Broadband in rural Georgia poised to become a 2018 election issue

In an election year, it is the fortunate politician who can stand, arms akimbo, between a voter and an unrelenting foe.

In much of rural Georgia, and in some urban deserts, that enemy isn’t Kim Jong-un or terrorists from the Middle East or an army of white supremacists.

It is the local Internet provider.

In a recent interview, House Speaker David Ralston, R-Blue Ridge, named improved Internet access in rural Georgia as a priority for his chamber in 2018.

State Sen. Steve Gooch, R-Dahlonega, would have you know that he filed a bill on the same topic months before that. The mystery of the missing megabytes has also become an essential paragraph in stump speeches for statewide candidates across the political spectrum.

And U.S. Rep. Doug Collins, R-Gainesville, says to one and all: Welcome to the party. “I’m excited to actually see the state, especially statewide candidates and others, recognizing that broadband’s a problem in rural America,” Collins said this week. “That’s actually encouraging to see. We’ve been on this for five years.”

Collins is spending much of the August recess talking about his bill to increase competition among those accepting government cash as part of federal program to increase broadband access in overlooked communities.

The congressman has become the ultimate consumer advocate in his Ninth District, where Windstream — an outfit based in Little Rock, Ark. — is the main Internet provider.

Collins tells of the sheriff who lost his Internet service for three weeks. Of the EMS unit in White County that was cut off for a day.

“I have pharmacists,” he said. “They can’t process credit cards, they can’t access records. This has become an economic development issue.

“Companies have got to stop coming into rural areas, buying telephone companies and Internet companies, thinking they can use the federal funds to basically offset their bottom line and not provide the services,” Collins said.

Last year, local news outlets reported on a meeting between Collins and Windstream CEO Tony Thomas in breathless terms usually reserved for U.S.-Russia summit meetings.

“We have people now who actually call our office before they call Windstream. This is that big of a problem,” Collins said.

And the resentment is not unlike the kind stirred ‘way back when a Ma Bell monopoly said you could have any color telephone you wanted, as long as it was black.

Collins' bill, one of several in Congress aimed at rural Americans, would defer capital gains taxes on Internet investments in state-designated "gigabyte opportunity zones," to encourage more companies to crack the rural Internet nut.

But the Gainesville congressman would also like to see an end to the “monopoly” established by the Connect America Fund, a program operated under the auspices of the Federal Communications Commission.

Windstream is drawing those CAF funds now. But as long as it’s doing so, no competitors can do the same — if those funds are used in the same territory. The program discourages competition, Collins maintains.

We called Windstream after talking with Collins, and were connected with Jarrod Berkshire, president of Windstream’s Georgia operations.

The CAF program, Berkshire said, “wasn’t designed to reach every customer, and it never will. Rural broadband is not a switch you can flip and have it come on.” He counsels patience.

Windstream has a broadband signal within reach of 740,000 households and businesses, but for every federal dollar it takes, the company’s investors spend ten, he said.

Steve Gooch, the state senator from Dahlonega, also represents an area dominated by Windstream. Poor Internet service is the top complaint he hears from constituents, he said.

Gooch's Senate Bill 232 would make it easier, and cheaper, for Internet providers to obtain access to public rights-of-way for their fiber. It would also specifically authorize electric membership corporations to get into the Internet business – another effort to increase competition.

Like Collins, Gooch thinks that expanded broadband access is a foundational cure for much of what ails rural Georgia, from health care to a lack of jobs to classrooms hampered by a lack of access to both teachers and information.

An opioid treatment center is scheduled to open in Dahlonega on Sept. 10. It needs Internet speeds of 100 megabits per second. “In rural Georgia, you’re lucky to get 10 megabits — that are dependable,” Gooch said.

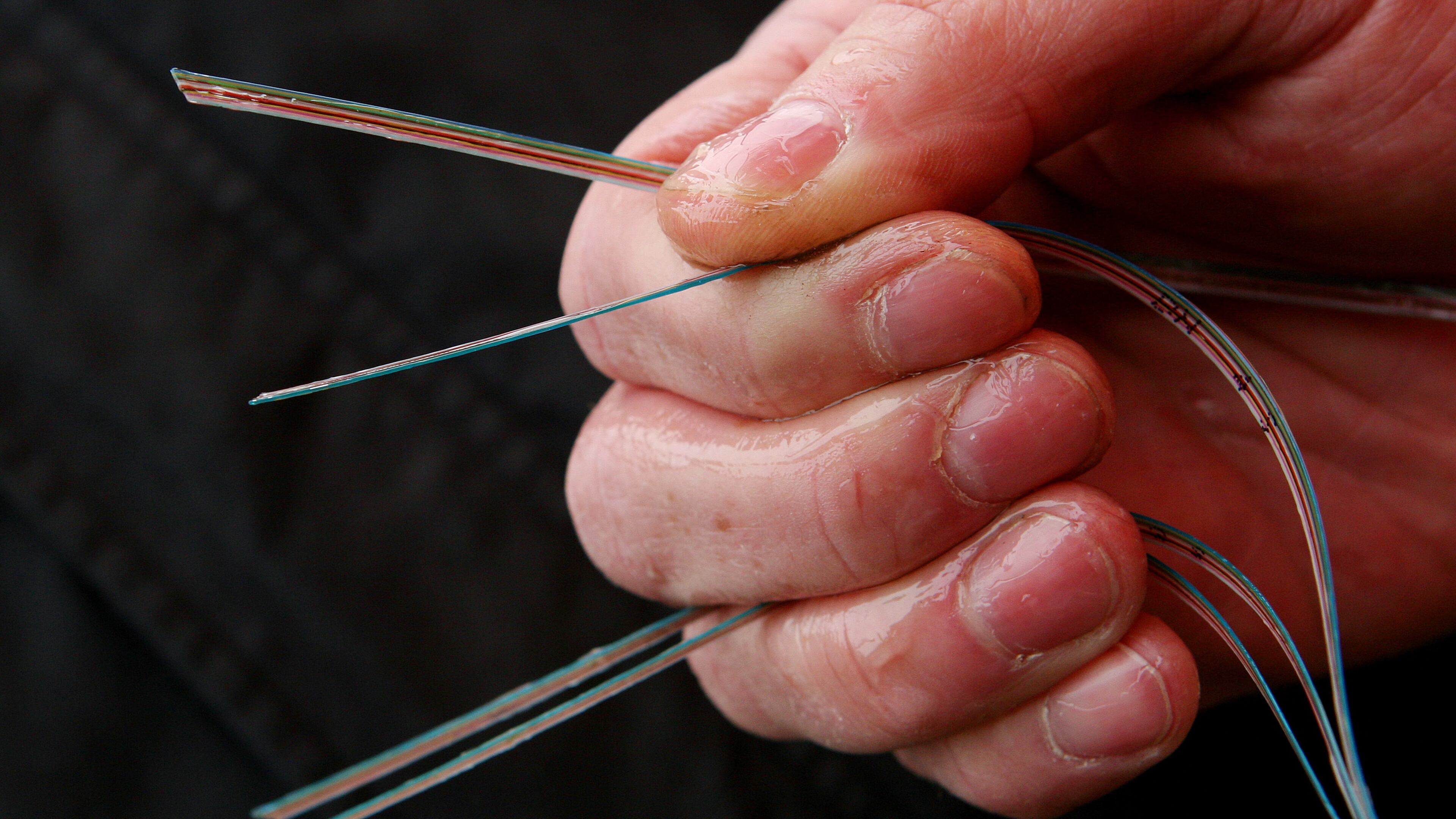

He’s looking for a grant that can be used to fund the necessary fiber optic lines to the treatment center. ”But the problem is that you can’t do that every day for every business,” Gooch said.

One of the more interesting moves related by Gooch could happen outside his legislation. The Dahlonega senator said the state Department of Transportation is exploring the idea of running mass-capacity fiber optic cables along Georgia’s interstate system.

Part of the capacity would be reserved for the DOT, perhaps to help guide autonomous vehicles of the future. But the private operator of the cable system would also serve as a kind of broker to Internet providers in many of the state’s more distant corners.

At bottom, what we’re talking about is a redefining of what we mean when we say “infrastructure.”

“In many areas, we don’t need a road. We may need a bridge fixed, but we don’t need a road. We need the infrastructure of the Internet,” said Collins, the congressman. “We’re not saying a guy who lives on top of a mountain 40 miles away is going to have 100 gigabit speed. But we’ve got to ask, what can we do for the vast majority of people who are being left out of this?”