We’ve talked a lot about the disruption to K-12 public schools from the pandemic, but not nearly enough about the upending of preschool and pre-K, which could have even longer lasting ramifications for student success.

Researchers such as neuroscientist Philip A. Fisher have shown how early stress on neurobiological systems undermines healthy brain development. A professor of psychology at the University of Oregon, where he directs the Center for Translational Neuroscience, Fisher joined a web panel today to discuss a new report on how COVID-19 impacted young children’s education.

The Education Policy Initiative at the University of Michigan Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, the Urban Institute, and early childhood experts at nine other institutions undertook a review and synthesis of the 76 most high-quality studies on the COVID impact, spanning 16 national studies, 45 studies in 31 states, and 15 local studies. Two or more of those studies included Georgia data.

Among the conclusions of the report, “Historic Crisis, Historic Opportunity: Using Evidence to Mitigate the Effects of the COVID-19 Crisis on Young Children and Early Care and Education Programs”:

Young children's learning and development suffered setbacks during the crisis.

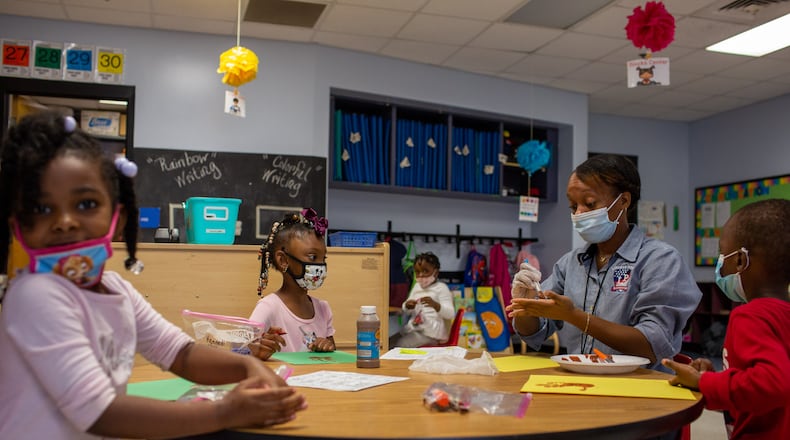

Safety-driven changes to the learning environments of young kids didn't foster their academic or social-emotional development.

Children of color, dual language learners, and children from families with low incomes appear to have been more negatively affected.

Remote/hybrid learning was challenging for children, families, and teachers and resulted in significantly less learning time and lower-quality instruction.

“Some changes that had to be done weren’t conducive to learning,” said study co-author Christina Weiland. She said hybrid and remote learning was less effective with younger students and often meant less instructional time. A Louisiana survey cited in the report found early childhood teachers spending a median of about five hours per week interacting with remote learners.

“The crisis also added immense challenges and stress for early educators — including fears about getting sick, increased financial stress, and the additional work to enhance safety in in-person settings and to adapt to remote learning,” said Weiland.

While there is limited hard data on how COVID affected educational outcomes, “What we do have is not good news,” said Weiland.

Results of direct assessments revealed young children did not make the same progress in critical early reading skills that they did pre-pandemic. Setbacks were largest for Black and Latino students.

What this means, said Weiland, is that children will enter school with a wider range of developmental levels, creating challenges for teachers to meet everyone’s needs and reach grade-level benchmarks.

Neither the report nor the panel today was all doom and gloom. The Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan includes the largest public investment in child care in U.S. history, $39 billion. It also allotted $122 billion in relief for K-12 schools.

That investment ought to pay for proven interventions, including making the most of the next several summers to address gaps, tutoring as early as kindergarten; and hiring assistant teachers to work with small groups, said Weiland.

While the pandemic affected the lives of all children, those with supportive and nurturing adults in their lives were more insulated. The research shows those kids, despite the ups and downs, will be relatively OK, said Fisher, whose lab has been conducting ongoing surveys since April 2020, known as the RAPID-EC project, with a national representative sample of parents and caregivers about their experience during the pandemic.

At the greatest risk of falling behind are young children in homes that suffered more from COVID, where money was tight, and harried parents were unable to provide stability and support. The sooner those families regain their economic footing — and the federal stimulus checks already have alleviated some of those stressors — the better off children will be, said Fisher.

“One of the big surprises in our data was that not only were children relying more on parents for emotional support, but their young children were also a big source of emotional support to parents,” said Fisher. Pre-pandemic, parents often cited friends and co-workers as their emotional bulwarks, he said.

“We really saw the ties that bind having made a big difference in the context of the pandemic, despite the many challenges people were facing,” he said. “As we have seen material hardships ease as more aid becomes available, we’ve seen levels of hardship begin to drop. People are doing better emotionally as the money being allocated makes it into their hands.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured