Answering machines were still something new on the scene in 1984. And this one, it could be said, changed the course of Georgia politics. And is still doing so.

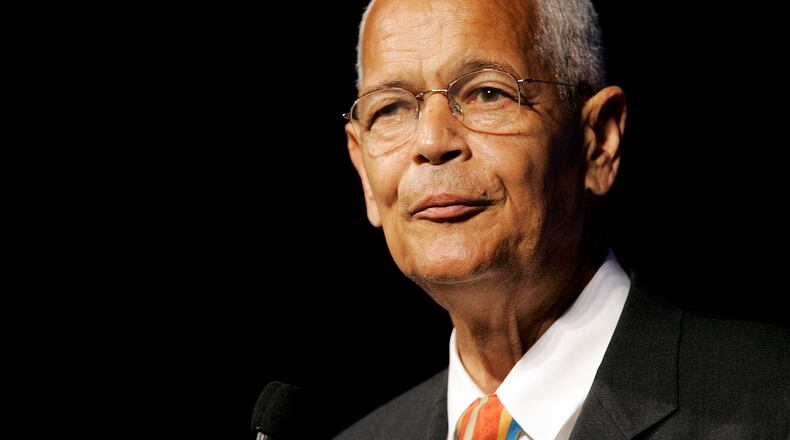

The electronic gizmo belonged to Julian Bond, then perhaps the most famous state senator in the nation. He was erudite. He was handsome. He had been nominated for vice president. He lectured. He traveled. He had hosted NBC’s “Saturday Night Live.”

And this is the message that he left for constitutents who called his Atlanta home:

"I'm sorry if there is no one here to answer your phone call, but that is the way it is . . . Please don't leave a message on this phone. It does not like them and will not take them."

A 28-year-old upstart by the name of Hildred Shumake challenged Bond in that year’s Democratic primary. He went door to door with a tape recorder, playing Bond’s high-handed phone message. Bond would beat back Shumake, but only with 54 percent of the vote. Not an impressive showing for a man who was a household name and was closing in on 20 years in the state Legislature.

As famous as he was, Bond was vulnerable.

In 1986, one of Georgia’s classic backroom deals was cut. If Democrats didn’t go after U.S. Sen. Mack Mattingly, who had ousted Democrat Herman Talmadge six years earlier and was seeking re-election, Republicans would lay off Gov. Joe Frank Harris, a Democrat who would also be on the November ballot.

U.S. Rep. Wyche Fowler, D-Atlanta, either didn’t know of the deal, or chose not to observe the terms. He announced his candidacy for the U.S. Senate, opening up his 5th District congressional seat.

Then as now in Georgia, opportunities for promotion within the African-American political community were rare. And two Civil Rights stalwarts, both young men during the hot days of the early ‘60s, had been stewing in the backwaters too long to do their careers any good.

Bond was the favorite. He had spent the last two years in the Legislature in anticipation of this moment, boosting the black voting population of the 5th District. Socially, he was part of Atlanta’s upper crust, the son of a university president who could take any opponent apart with his tongue, whether in a debate or a TV studio.

He was by far the favorite in black community, though there was quiet talk that he hadn’t quite fulfilled the promise he’d shown when he came on the local political scene in 1965. Bond had once called himself lazy, but more likely he was bored.

By contrast, John Lewis was the slow-talking son of an Alabama sharecropper, who often struggled with pronunciation. He was now an at-large member of the Atlanta City Council – a fact that would become important. Buckhead voters knew him.

Rick Allen, then the political columnist for the Atlanta Constitution, was at Lewis’ kick-off, when the nation’s poster child for nonviolence first showed an aggressive streak. These paragraphs would become prophetic:

In that one instant, the real stakes of the contest came into full view. The 5th District race is a last hurrah for two men who were, just a decade ago, giants on the American landscape, and who are now, day by day, diminishing in stature before our very eyes.

The winner, taking his place as the only black congressman from the Deep South, will regain national prominence overnight. The loser will fall deeper into the shadows, perhaps never to escape. There are other candidates in the field, but for now they are distinct underdogs, serving as spectators watching a high-noon, winner-take-all showdown.

In Lewis’ 1998 memoir, “Walking with the Wind,” he addressed the class distinctions:

And yet now he wanted to be a congressman. And everyone assumed he would be a shoo-in. And that bothered me a great deal. I had long resented the accepted tradition in the city of Atlanta of a select few leaders, black and white, handpicking and determining who went to Washington. I didn't like the idea of someone being anointed.

That goes back to the SNCC ethos, I guess – the belief that the masses should truly decide their fate and be able to choose their representatives rather than be controlled by a chosen few. The assumption that the job was Julian's if he simply wanted it just rubbed me the wrong way.

Bond nearly pulled it off, winning 47 percent in an August primary, to Lewis’ 35 percent. Again, in his 1998 memoir, Lewis described how Bond questioned his ethics during a debate leading up to the September runoff, pointing to a campaign donation:

I was stunned. I could not believe he was questioning my integrity, of all things. And he knew, he knew, this was not true. My immediate reaction was "I'm not going to let this Negro get away with this." I said that to myself.

My advisor Kevin Ross had told me over and over in preparing for these debates, "If they try to set you up in any way, don't back down. Go for it. Do whatever you think you should. Strike back."

It's not in my nature to let my emotions rise up. It's not in my nature to strike out. But this was a time when it happened. This was a time when I hit back.

"Mr. Bond," I said. "My friend. My brother. We were asked to take a drug test not long ago, and five of us went and took that test. Why don't we step out and go to the men's room and take another test?"

The room was dead silent. You could have cut the tension with a knife.

"It seems," I went on, "like you're the one doing the ducking."

Julian was flabbergasted. He gathered himself and responded with a nervous joke about "Star Wars" and "Jar Wars." But no one was laughing.

Bond labeled the drug challenge as "demagoguery" and "McCarthyism." From the New York Times article that documented the outcome:

With all 241 precincts reporting in the unofficial count tonight, Mr. Lewis had 34,548 votes, 52 percent of the total, to 32,170 votes for Mr. Bond.

After the outcome become apparent, Mr. Bond told his supporters: ''We appreciate what you've done. I want you to know that the day may come when we may ask you to do it again.''

That was not to be. The next year, Alice Bond, the wife of Julian Bond, went to the Atlanta Police Department’s narcotic squad, to complain that a woman with whom her husband was dallying had cocaine connections – and had slashed Mrs. Bond’s face with the stiletto heel of her shoe.

From one of many Journal-Constitution articles on the topic:

The 27-year-old plainclothes officer to whom she entrusted her secrets was not one known for his tolerance of politicians' faux pas. Surmising that his superiors cared not for any investigation that would jeopardize their pensions, Officer Richard Hyde quickly shared Mrs. Bond's revelations with the FBI.

The scandal eventually petered out, but Bond's electoral career was finished. He would spend the next 25 years remaking himself, eventually closing out a rich public career as head of the NAACP. Mostly away from Atlanta.

But what happened in 1984 still matters. John Lewis remains a venerated figure in Washington. And that Richard Hyde whom Alice Bond confided in? He’s the same Richard Hyde who is now working with former attorney general Michael Bowers on an investigation of DeKalb County government.

That was some answering machine.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured