Chris Perlera is the U.S.-born son of Salvadoran parents. But he is more than that. Perlera is both Hispanic and Republican — not an easy combination in the Year of the Donald.

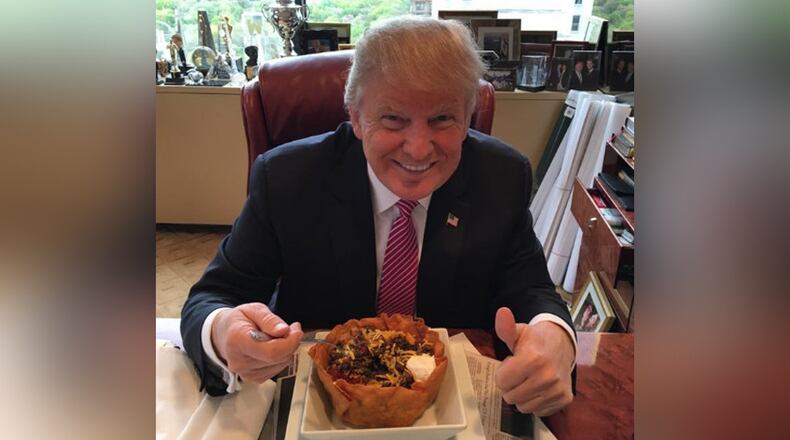

Talk of deporting millions upon millions of illegal immigrants by a presumptive presidential nominee worries him. Donald Trump’s use of a lunchtime “taco bowl,” last week’s symbol of his goodwill toward Hispanics, did nothing to change that.

Perlera refuses to vote for Hillary Clinton, who will likely become the Democratic nominee for president. But he says he won’t be able to bring himself to vote for Trump.

“He does not have my support. He represents some things that border on dictatorship,” said Perlera, 30. And yet the entrepreneur in Perlera sees a silver lining in the rise of a New York billionaire who would wall off Mexico and bar entry to Muslims of all nations.

Three months ago, Perlera started a one-man public affairs firm in Atlanta. This year’s market: Republican elected officials who are worried about the devastating effect that Trump could have on down-ballot races in Georgia and elsewhere in November.

“General election campaigns are going to need my help significantly, due to the Trump trickle-down effect of putting generally positive and well-liked Republicans at risk in districts where there’s a lot of diversity,” Perlera said.

The task ahead seems to shift day by day. “It’s really that contrast between Paul Ryan Republicanism and Trump Republicanism. Or what (Trump) calls Republicanism,” Perlera said. “It’s a difficult climate.”

That climate can be seen in the results of a multilayered Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll that looks at the November presidential contest and other issues.

More than one-quarter of Georgia Republicans polled have an unfavorable opinion of their own party — significant evidence of a post-presidential primary fracture that needs tending. (Only 8 percent of Georgia Democrats express similar disappointment with their party.)

But the meat of the GOP down-ballot problem created by Trump can be found in the still somewhat hypothetical contest between the billionaire and the former secretary of state. When “leaners” are included, Trump leads Clinton by 47 percent to 44 percent in Georgia, well within the poll’s margin of error of 4.26 percentage points. Partisan voters are in predictable corners. The margin is even closer among independents, with Trump leading Clinton 43 percent to 42 percent. For Republicans, those are numbers to worry about.

Perlera and other Hispanic voters aren’t the problem. Not exactly. There’s been talk of a significant increase in Hispanic voter registration in Georgia, in response to Trump’s candidacy, but no documentation yet supports that assertion.

For the Georgia GOP, the problem is Hispanic voters as members of a broader alliance of the disappointed and disillusioned — a soup of race, ethnicity and ideology.

In 2002, the year that Republicans truly came to power in Georgia, whites made up 76 percent of the voting population. African-Americans made up 23 percent. All other voters made up a less-than-influential 1.7 percent. By 2012, the last presidential election year, white voters had dropped to 61.4 percent of the electorate, and black voters had climbed to 30 percent. Hispanic, Asian and “other” voters had quintupled to 8.7 percent — still a small portion of the electorate, but no longer insignificant.

Even so, if the trend lines hold, white voters in Georgia will make up less than 60 percent of the November electorate. Demographic alliances are the future of Georgia politics. And in some places, the future is already here.

We won’t have a firm grasp on the strength of U.S. Sen. Johnny Isakson’s Democratic opposition until well after the May 24 primary. Among Republican members of the U.S. House, five have general election opposition, but congressional districts in Georgia are packed in such a way that makes Democratic upsets unlikely even in the most extreme conditions.

The state Legislature is where Republicans in Georgia are most vulnerable should an anti-Trump wave strike in November. In the state Senate, we have 13 general election contests. In the lower chamber, 20 Republicans will face Democrats in November.

With a more conventional nominee at the top of their ticket, Republicans might be drooling over two targeted House districts, both inside the Perimeter, now held by white Democrats. The District 80 seat, won by Taylor Bennett in a special election last year, went 56 percent for Mitt Romney in the 2012 presidential contest. District 81, now held by Scott Holcomb, went 47 percent for Romney.

An anti-Trump wave in Georgia could place both out of the reach of Republicans.

And there are seats Republicans could lose in an anti-Trump backlash, especially in places such as Gwinnett County.

State Rep. Buzz Brockway, R-Lawrenceville, a Marco Rubio supporter, still hasn’t decided whether he’ll support Trump. “That’s a strange position for me,” admits Brockway, who has a solid record as a big-tent Republican who has worked to support minority candidates in his party.

In 2012, Romney won 59 percent of the vote in House District 102. “It’s not overwhelming, but it’s certainly a district that Republicans should win,” Brockway said. Yet the latest census figures show his House district to be 19 percent African-American, 15 percent Hispanic and 12 percent Asian.

“It’s a pretty diverse district,” Brockway said. “We’ve got a Korean-language church and a Romanian Baptist church, all within half a mile of my house.”

The GOP incumbent agrees that, if his district’s immigrant class takes unified offense at Trump and makes Republicans down the ballot pay, he could be in trouble. Brockway especially worries about the racial and ethnic undertones in the Republican standard-bearer’s promise to make America great again.

“Of all the things that Trump says and does, this is what I struggle the most with — this idea that conservatism is only for white people,” Brockway said. “I reject that, and I’ve never wanted to be a part of that. That’s the biggest thing I wrestle with, I guess.”

In the din that November is likely to bring, getting that message to his constituents could require a heroic effort.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured