One of the more important voices in the world of religious conservatism is leaving the field. At least for now.

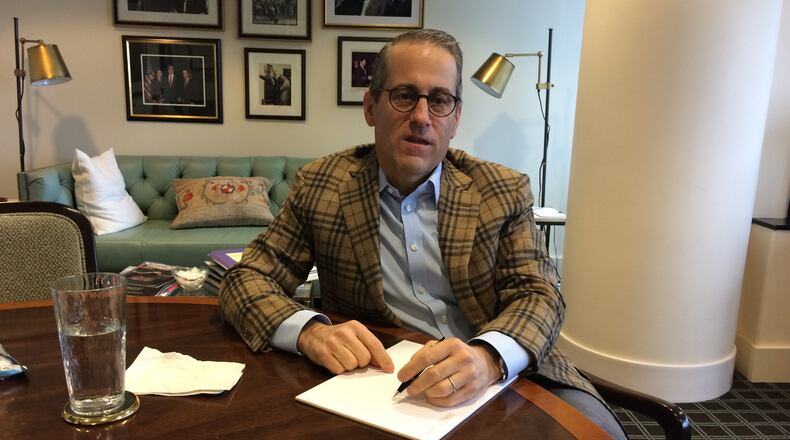

Last week, Mark DeMoss quietly announced that he would soon close his boutique public relations firm in Buckhead, which for 28 years has told the stories of dozens of A-list conservative Christian clients.

Donald Trump isn’t the reason he’s calling it quits.

But it’s fair to say that, for the last three years, DeMoss has exemplified one-half of the schism that has erupted within the evangelical community over a president whose personal language, conduct and history isn’t endorsed by anything in the New Testament.

“My wife says I’m done with politics. And I love her enough to listen to that. I have mixed feelings about politics. There’s a side of it I like, and increasingly, there’s more that I hate,” said DeMoss, a spare figure in a glass office. “I have a lot of concerns about where things are politically with the church and evangelicals.”

“You’re seeing a lot of what I would consider voices of reason being run out of the Congress and run out of government — and certainly run out of the Republican party,” DeMoss said.

DeMoss’ three-decade career has spanned the rise of religious conservative influence within the GOP. He has served as counselor to American evangelism’s two most famous father-son teams — the Falwells and the Grahams.

Straight out of Liberty University in 1984, DeMoss became chief of staff to the Rev. Jerry Falwell Sr., founder of the Moral Majority, which had already helped push Ronald Reagan into the White House.

You have seen DeMoss at work, though you may not know it. In 2017, when the Museum of the Bible opened in Washington D.C., DeMoss was in charge of the details. When the Rev. Billy Graham died last year, the official announcement came through DeMoss’ office on Peachtree Road. The Atlanta publicist has continued to work with Franklin Graham.

More significantly, when Mitt Romney sought the GOP nomination for president — in vain in 2008 but successfully in 2012, DeMoss served as his liaison to an evangelical community suspicious of the candidate’s Mormon faith. DeMoss urged his colleagues to look past Romney’s religion and judge him by his values.

But in 2016, Trump became a bridge too far. DeMoss held a prominent post on the governing board of his alma mater, Liberty University, whose president was Jerry Falwell Jr.

The university president gave a full-throated endorsement of Trump during the GOP presidential primary. In an interview with the Washington Post, DeMoss expressed criticism of the front-running Trump, saying the candidate was a rejection of all that Liberty University stood for.

In the end, DeMoss resigned from the board.

DeMoss has tilted at a few windmills in his life. In 2009, concerned with the declining state of the nation’s political dialogue, he embarked on a short-lived “civility” campaign. His Democratic partner was Lanny Davis, a Hillary Clinton supporter. Davis is currently part of the legal team representing Michael Cohen, Trump’s former personal attorney – who is now giving evidence against his old boss.

Yet as a traditional Baptist, DeMoss takes our constitutional ban on religious tests for public office quite seriously. On an office wall in his 20-person firm hangs a copy of a full-page ad that ran in the New York Times a few years ago. The headline: “Burning the Qur’an does not illuminate the Bible.”

But to DeMoss, it is Romney and Trump — the latter is nominally a member of a traditional Christian denomination — who best illuminate the current split within the evangelical world.

“What we evangelicals preached for the last 40 years really got tested with a Mitt Romney nomination. Do we, in fact, believe that family values and character and integrity matter most? And do they matter more than a candidate who shares your faith or theology?” DeMoss asked. “I’m more interested in a candidate that shares my values.”

Suffice it to say that DeMoss was present in Washington this month when Romney was sworn in as the newest U.S. senator from Utah.

DeMoss would like you to know that he isn’t closing his shop out of weakness. His public qualms about Trump haven’t hurt his firm, which had a solid 2018. Nor is his health an issue.

A 2017 bout with cancer is in remission, but the fight did require him to focus on the basics. "I love the practice of PR. I don't even like the business of PR. I love giving advice, navigating a crisis, solving a problem, shaping a message. I don't love ownership and chasing a client," he said.

DeMoss is quite blunt about what he’ll do next. “The short, immediate answer is that I honestly don’t know,” he said.

But he is concerned about where his world and his friends are headed. I asked DeMoss to describe the arc of the movement he helped propel.

From the early ‘80s, he said, he watched Falwell Sr. transform from a preacher who counseled against involvement in politics into a leader who encouraged Christians to dive in. “Then I watched him and countless other religious conservatives preach that our loyalties should be not to a party, but to values,” DeMoss said.

Think Bill Clinton.

“Now what I think what we’re seeing, in a big way, is an increasing loyalty to a party — even if it means dispensing with certain values,” DeMoss said.

“Pragmatism” was the polite description that he gave the willingness among some evangelicals to trade U.S. Supreme Court appointments for a set of blinders.

“I think there have been a lot of trade-offs that we will look back on some day and say, ‘That was too high a price,’” DeMoss said.

In the meantime, DeMoss said, it’s important to know that polarized politics in America doesn’t just mean Democrat vs. Republican, or liberal vs. conservative.

No matter what the polls say, evangelicals are divided, too. “I have pastor friends that had long, close relationships that have been really hurt and damaged,” he said.

But DeMoss believes in the political cycle and the pendulum swings of civic forces. There is still time for the situation to right itself.

DeMoss will close his firm’s doors in March. Perhaps by September, he’ll know what comes next. The betting here is that we’ll see him again.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured