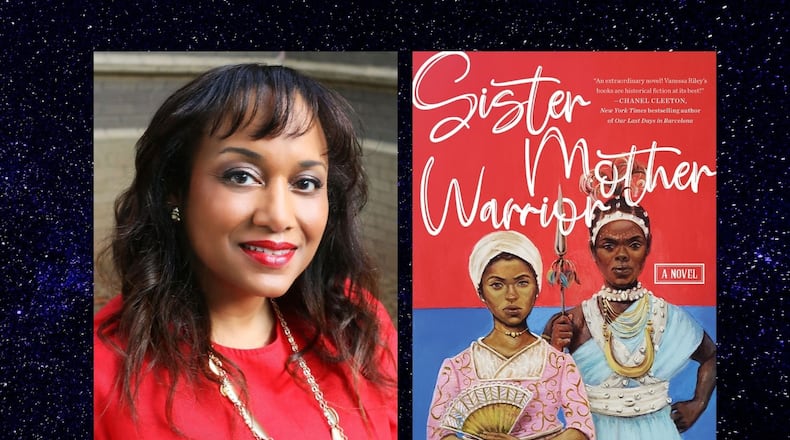

“Sister Mother Warrior” by Georgia author Vanessa Riley is a fictionalized account of the 18th century Haitian Revolution told through the two women who loved and supported the first emperor of Haiti, Jean-Jacques Dessalines. This sweeping epic encompasses the lives of Dessalines’ mother Toya, a Dahomey warrior who was sold into slavery, and his wife Marie-Claire, a freeborn woman of color, as they battle French, Spanish and British colonialism to establish the first country to abolish slavery.

In the author’s note, Riley states that separating fact from legend proved challenging while researching the Haitian Revolution. History is written by the victors, and she encountered a bevy of competing narratives promoting the agendas of different factions. Employing a creative license, Riley decided to embrace these contradictions and portray a variety of viewpoints through the eyes of different characters, most based on or composites of historical people.

The result is an ambitious, if sometimes dizzying, telling of the tempestuous battle against early Haitian colorism and slavery. Prose laden with vivid world building and detailed military strategy, combined with Riley’s zeal for historical accuracy, contribute to a dense reading experience. Four different languages and two alphabets appear in the narrative, and multiple names are used to refer to the same characters depending on who is speaking in what language. For the modern reader, each line leaves a lot to unpack.

“Sister Mother Warrior” begins in the West African Kingdom of Dahomey in 1750. Toya’s village is conquered, and she’s selected by the king for Minos — his royal guard of female warriors. After nearly a decade, she becomes their fierce and powerful leader but is betrayed by one of her own, sold to the French and enslaved on the Cormier Habitation on Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti).

Toya eventually rises in prominence and becomes the caretaker for the habitation’s children. She takes a special interest in one of them, Jean-Jacques, an indirect descendent of her Dahomey king. He becomes her hope for the fulfillment of a prophecy of freedom her gods have foretold.

But Toya is haunted. Minos warriors played an integral role in helping the Dahomey king sell conquered people into slavery. Fraught with guilt, she pays her penance by training the laborers on Cormier Habitation to one day overthrow their oppressors. It does little to assuage her burden while she waits for their chance. Rebuking a compliment from her overseer regarding her success and resilience, Toya says, “Not resilient. Persistent. We persist against the perils. There’s a difference.”

Revolution is roiling under the surface and has been for decades. The enslaved are poisoning the Blancs — their cruel masters — and provoking gruesome, public punishments. While the French and Spanish battle for control of the island, bloodshed and poverty abound. Freedom is defined by strict classifications based on the shade of a person’s skin. Affranchi, the mixed and Black caste, hold a fraction of the rights of the Blancs and fight among themselves for power. The layers of oppression, which Riley expands upon from a myriad of angles, are ready to implode.

Meanwhile, young Jean-Jacques discovers a kindred spirit in Marie-Claire, a privileged and precocious do-gooder obsessed with feeding the poor. Although a free woman, she’s forced to straddle a delicate balance of invisibility and respectability to conduct her daily life as the city of Cap-Français boils over. They fall in love, but Jean-Jacques isn’t free yet, so they cannot marry. This forced division results in their separation and reunification numerous times over the years.

At times, Riley’s loaded prose makes it difficult to emotionally connect to her characters, leaving little room for the nuance required to convey motivation. In one scene, Marie-Claire expresses shock at hearing her mother say a kindness about her grandmother: “My ears almost exploded like cannons, pounding and jolting my spine.” In the next line, she denies caring about “old feuds,” and then the topic is dropped. It’s one of many abrupt interjections threaded throughout that raise questions without contributing to the momentum of the story.

In fulfillment of Toya’s prophecy, Jean-Jacques does rise up to lead his people to form a self-governed democracy. Riley’s narrative explores the cost Toya and Marie-Claire pay while aiding in his years of revolution. Both are remarkably strong, driven women who contribute to the cause and are easy to root for, especially because they are complex and morally textured on their own.

Marie-Claire chooses herself over Jean-Jacques multiple times throughout their love story — usually to his consequence. She’s very much a woman who wants it all and refuses to subjugate herself. But once she’s the mother of his many children, Marie-Claire’s commitment to her autonomy serves her family well. Becoming the first empress of Haiti doesn’t happen without sacrifice. A lifetime immersed in war and spent loving a man who is away for a decade leading the fight takes its toll on them both.

Riley’s storytelling skills shine through, creating a compelling portrayal of two women who remain true to themselves under tremendous hardship. If only the novel focused more on their emotional perseverance set against the backdrop of the Haitian Revolution, not the other way around. Still, “Sister Mother Warrior” is an impeccably researched, powerfully reimagined tale of sacrifice and success, love and selfishness, and war and independence as experienced by the women behind the man who liberated Haiti from slavery.

FICTION

by Vanessa Riley

William Morrow

480 pages, $27.99

About the Author

The Latest

Featured