Sam Olens makes his peace with LGBT students of KSU

We have seen Sam Olens, the Cobb County commission chairman, Olens the Atlanta Regional Commission chairman, and Olens the very Republican attorney general.

Metro Atlanta is now a witness to what happens when a politician is freed from the litmus tests of a GOP primary. “I enjoy my new apolitical life,” Olens said Wednesday. “I enjoy, when someone wants me to endorse them, or wants me to attend a fundraiser, that I get to say that I appreciate the opportunity, but I’m not coming.”

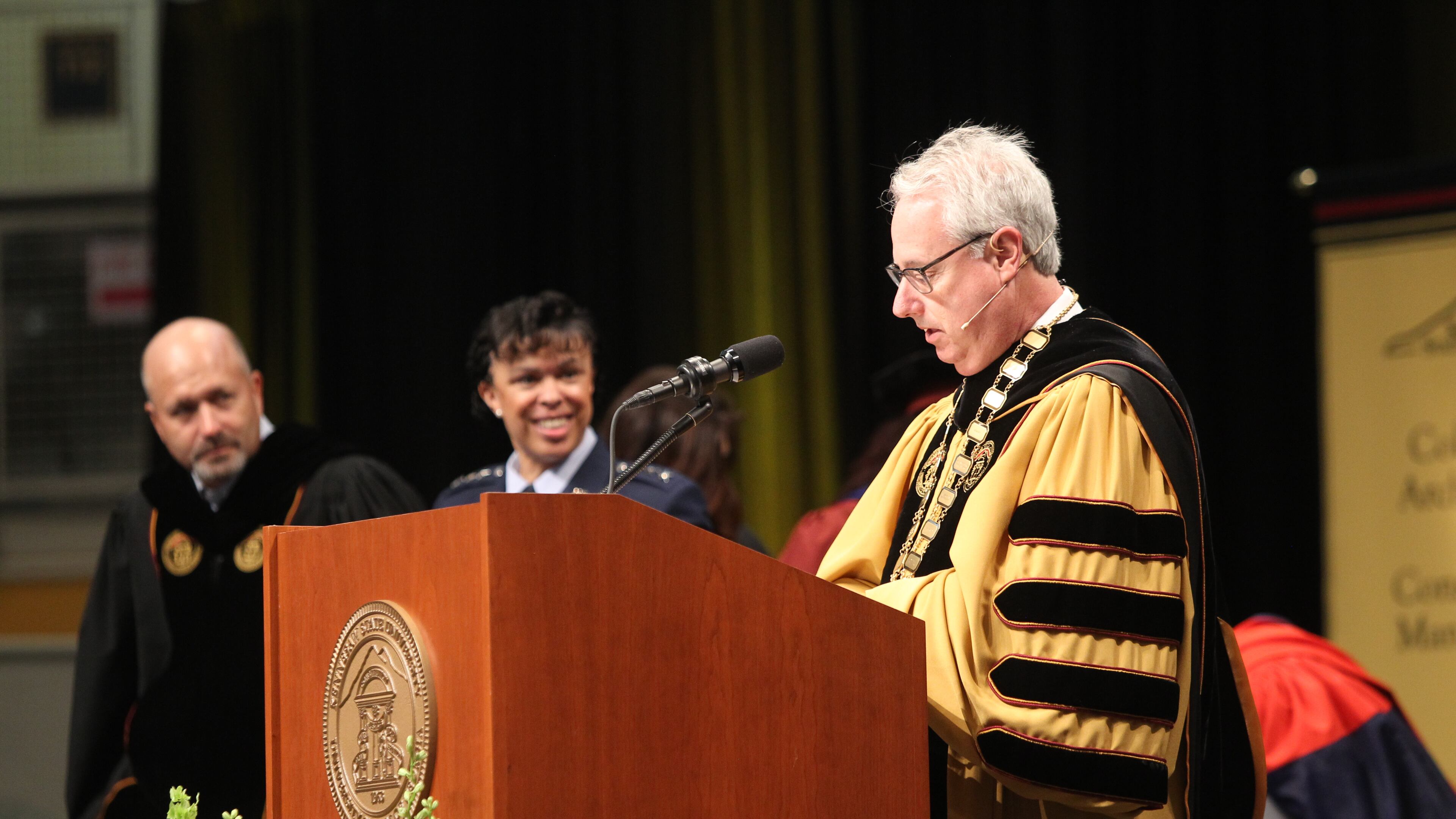

Olens was tieless and somewhat exhausted after the day’s five graduation ceremonies – the gowns are both heavy and hot. And he still had an evening women’s softball game to go.

On Nov. 1 of last year, Olens left his job as Georgia’s top litigator and took over as president of Kennesaw State University. On that first day, he had only to look out the window of his fifth floor office to see the mass of students and faculty on the green lawn below who loudly objected to his presence.

Some protested the fact that Olens had been the sole candidate for the job. Others were dismayed by his lack of the standard academic credentials. But most of the protesters focused on the fact that, on behalf of the state of Georgia, attorney general Olens, a Republican, had joined other states in federal legal challenges to gay marriage.

Most recently, Olens had joined legal objections to an Obama administration letter of “guidance” outlining the proper treatment of transgender students in public schools.

"Gay marriage bigot Sam Olens to become KSU president" was the headline posted by Project Q.

The new KSU president remembers the protest as large and serious, but brief. He accuses the media of blowing the confrontation out of proportion. I’m in no position to disagree. A week later, Donald Trump was on his way to the White House. My attention was elsewhere.

Still, in February, Patrick Saunders of the Georgia Voice, a newspaper geared toward the LGBT issues, published a piece alleging that in a short three months, Olens had made peace with many of those protesters. Let me quote two paragraphs:

Olens then instructed the school's chief information officer to get to work changing the school's Desire 2 Learn (D2L) class management system.

The system permits students to select the names by which professors and instructors call them. By fall, the Georgia Voice article said, students would also be able to select their preferred pronoun.

Now, that was something to talk about. I texted Olens, but had forgotten an all-important rule. Saunders had been lucky. Every year, from the second Monday in January until the end of March or beyond, the presidents of Georgia’s public universities collectively come down with a severe case of laryngitis.

They speak hardly a word, except through the state Board of Regents. This is the period when lawmakers in the state Capitol have their greatest control over what happens in Georgia’s institutions – via the budget.

With state lawmakers gone, we were at last able to meet at the end of KSU’s semester. “It’s been very smooth,” Olens said. Rather like returning to his days as the fellow who ran the Cobb County government. Except with a much bigger paycheck.

I asked him about his relationship with KSU’s LGBT community. “They are an under-represented population, a population that’s at risk, just as other minority populations are at risk,” the new president said. “And they want to feel safe. They want to feel protected. They want to have programs that are good for them.

“For some of the folks, my previously being an elected Republican was antithetical to them. I’ve sought to explain to them that not all Republicans and not all Democrats agree on the same hundred issues 100 percent of the time,” Olens said.

Many KSU students didn’t understand the role that Olens played two years ago, when nearly anyone who had ever cracked a law book understood that the U.S. Supreme Court was about to affirm the constitutional right of same-sex couples to marry.

Having seen the judicial revolt in Alabama that occurred when its state constitutional ban on gay marriage was overturned, Olens issued a warning to Georgia’s probate judges that whatever the U.S. Supreme Court said would be law in this state.

Gov. Nathan Deal backed him. (In retrospect, this was also a signal that Olens was no longer thinking about a run for governor in 2018.)

Obergefell v. Hodges came down that summer. “For five days after the decision, I was pretty busy telling probate judges to follow their oath of office,” Olens said.

He gave Jeff Graham, executive director of Georgia Equality, the state’s premier LGBT rights group, direct access to his staff – to report any judge in the state who refused to perform marriage ceremonies.

Graham gave Olens a timely, public vote of confidence when he was announced as KSU’s new president. “I do give him a lot of credit for a smooth transition in Georgia when the Obergefell decision came down,” Graham said this week.

On the same day the Supreme Court made its call, a member of KSU’s faculty went to the Cobb County courthouse and married her partner. “She asked me to have lunch with her and her spouse one day on campus, which I did,” Olens said. She expressed her thanks for what he had done as attorney general. He refused the credit.

“That was me following the law,” Olens said.

The KSU president is similarly by-the-book when I asked him about his university’s new system for allowing students to choose the names by which they are called.

“Now, are there going to be some transgender students that have a preferred name different from their given name? Yes. Just like my name is Samuel. Everyone calls me Sam. So we’re not making a special policy. It’s a consistent policy,” he said.

And the pronouns? “There was a suggestion," he said, but students will not be allowed to register their own pronouns.

Technology is one reason the topic won't be tackled, but logistics is another. Name changes need to be connected the right student transcripts. And there is the fact that students are students. A freshman may want to be called “Darth Vader Smith,” but wanting is not getting. "We have our handfuls doing preferred names," Olens said.

I asked Olens if he still considered himself a Republican. He said yes. But then that word came up again.

“Frankly, I love being apolitical. The people that follow politics I think, in many ways, are far more political than the folks on the ballot,” Olens said. “You know, as a county commissioner, there’s little you do that’s partisan. As attorney general, my job was to follow the law. It wasn’t to follow the laws that I liked, and not follow the laws I disliked.

“I’m most comfortable where I get to be me rather than carrying a platform,” he said.

Cathy Cox was once Georgia’s secretary of state. She lost a Democratic primary for governor in 2006 and is now dean of the Mercer Law School. She recently expressed a similar opinion, but was more blunt. “It’s a different breed of politics. It’s not as mean and nasty and you don’t have people paid to trash you,” Cox said.

I didn’t ask him, but there’s no doubt that Sam Olens would agree.