First-year teachers begin careers amid coronavirus pandemic

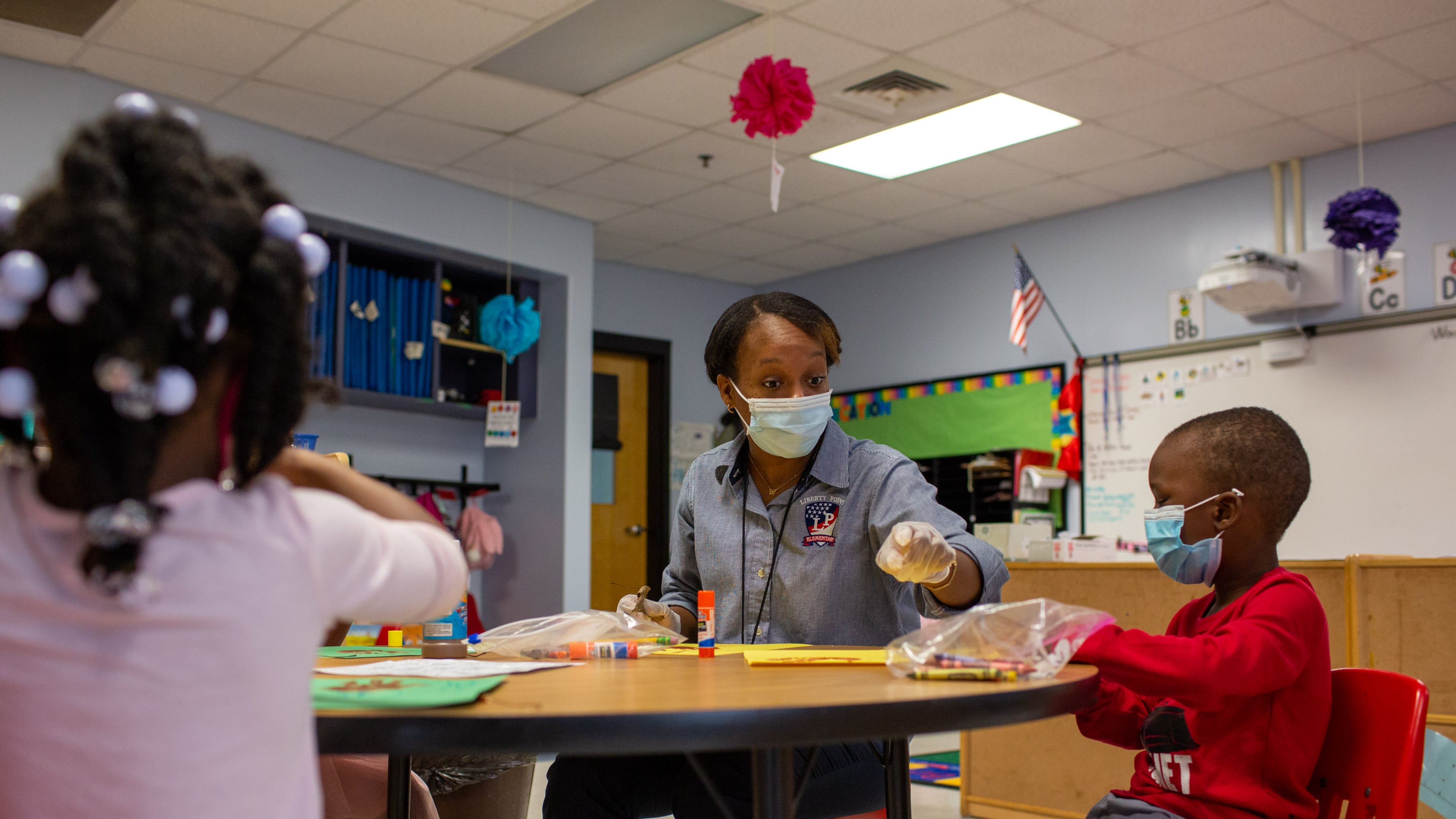

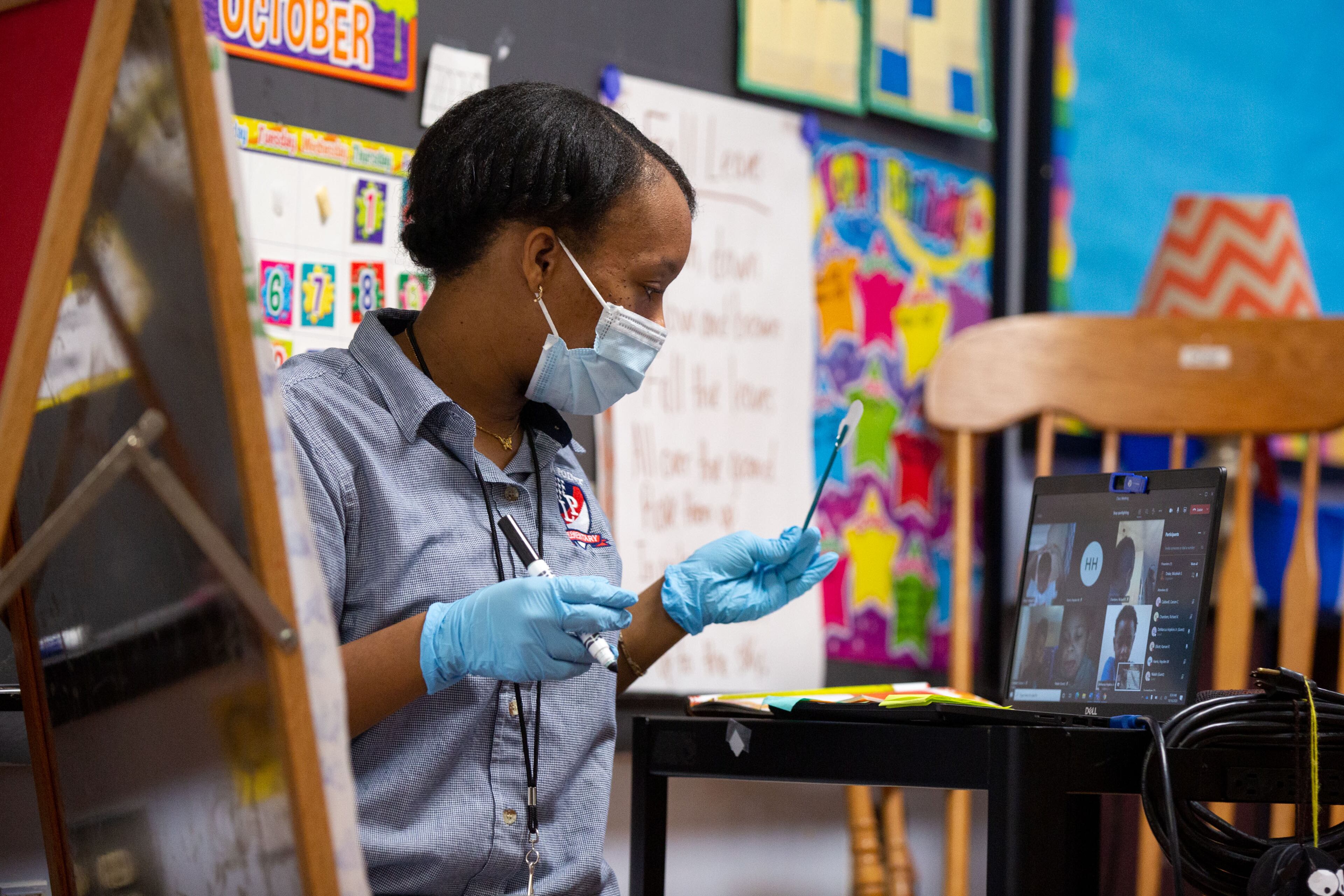

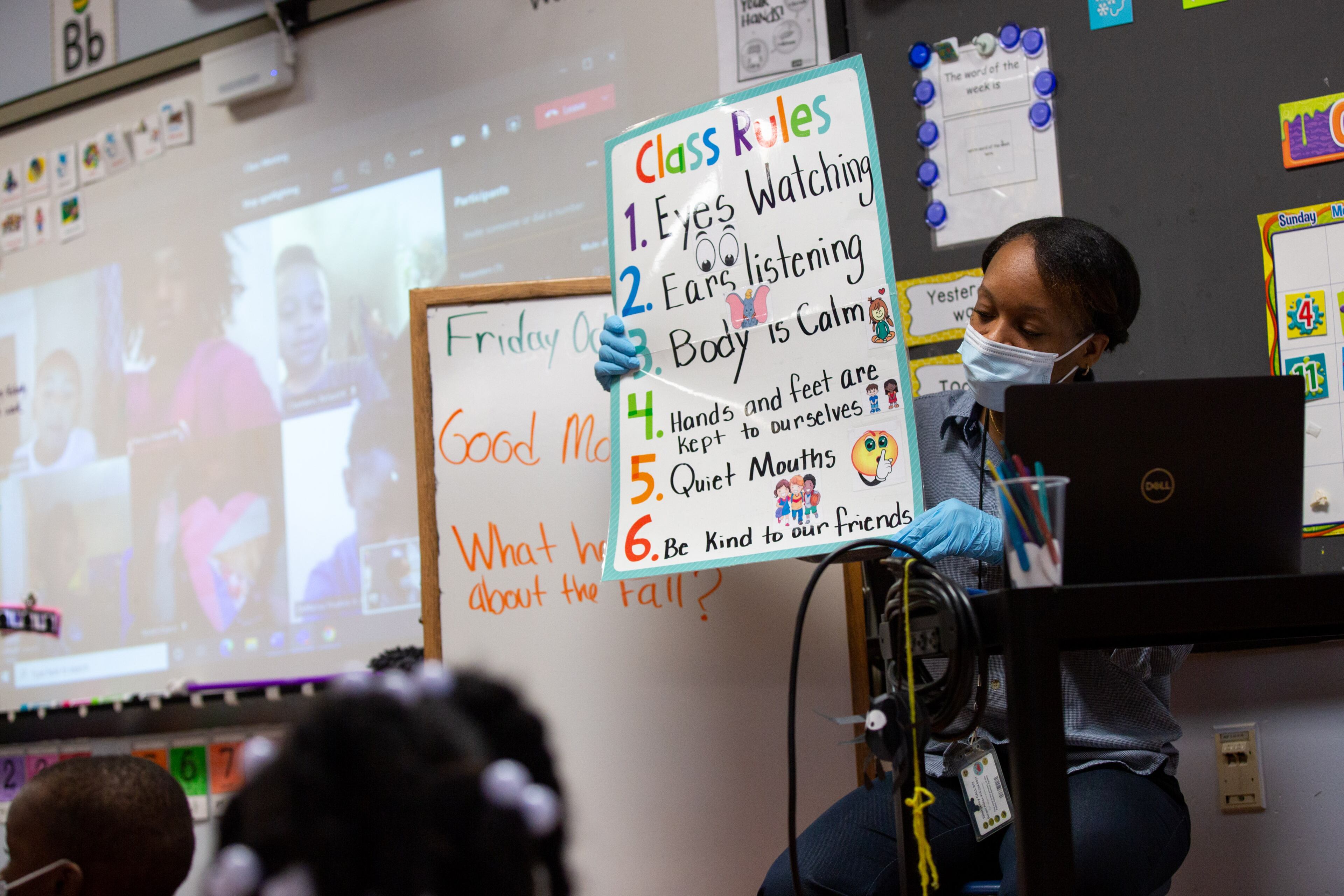

“See you Monday morning” is a common farewell from teachers to students at the end of the school week on Fridays. For Micahiah Drake, this phrase came at 8:45 a.m. on a recent Friday as she waved at her laptop to the six students whose faces were projected on the board behind her. For those virtual learners, their time with the teacher was done for the day. On the other side of the screen, six more students sat on the carpet in front of Drake; the rest of their in-person learning day was still to come.

Drake is a prekindergarten teacher at Liberty Point Elementary School in Fulton County. While she started as a substitute teacher and worked as a paraprofessional for a few years, this is her first year as a pre-K teacher. Out of 14 students, she is teaching eight online and six face-to-face amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Schools closed their doors in March, shifting to remote learning. Some districts have brought students back into buildings this fall; others have remained online. For first-year teachers — who may be fresh out of student teaching in college or who came to teaching from other career paths — as well as experienced teachers, the pandemic has thrust them into a new teaching environment.

Andi Bishop, a first-year seventh grade social studies teacher at Jasper County Middle School, graduated from Georgia College & State University in May. She was in her final semester of student teaching when the pandemic closed schools in the spring.

“I didn’t hardly do anything for student teaching after that, not that my program didn’t require me to, my partner teacher was so busy and overwhelmed he just couldn’t ... find a way to incorporate me into it. He didn’t really know what he was doing and so he couldn’t really tell me what to do,” Bishop said.

Lillie Jackson, a first-year seventh grade science teacher at Crabapple Middle School in Fulton County, was learning to teach her own lessons as a student teacher before the pandemic.

“When the pandemic hit, in the county I was in (Barrow County), they weren’t meeting with their students over Zoom or anything like that. They just started sending them work, and so from my end there wasn’t a ton that I got to do or contribute to just because it was basically chaotic for everyone,” Jackson said.

Things were just as abrupt for Peter Waltz, a first-year seventh grade English-language arts teacher at Richmond Hill Middle School in Bryan County. He was finishing up student teaching for his master’s degree at the University of Georgia.

“I told the kids, ‘You know I’m going on spring break for this week but I’ll see you guys next Monday,’ and I never came back,” Waltz said.

As schools adjusted reopening plans this fall to keep up with COVID-19 guidelines, new teachers had to adjust their expectations.

Bishop was originally supposed to teach two classes face-to-face and two virtually, but instead teaches about 80 students face-to-face after swapping with another teacher.

“I’ve honestly been so surprised as to how well everything is going and how normal that we’ve made it,” Bishop said.

Jackson credits an extra week of preplanning and training for helping her prepare for the early phases of the semester, which were fully remote. About 60% of Fulton County’s 95,000 students are back in classrooms now since buildings finished reopening Oct. 14, district officials said.

At Richmond Hill, teachers are moving between classrooms rather than students changing classes. Waltz initially had two face-to-face classes and two virtual, with an in-person homeroom class, but the homeroom was later converted to a virtual homeroom due to the high volume of virtual students.

“Now I don’t even get kids in my classroom anymore, which is sad because I decked out the room for it and everything for it, but it’s kind of nice in the same vein,” Waltz said.

‘It’s a lot’

In addition to traditional first-year teaching hurdles, the pandemic has added other challenges like new teaching formats and students who lack access to technology.

“Every teacher right now is having to work hard, but I know that new teachers are having to work even harder to think about how to actually set up a lesson, manage a lesson, assess a lesson and then build the relationships at the same time while being a technology expert. It’s a lot,” said Philip Peavy, co-department chair of career and technical education at Paul Duke STEM High School in Gwinnett.

One challenge across grade levels is classroom management and engaging students.

"I think that (students have) kind of ... lost their way a little bit and it’s taken a while to get them back used to being in school and knowing their expectations,” Bishop said.

In the Clarke County school district, teachers received extra weeks of preplanning when the start of the school year was pushed back to after Labor Day. That time helped Jose Cleveland, a first-year fourth grade teacher at Chase Street Elementary School. She graduated from UGA in December and currently teaches about 15 students virtually from her classroom. The district is set to start bringing students back to schools Nov. 9.

“I have this feeling sometimes that my degree that I earned less than a year ago is worth nothing at this point because my challenges when I was student teaching are very different than they are now,” Cleveland said.

Now, it’s things like whether students are actually working when their cameras are off and making sure they don’t play games during class, she said.

‘Unity in the chaos’

During this time, relationships between new and experienced teachers are more important than ever.

Corneil Jones, a curriculum support teacher and induction adviser at Liberty Point, works with teachers there and as a virtual coach to teachers across the district.

“The differences in what you learned in college learning to teach and actually having a classroom of your own that you’re responsible for, I think that sometimes can make or break people and it’s the support that they receive or the mentorship they get that helps them either succeed or feel like they need to drop out,” Jones said.

About 8% of the teaching workforce leaves the profession each year, according to a recent report by the Southern Regional Education Board, a research and consulting organization for Georgia and 15 other states. With low pay and the combined difficulties of teaching during a pandemic, there is concern even more teachers could leave their jobs.

The bright spot in all of this: Everyone is facing this difficult situation together.

“It might be a good time to come in as a teacher because at this point you could be just in the same mix as everybody else,” Peavy said.

AJ Hillis, a first-year teacher at Paul Duke STEM, completed a yearlong STEM residency in July and is working toward his teaching certification through the Teach Gwinnett program, with Peavy serving as one of his mentors.

“As we’ve gone through the year, I’ve noticed that the same struggles I’m having are the struggles that everyone else is having, and so it does feel like there’s kind of unity in the chaos,” Hillis said.

By the numbers

- 5,940 — Georgia new teacher full-time headcount*

- 113,900 — Georgia total teacher full-time headcount*

- $44,038.94 — Georgia new teacher average annual salary*

- 5,443 — candidates completing teacher preparation programs in Georgia in 2012-2013

- 3,807 — candidates completing teacher preparation programs in Georgia in 2017-2018 (most recent available data)

- 8% — average number of teachers who leave the profession each year

* As of fall 2019; fall 2020 data collection is ongoing

Sources: Southern Regional Education Board and Georgia Department of Education