Out of the chaos of Iowa has come a hint of unrest among Georgia Democrats.

On Monday night, before the Midwestern meltdown, Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms was at an elementary school in Davenport, doing some caucus campaigning for former Vice President Joe Biden.

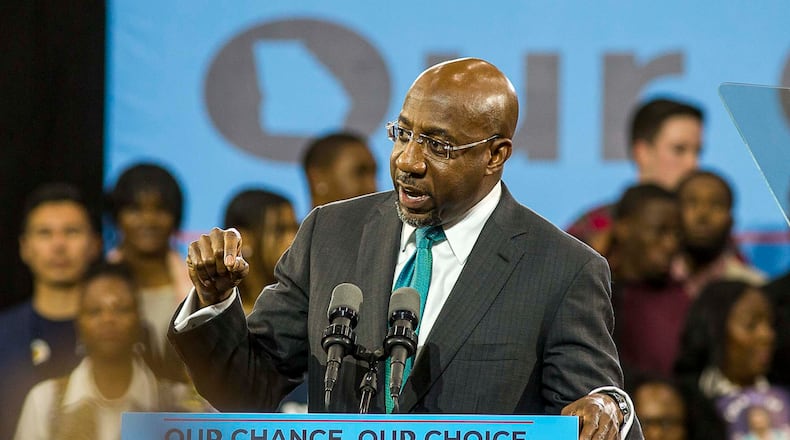

Only days earlier, lightning had struck in Georgia. The Rev. Raphael Warnock, pastor of the church once helmed by Martin Luther King Jr. and his father, had jumped into the U.S. Senate race against Republican incumbent Kelly Loeffler.

Within hours, Stacey Abrams, the former Democratic candidate for governor, endorsed Warnock. The next day, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee followed Abrams’ lead – despite the fact that the race already had one Democrat in the race, with more expected.

When my Journal-Constitution colleague Greg Bluestein caught up with Bottoms, he put forth the obvious question: Would Mayor Bottoms also be endorsing the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church?

Not anytime soon, she said. It might depend on what DeKalb County CEO Michael Thurmond does.

“I have a great deal of respect and regard for Reverend Warnock. I don’t know who else is getting in. CEO Thurmond has not ruled it out yet. It’s going to be a matter of waiting to see who’s in and who’s not — and making a decision at that time,” Bottoms said.

But the mayor of Atlanta went further than a coy “wait-and-see.” Bottoms said she wasn’t brought into the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee’s decision to give Warnock its early endorsement — a huge signal for other outside groups to open their wallets to Warnock as well.

“I didn’t expect to be, either,” the mayor added. The situation is made stickier by the fact that Warnock’s wife, Ouleye Ndoye, works in the Bottoms administration.

Ladies and gentlemen, that sound you just heard was the shifting of a tectonic plate in Georgia Democratic politics, another measure of the impact Abrams has had on her party since her near-miss in the 2018 race for governor.

For decades, Democratic political clout has been concentrated in the offices held by Democratic elected officials — who controlled networks of supporters and campaign contributors. When the state Capitol was lost in 2002, that influence shifted to local officials.

But since Maynard Jackson’s election in 1973, it would be hard to pick out a major political decision within Democratic circles that didn’t involve the mayor of Atlanta.

That influence has now devolved upon Abrams and her post-2018 network of voting rights and census-focused groups, financed with pools of cash that previous Georgia Democrats could only dream of accessing.

State Rep. Calvin Smyre, D-Columbus, has served in the Legislature since 1974. He became the first African-American chairman of the Democratic Party of Georgia more than 20 years ago.

“Usually, the process has been going to the various levers of the political process,” Smyre said Tuesday morning, after seeing the comments from Mayor Bottoms. “It’s a changing of the times and the political landscape.”

Bottoms’ remarks also gave me permission to hound Thurmond about his potential candidacy. He heads up the government of DeKalb County, which each November produces the largest cache of Democratic voters in the state.

Thurmond spoke of a lack of communication and routine diplomacy. “It did not occur. That’s the problem. The communication did not occur. Everyone respects Reverend Warnock. That’s not the issue,” Thurmond said. “It’s the lack of appropriate communication and inclusion that – at the end of the day – will improve the probability of success.”

And is he running? “I’m very happy where I am as CEO of DeKalb County. Many people have encouraged me to run, and I’ve not ruled it out.”

Part of the Warnock situation can be attributed to the declining influence of political parties – a nationwide phenomenon. (Georgia chairman Nikema Williams said she would not be endorsing in the Senate race.)

Then there is the fierce urgency that many Democrats feel has been created by the rise of Donald Trump and a GOP-controlled U.S. Senate that on Wednesday is all but certain to acquit the president of charges that he attempted to arm-twist a foreign country into interfering in the 2020 presidential campaign.

“In addition to acknowledging the reach that Stacey’s cultivated in the last couple years, and how close Democrats got in 2018, there’s a desire not to miss the train – to get aboard,” said Howard Franklin, a senior advisor to Michael Bloomberg’s presidential campaign in Georgia.

Franklin considers the Abrams-Warnock alliance a natural outgrowth of Abrams’ theory that the center of the political spectrum – the acreage between Republican and Democratic lines – no longer holds the key to political power in Georgia.

To that point, Matt Lieberman was the first Democrat to announce for the U.S. Senate seat given up by Republican Johnny Isakson. Lieberman said he met with DSCC staffers in Washington last summer. “We had, I would say, infrequent contacts after that,” said Lieberman, son of former U.S. Sen. Joe Lieberman of Connecticut.

Lieberman said that the last time he spoke with anyone with the DSCC, about three weeks ago, it was “pretty clear” that they would be backing Warnock.

Another Democratic candidate, former state senator and federal prosecutor Ed Tarver of Augusta, plans to officially announce his candidacy next week. Tarver, who like Thurmond is African-American, declined to comment on the endorsements that Warnock has gathered up.

Lieberman, Tarver and Thurmond have all been residents of the political middle. Former state attorney general Thurbert Baker, also African-American, would be another example. Warnock isn’t cut from that cloth.

The DSCC referred to Warnock as “a longtime advocate for health care and economic justice.”

The best line from Abrams’ endorsement of Warnock: “I prayed with him as we worried for our fellow Americans who have not benefited from an economy that demands more and more from them, but delivers less and less.”

But this abandonment of the middle isn’t just a Democratic thing. Republican supporters of U.S. Rep. Doug Collins have used an identical argument for the Gainesville congressman’s decision to enter the same contest. It is no coincidence that both are men of the pulpit. They know how to work up the enthusiasm of a congregation.

Oddly enough, the biggest current believer in Georgia’s political middle may be Gov. Brian Kemp, whose appointment of businesswoman Kelly Loeffler to the Isakson seat last month was intended – in part – as a November appeal to suburban, white female voters who find President Trump more than a little off-putting.

But with Collins in the race, Loeffler now doesn’t dare let a sliver of light get between her and the man in the White House. Her gender advantage is diminished, and the center may not hold.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured