Pete Correll, longtime Georgia business leader and philanthropist, dies at 80

A.D. “Pete” Correll learned as a child to solve grown-up problems and built on those skills to become a go-to guy in corporate board rooms, the city of Atlanta and even the White House.

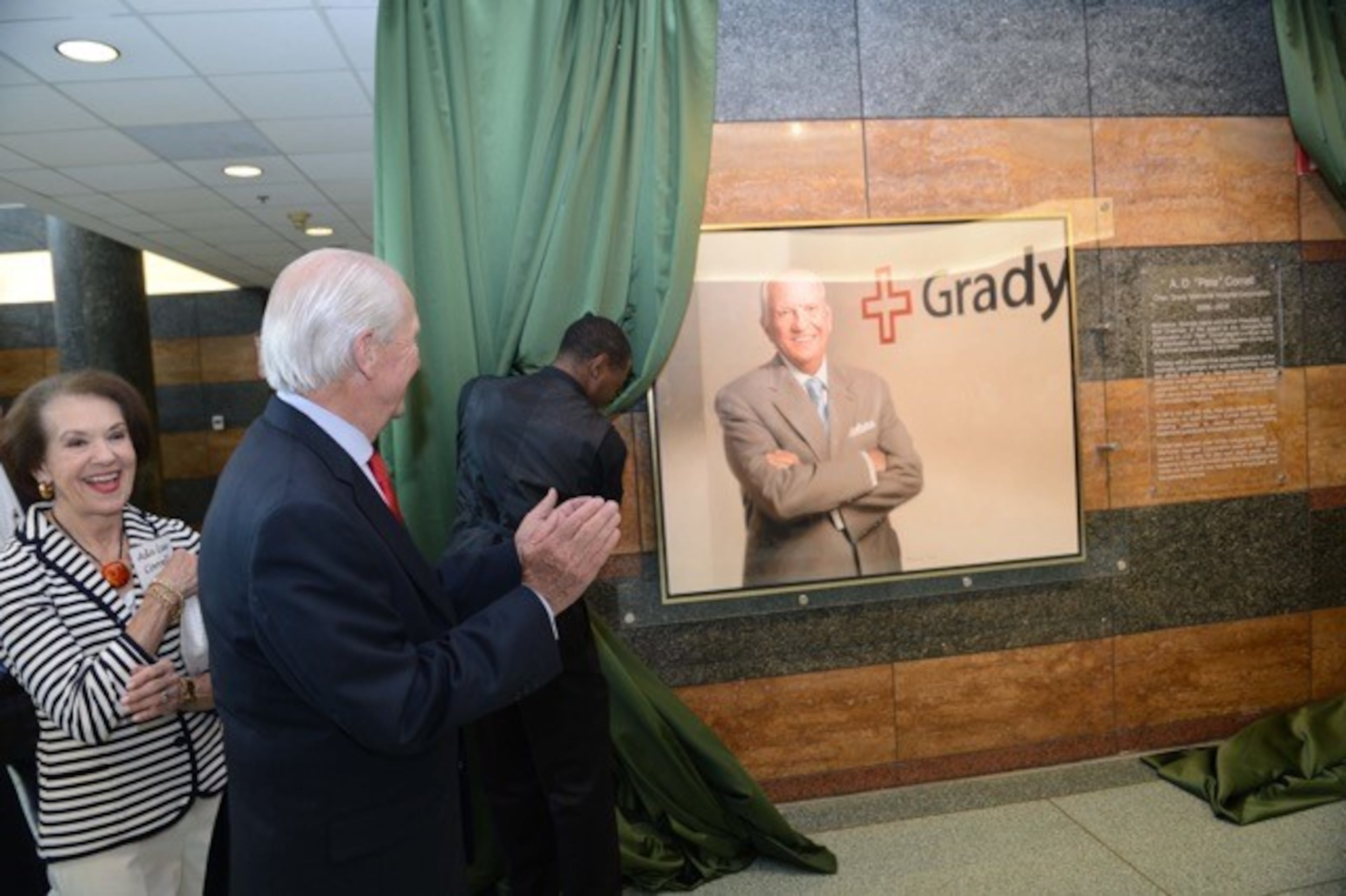

He was a moving force in the rescue of the financially failing Grady Memorial Hospital, was cited by President Bill Clinton in 1995 for lessons learned from him when he was governor of Arkansas about doing well and doing right. Correll led Georgia-Pacific and was a philanthropist who left fingerprints around the state. He was called on by mayors, business leaders, and friends for help for a particular reason.

“He was a guy who got things done,” said Tom Bell, a longtime civic and business leader who befriended Correll 30 years ago.

Correll co-chaired a commission in 2003 that renamed Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport to honor Maynard Jackson, the city’s first Black mayor. He served on the Georgia Aquarium board and gave money to numerous causes in Brunswick, where he grew up. He and his wife, Ada Lee, both University of Georgia graduates, gave $5 million to their alma mater three years ago to start a scholarship for students with significant financial need.

He died Tuesday from kidney failure, his family said. He recently turned 80.

Correll was 12 when his dad died, leaving his wife to run the struggling men’s store he owned. Correll helped, learning much about business and tough choices before heading off to the University of Georgia and then earning two master’s degrees on scholarship at the University of Maine.

After graduating, he crisscrossed the country working in paper mills before joining Georgia-Pacific in 1988. Correll became chairman and CEO in 1993 and made it into a powerhouse. He negotiated a $21 billion sale of the company to Koch Industries in 2006.

Correll’s daughter, Elizabeth Correll Richards, said her dad believed in fixing problems and was unafraid of controversy.

“He would run into the storm,” she said.

Correll did exactly that when he and Bell met for drinks and talked about Grady’s financial problems, which some feared would cause the city’s public hospital to close. After a couple of drinks, they decided to help resuscitate the hospital mired in debt and mismanagement. They built a case and coalition of business, civic and government leaders and began work after winning the backing of the Fulton-DeKalb Hospital Authority.

The most challenging part, his daughter said, was navigating the racial politics. Some Black community leaders, questioned Correll’s motives.

“Pete was willing to step into the fire like that,” recalled Michael Russell, a Black Atlanta real estate executive recruited for help by Correll and Bell. At heated community meetings, “We all would have to answer questions,” Russell said. “But Pete was the leader. He was the guy who was out front. He was the guy taking most of the arrows.”

The Rev. Tim McDonald, pastor of First Iconium Baptist Church and founder of the African American Ministers Leadership Council, started leading the charge against the Grady “privatization,” as they called it.

“I didn’t trust any of them, to be honest,” McDonald said of the larger group.

But Correll’s demeanor, honesty and willingness to face their questions changed his mind.

Correll made the case to the business community that it wouldn’t serve Atlanta to have no hospital serving Grady’s public mission; that those patients would wind up crowding other emergency rooms and Atlanta would take a blow to its reputation. He also conveyed the Grady Coalition’s concerns to the business community, McDonald said, making sure people would not be turned away for failure to pay co-pays on services or prescriptions. McDonald called Correll “a bridge-builder.”

“He and I had lunch and broke bread together,” McDonald said.

John Haupert, CEO of Grady Memorial Hospital, said the work led Grady’s transformation from a seriously underequipped facility into a thriving modern hospital: both as a national leader in trauma care and a continuing safety net hospital that cares for Atlanta’s poor.

After new management came in, Haupert said, the first year the hospital brought in $100 million in new revenue.

It began to rebuild community support and attract donations for state-of-the-art technology, systems and expansions, which probably total $500 million in private philanthropy at this point, Haupert said.

The Saving Grady Task Force helped raise $325 million that has since been invested in new facilities and services including the Correll Cardiac Center.

Correll told his secret to success in a 2014 talk at Kennesaw State University.

“I had always had a very simple premise in my life that I might not be smarter than anybody else, but I can outwork anybody,” he said.

Correll is survived by his wife of 58 years, Ada Lee, Richards, his daughter, Elizabeth, his son, Alston, and five grandchildren.

A service will be held at First Presbyterian Church in Atlanta, Wednesday, June 2 at 2 p.m.