Mark Bauerlein is a professor emeritus of English at Emory University and an editor at First Things magazine. In a prior guest column, Bauerlein critiqued the state’s proposed new standards to guide the teaching of English language arts in the state’s public schools.

In this new column, he is more optimistic about the revisions made, including an emphasis on student recitation.

By Mark Bauerlein

In my many years teaching literature at Emory University, one assignment I gave was particularly unappealing. On Friday, I would announce, students had to select a poem at least 10 lines long, memorize it over the weekend, and recite it in class on Monday. Anguish followed, some grumbling, a few sighs. They hated it. These were smart kids, ambitious and diligent, but learning verse by heart and performing for others didn’t jibe with the pre-med, pre-law, and business focus that predominates among Emory undergrads. For all their talents, they knew that they weren’t very good at it.

On Monday, though, the attitude had changed. One by one, students took their turns, coming to the podium with a nervous smile, a bit hesitant. As they proceeded from line to line, sometimes pausing to concentrate on the next word, occasionally needing a syllable of help, their voices grew stronger, their posture straighter. When they ended and the rest clapped, the performer grinned and marched back to their seat, relieved and gratified. I could see the pride glowing. Our speakers knew they had accomplished something, gutted it out in front of peers. Years later, I am sure that each student who did it remembers it with satisfaction.

Credit: Contributed

Credit: Contributed

Elder Americans did this kind of thing a lot in middle and high school, before a certain philosophy of learning downgraded it to “rote memorization,” a deadening mechanical exercise. From there, recitation disappeared from the classroom as learning standards turned to modes of thinking presumably higher than memory tasks (e.g., analysis).

I never bought the idea that memorizing a poem, soliloquy or speech was so crude an action. It didn’t match the mental labor I witnessed at Emory. So, when the Georgia Department of Education asked me for input on the new English language arts standards, I set recitation high among the recommendations.

And now, remarkably and wonderfully, the exercise is back. The Department of Education has just released the latest version of English language arts standards for public comment, and it includes this chore, which runs from early grades through high school:

Build background knowledge by reciting all or part of significant poems and speeches as appropriate by grade level.

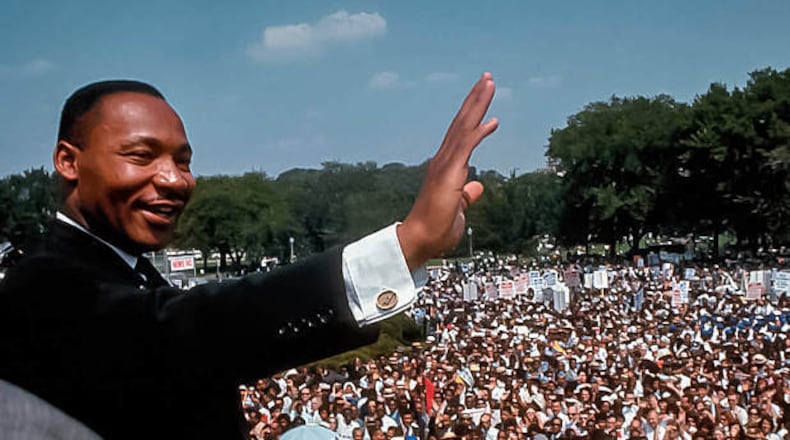

This is fantastic. The standard appears as a “presentation” skill, a type of oratory markedly missing in teen-speak, while the words “background knowledge” and “significant” ensure that students will learn important history and literature when they memorize their texts. Every year, students will have a rich recitation task before them, learning by heart the words of an Emily Dickinson or Wordsworth poem, a good portion of “I Have a Dream” or George Washington’s Farewell Address, or a soliloquy in “Julius Caesar.” After 12 years, public school students will have the words of Lincoln, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Shakespeare, Congressman John Lewis, Tennyson ... permanently in their heads.

Let’s be clear, too, that much more than robotic recall happens when an eighth grader gets the words of “Paul Revere’s Ride” exactly right. The brain shifts into high gear, as neuroscientific studies show. She learns words that never come up in her social media, and she has to pronounce them well in front of an audience. (The public speaking side will serve her nicely in any number of workplaces she occupies later on.) She has to “become” someone else, too, to adopt another voice, get out of her own head and imagine another’s experience, mood, outlook — a crucial activity that builds cognitive empathy.

The whole thing is a complex cognitive process, as is obvious when we see students struggle with it and stand tall when they’re done. Genuine learning takes place when short-term retention turns into long-term memory, and recitation is one of the surest ways to make it happen.

What the Georgia DOE has done for young Georgians will benefit them for the rest of their lives, not just in college when they have hundreds of facts, formulas, laws and nomenclature to memorize and they find that their literary workouts in the past have prepared them well (memory is a muscle — work it and it develops), but in later times, too, when they face joys and hardships with the best words of the best writers and speakers echoing in their minds and offering wisdom and eloquence, precisely what their screen-fixated, media-immersed, peer-pressured lives preempt and forbid.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured