Dr. Mill Etienne is chief of neurology at a community hospital and an associate professor of neurology and medicine and vice chancellor for diversity and inclusion at New York Medical College. A graduate of two Ivy league schools, Etienne has mentored numerous Black and Hispanic students who have studied at all the Ivy league schools as well as many of the other schools with competitive admissions.

In a guest column, Etienne discusses the potential health care challenges faced by underserved communities after the elimination of affirmative action by the U.S. Supreme Court and offers investment strategies to enhance the pipeline of students to become medical providers in the underserved communities.

By Mill Etienne

Two Ivies are in the spotlight this summer: Harvard, with its devastating loss at the U.S. Supreme Court; and Blue Ivy, Beyoncé's 11-year-old daughter, performing on stage alongside her mother. These two events are jangling in my mind as a Black, Ivy-educated doctor, because the investments we make in our young people now have enormous consequences for the health of our communities for generations to come.

Although much of the recent focus has been on how the court’s decision will reshape Harvard, I know it will directly impact admissions at other schools with competitive admissions. As a physician and neurologist, I am particularly concerned about how this decision will impact access to care, including the specialized services I offer as a neurologist.

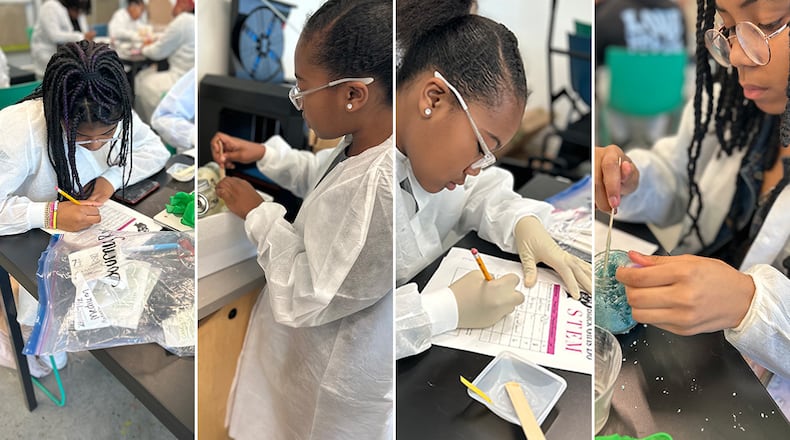

Credit: William Taufic

Credit: William Taufic

According to the most recent U.S. census, Black and Hispanic people make up 32.8% of the country’s population but account for 10% of neurologists. This low representation is not new and, sadly, after this recent Supreme Court decision, it may get worse. Diversity in the health care workforce matters and is critical to addressing the myriad of health inequities we now face in our society.

When I think about affirmative action, I think not only about how I or other individuals may have benefited, but also more importantly about the exponential impact affirmative action has on uplifting the health of underserved communities.

When I was 11 — Blue Ivy’s age — I knew I wanted to be a doctor. At least that is what I told my classmates when we were sitting in the cafeteria discussing our aspirations. I still remember how despondent I became when one of my fellow fifth graders told me, “There are no Black doctors.” I boldly responded by speaking about a doctor I had seen multiple times on television. He and the other students started laughing and condescendingly indicated that the doctor I referenced was not a real doctor.

I recall the doubt in my mind and how small I felt. How could I have been so foolish and why was I not able to come up with another Black doctor, one who was real? I had been raised by my parents to believe that if I worked hard in school, I could do anything. Was this not true for people who looked like me?

At that time, I did not know the statistics regarding the low numbers of Black physicians in America, the worse health outcomes experienced by Black patients, and had no real grasp of what race was and most certainly had not considered the role race would play in my career prospects until that student threw it in my face.

Despite discouragement throughout my journey, I completed my undergraduate studies at Yale University, and earned a medical degree from New York Medical College and a master’s in public health from Columbia University, where I had a perfect grade-point average. I became a neurologist and now serve as the chief of neurology at the community hospital in the small town where I grew up, and it gives me great pleasure to serve the patients in my community, many of whom are Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.

To be clear, I strongly believe that when it comes to recruiting students and medical providers, it is important to get the best possible candidates into your institution and into the communities to provide high-quality care to the patients. I also believe in evidence-based medicine and doing what is best for our country and our community. That is why, given the compelling evidence that has demonstrated the value of having Black and Hispanic physicians available to care for these underserved communities, any measure that could decrease their numbers could threaten the overall health of America.

But a serious commitment to correct this gap in the representation of doctors and the representativeness of people receiving care will take a serious dedication of resources. But I know that we can do it if we commit to it. A few years of sustained, intense and exponential investment brought Americans to the moon in the mid-20th century — what if we took the representation gap as seriously as a moonshot?

Closing the representation gap will require investment in K-12 education, including robust pipeline programs in underserved communities with diverse role models so that young people can see what is possible for them regardless of their identity. It will also require investment in opportunities for medical providers to work in underserved communities, and in low-resource communities to increase access to fresh food and access to space that allows them to be physically active if they are able.

Finally, we’ll need to invest in partnerships with communities to explore the challenges they face to achieve optimal health and then instituting a plan that works for each individual community. This includes hiring from the community, so they have a say in how and what type of health care is provided.

This list is not exhaustive, but is a reasonable starting point that demonstrates the value of sustained investment in communities to narrow the representation gap and challenge existing and emerging health disparities. Similar investments in cancer and HIV have seen transformative results, which should give us hope that we can do this.

Blue Ivy likely will not be leaving the spotlight any time soon, and neither will the many schools impacted by the recent Supreme Court affirmative action decision. If an 11-year-old can demonstrate such brilliance and mastery on the stage, surely the adults in the room can come together and work toward the moonshot of eliminating health disparities in the United States.

We have all heard the proverb that “It takes a village to raise a child.” Now when I consider Blue Ivy and her generation’s example, I believe “it takes a child to raise a village” is more fitting.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured