the pragmatic thing to do this time.

“When you analyze marketing, you realize the way to market a book now is basically hand-to-hand action,” she said. “You sell books within a community, so if I have the community, what I need to do then is try to enlarge the community of readers for ‘The Woods of Fannin County’ because it is that community that’s going to buy the book.”

But Ray, 60, is a well-established author. What about emerging authors? How do they find an audience through self-publishing?

“I don’t have the answer, but it may not — for a while — involve a printed book.” She points to writers who gain a following on social media by posting videos, poems and other content. “It may look like that. That may be the future.”

How they monetize it, though, she has no idea. “It may be that art is becoming a gift economy.”

Regardless of what the future looks like, “we are still operating under a paradigm of books that doesn’t actually function anymore,” she said. “We have to admit that the old way of publishing is not working.”

To her point, a spokesperson for BookScan, a data service that tracks print book sales in the U.S., recently revealed that 66% of the top 10 publishers’ new books sold less than 1,000 copies over 52 weeks. And less than 2% of new books sold more than 50,000 copies.

During its antitrust trial, a Penguin Random House executive said just 35% of the company’s books are profitable.

“Everything is random in publishing … That’s why we are the Random House,” said Penguin Random House CEO Markus Dohle, according to the New York Times.

Ray likens the current publishing model to a dying oak tree in its last autumn, throwing out a huge mass of acorns. “They’re throwing out so many books, so many of them are 100% crap, and they’re doing it because they know the tree is dying.”

When Ray published her first book to such acclaim in 1999, she thought she was on her way. She was a professional writer whose royalties would sustain her in her old age. She worked every day, publishing seven books, but she’s sitting on six more manuscripts her literary agent either couldn’t sell or wouldn’t try. Despite her talent, her literary awards, her work ethic, her financial rewards have been slim.

“I am radically coming to terms with what my own career looks like from a monetary point of view, and that is not good,” she said.

I suspect more than a few authors will be watching Ray’s self-publishing experiment to see if it might be a viable option for them. Meanwhile, I selfishly hope it is a smashing success because I can’t bear the thought of six Janisse Ray manuscripts languishing in a drawer unpublished.

Suzanne Van Atten is a book critic and contributing editor to The Atlanta Journal Constitution. Contact her at svanatten@ajc.com, and follow her on Twitter at @svanatten.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured