As a matter of ceremony, Michael Thurmond will be sworn in as the new CEO of DeKalb County government on Friday afternoon.

By law, he has actually held the position since New Year’s Day. In fact, Thurmond has already endured a weather scare – just a little dusting last week – and his first board meeting with commissioners.

Friday’s event will allow him to lay out his priorities and expound on the logo that appears on his celebratory website with the phrase, “New Day for DeKalb.”

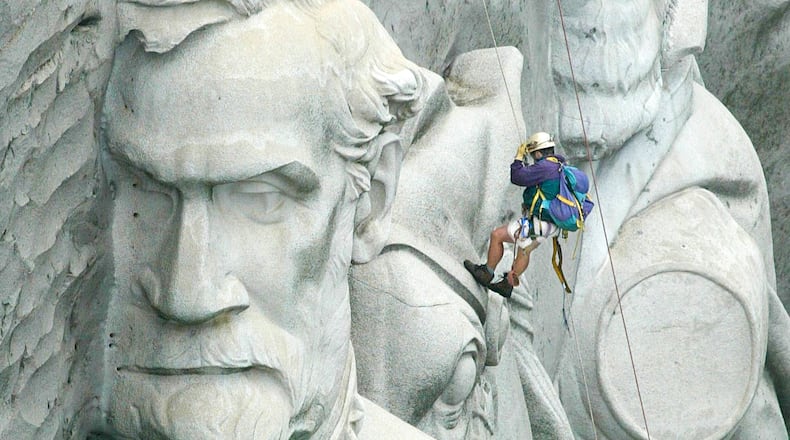

The image shows a sun rising behind a blue profile of the walkable side of Stone Mountain.

Thurmond, a former state labor commissioner and DeKalb school superintendent, was elected on a promise to unite northern and white DeKalb with southern and black DeKalb. For him, Stone Mountain is where that effort starts.

“I’m going to emphasize Stone Mountain as a major and significant attraction, a beautiful natural resource,” Thurmond said in an interview. “Not just a state property, but a county symbol as well.”

He would like to make the granite mound a rallying point for economic development in a county that currently struggles to generate jobs.

The problem: Stone Mountain may be the best-known geographic feature in all of Georgia, but because of its Confederate identity, it has become the most difficult state asset to successfully market.

The solution: “We have to create a narrative that extricates us from this conundrum of history that we’re in,” Thurmond said. The Lost Cause of the 19th century must be reconciled with what has followed.

We have been here before. Eighteen months ago, in the days after Dylan Roof massacred nine members of a black church in Charleston, S.C., the mountain and its massive carving became a focal point for debate over Confederate symbolism.

The result was a pair of efforts not to remove Confederate iconography, but to add to.

Bill Stephens, the CEO of the Stone Mountain Memorial Association, proposed the erection of a bell tower atop the mountain, to mark its mention in Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech in 1963.

When that idea stalled, the effort shifted to the creation of a museum that would detail the role African-Americans played in the Civil War — mostly as enslaved logistic support on the Southern side, and soldiers on federal side. That initiative, too, has so far come to naught.

Thurmond would revive the conversation. In addition to a long career in politics, the DeKalb CEO is also an amateur historian who believes that we are the stories that we tell ourselves. Incomplete or inaccurate history, he argues, leaves its mark on the generations that follow.

“We don’t connect current issues with what, unfortunately, is a very disturbing part of the history of our county. Which is Stone Mountain as the birthplace of the modern Klan,” Thurmond said.

That was in the early 20th century. But the thing about history is that it doesn’t tend to stop. Everyone knows the tale of how Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested in 1960 at a demonstration in Atlanta. “But he had a pending case in DeKalb for driving with an Alabama driver’s license. It was a DeKalb County judge who sentenced him to four months of hard labor [at Reidsville State Prison],” Thurmond said.

“So when Dr. King spoke about freedom ringing from Stone Mountain, he was speaking about it metaphorically, but he also had that experience,” he said. “In many ways it’s recent history. And we have to come to grips with that,” he said. “And in many ways, we have to make peace with it — before we can really embrace all the opportunities that now exist for DeKalb in the early part of the 21st century.”

Again, Thurmond is about adding history to the park, not obliterating it. “That carving is nothing to be ashamed of, but we need to put it in the proper context — the meaning and significance,” Thurmond said.

“I live in the shadow of Stone Mountain. I see it every day. So I speak in a more personal way than some people might. It’s a part of my every day existence.”

Curiously, our conversation happened on Tuesday, the same day that a federal jury in South Carolina sentenced Dylan Roof to death for those church murders. His name did not come up.

This isn’t about cultural retaliation. Thurmond is about piecing a broken DeKalb back together. And if he can successfully recast the Stone Mountain discussion in economic terms, he may be doing everyone a favor.

Details on how Thurmond intends to accomplish that will have to wait until Friday. He has a bully pulpit, but whatever he attempts, the new CEO will need Republican help — specifically, northern DeKalb help. And certainly some assistance from certain quarters in the state Capitol as well.

For instance: Perhaps the board of directors of the Stone Mountain Memorial Association shouldn’t be all white. Minorities have been appointed to it before. And an African-American member or two might offer some interesting perspectives on the stories we tell ourselves.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured