Opinion: More resources, not police, will make schools safer, stronger

In a guest column, former Cobb County school board member Charisse Davis and Cobb student Marli English, a leader of the Georgia Youth Justice Coalition, say school safety cannot solely depend on more police and armed guards. The pair say the key is adding services that improve the lives and mental health of students.

Both Davis and English are members of the Race Forward H.E.A.L. (Honest Education Action & Leadership) Together initiative that supports equity and racial justice and a fully funded, inclusive public education system. English is a high school senior in Cobb. An educator and media specialist, Davis served one term on the Cobb school board before choosing not to seek reelection last year.

By Charisse Davis and Marli English

What does safety in our schools really mean? Five years after the school shooting in Parkland, Florida, left 17 people dead and caused dozens of injuries, we’re still asking ourselves that question.

And we’re still coming up short on solutions.

For us, a former Georgia school board member and a current student, this is more than theoretical. This is part of our lived experience.

Since Parkland, we’ve learned that while the conversation about student safety may start with guns, it doesn’t end there: To be truly secure, students need nourishing food, classrooms with proper heating, access to books and supplies and health services that sustain body and spirit.

The tragedy in Uvalde, Texas, last year and the recent story of a 6-year-old shooting his teacher in Virginia make it clear that some of these disasters could be caught before they happen if we consider the comprehensive well-being of our children as part of the safety net.

Of course, keeping guns out of our schools is critical. Just a few months ago, a high school student in our neighboring Gwinnett County was shot and killed near campus. However, one of the primary lessons emerging from these traumas is that responses focused on arming teachers and hyper-policing are misguided and ineffective.

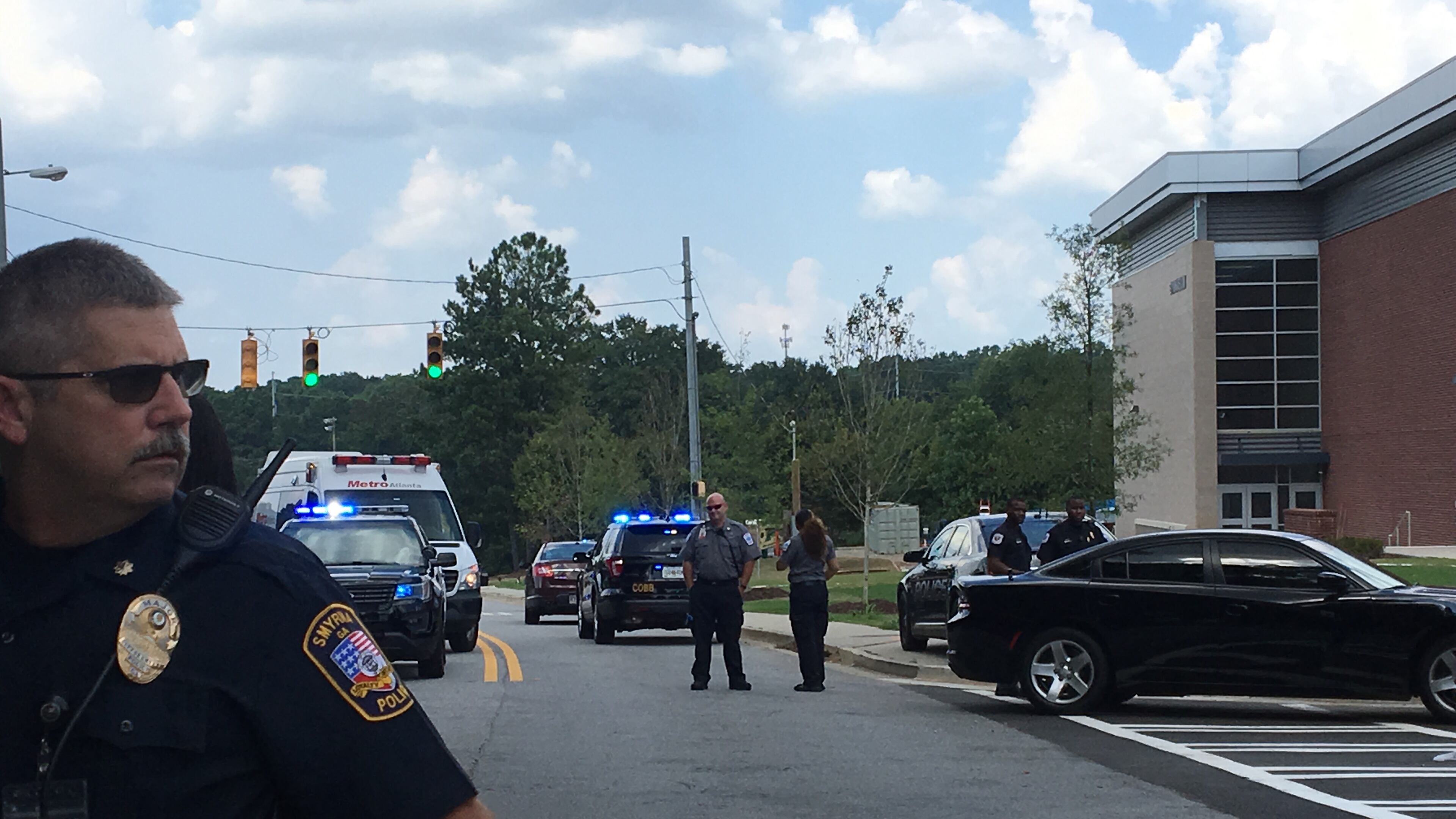

The increased surveillance and police presence — more than $3 billion spent by districts across the country every year — have not decreased school shootings. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the percentage of public schools reporting the use of security cameras increased 30 points between 2010 and 2020; the percentage of schools with armed security staff on campus at least once a week, such as security guards and police officers, increased from 43% to 65%. Yet, the incidences of school shootings with casualties have only continued to rise.

Moreover, the sharp increase in police and armed guards in our schools is especially dangerous to Black students and other students of color, who are often the first (and only) students to be targeted by aggressive police tactics. Rather than making all students feel secure, it has increased the sense of inequity and fear in those students most likely to be racially profiled by law enforcement.

Students need wraparound services and public support after being traumatized by the consequences of COVID-19, increased surveillance and the near-constant chatter of active shooter preparedness. We were heartbroken to hear that a student in our district was found frantically searching for scissors after an active shooter alarm malfunctioned in her school.

These anxieties are layered on lives that are already in the crosshairs of systemic failure. In 2020, on any given day, more than 35,000 Georgia children experienced homelessness and more than 1 in 6 were food insecure. During the pandemic, the federal government funded free breakfasts and lunches, ensuring that children would have some basic nutritional security. With the expiration of federal dollars, state and local school systems have to choose between incurring debt and feeding their kids.

The gaps in mental health services are equally troubling. According to a study published in Pediatrics in 2020, one in four teenagers have had passive suicidal thoughts and one in 10 have had serious ideations with a plan to complete. Yet, we have an acute shortage of professional counselors to help them.

While elected officials argue about better gun regulation, we can redefine the vision of school safety to encompass the full reality of students’ lives and challenges. Here is what we believe we ought to do to achieve that vision:

Call on state officials to continue free breakfast and lunch programs.

Fully fund robust physical and mental health programs in our schools. In October, the U.S. Department of Education announced grant programs totaling $280 million to increase access to mental health services for students, by expanding the number of credentialed school-based mental health professionals. This investment is a good place to start, but we need to be proactive here in Georgia.

Focus attention and resources on safety methods like restorative practice and peer-led mentoring to de-escalate and resolve conflict without violence.

Train educators, staff and appropriate volunteers to serve as advisers and confidantes, to whom students can turn at times of anxiety or crisis.

Create ways for students to be heard and heeded in formulating and implementing solutions, so that they know that their voices and lives really do matter.

The gaps in mental health services are equally troubling. According to a study published in Pediatrics in 2020, 1 in 4 teenagers have had passive suicidal thoughts and 1 in 10 have had serious ideations with a plan to complete. Yet, we have an acute shortage of professional counselors to help them.

It’s not just our duty, but our honor to let our students know that — as individuals, as communities and as institutions — we truly care about their well-being, that we believe in them and want them to succeed. That necessitates not just words, but actions, and the funding to make it happen. We know that safety doesn’t come from a gun — it comes from the dedicated attention and resources that young people need to feel secure enough to thrive.