There’s a clinical term for it – cognitive dissonance. It’s when you hold conflicting beliefs and know they’re in conflict. For example:

I like watching people play football.

I know playing football can be injurious to those people’s health.

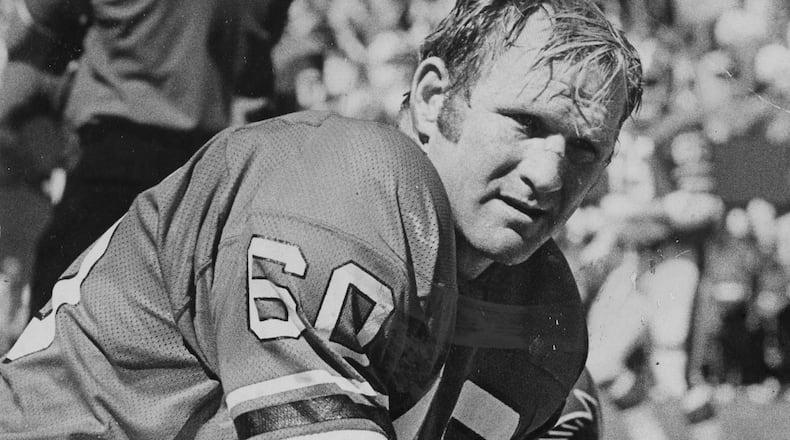

Steve Hummer's AJC story about the late Tommy Nobis has stirred my chronic C.D. Here was one of the toughest guys who ever played – All-American at Texas, No. 1 pick in the 1966 NFL draft, the best player on a decade's worth of lousy Falcons teams. Nobis died at 74 in December 2017 an angry and addled man. (Which, if you'd met him earlier in his life, you'd never have imagined.) His family, Hummer writes, tried to place him in an assisted-living facility. He was too abusive to stay.

Late last year, the Nobis family received a pathology report from the Boston group that tracks football-related damage. It revealed that he had Stage 4 Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, essentially a worst-case scenario. Such pathology involves slicing into the brain and therefore can only be done postmortem. The Nobis clan figured that was what had happened, but there was no proof until after the fact. Had there been, it would have done little good. There’s no cure for CTE.

We’ve read an ever-lengthening list of former footballers’ obits, and with many there comes an aftershock. Only in hindsight do we get some notion of what that famous athlete’s later life had become. We think of Junior Seau, dead of suicide at 43, or Mike Webster, dead of a heart attack at 50, having lived out of his pickup truck for a time. We think of Ken Stabler, diagnosed after death with Stage 3 CTE. We think of the elegant Frank Gifford, whose family revealed that he’d suffered from CTE.

These were not middling players. All four are enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. (That Nobis is not remains an unfunny joke.) CTE, we’re learning, doesn’t discriminate. It touches linemen and so-called skill players, passers and runners, stars and scrubs. Yes, these men chose to make their living in a rough sport, but if they knew then what we’re coming to know now, would they have made the same choice?

The NFL, as the NFL often does, feigned ignorance until the issue became too blatant to ignore. To its credit, it has tried to clean up the game for its current practitioners – aggrieved former players must file lawsuits seeking compensation – but how clean can a game be when the object of playing defense is to hit the other guy hard enough to knock him down and maybe dislodge the ball?

In November, Tim Green – a former Falcons linebacker who became a lawyer and an author – told “60 Minutes” that he’d been diagnosed with ALS, known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Green is 55. Dwight Clark, famed for his catch of Joe Montana’s pass against Dallas in the NFC title game, died of ALS last summer. He was 61. Steve Gleason, the revered Saint who blocked the Falcons’ punt in the Katrina Game of 2006, suffers from ALS. He’s 41.

Does football cause ALS? Green believes it caused his. He said he used his head – to tackle, not to think – on every play. He also said he stopped counting his concussions once he got past 10. He told NPR: "The temporary pain and discomfort, I knew that was worth it. Some pain in the future with my back, neck, knees, I knew that was worth it. Can I say getting ALS was worth it? I don't know. I don't know."

The latest NFL tempest has been the absence of a pass-interference call against the Rams’ Nickell Robey-Coleman in the NFC Championship game. Also unflagged on that same play was his helmet-to-helmet strike on Tommylee Lewis. Five days after the Rams prevailed in overtime, the league fined Robey-Coleman $26,739 for the blow. Even if refs are supposed to be looking for it, sometimes they miss it. And even if they see it and call it, a concussion cannot be undone.

As ham-handed as the NFL is in most everything it touches, it cannot remove violence from its product – or its product wouldn’t be football. And we Americans do like our football. There’s a reason the Super Bowl is the most-viewed television entity of every blessed year. There’s a reason this city is beside itself because two teams are going to play a game here Sunday night, which brings us back to cognitive dissonance.

With all we now know about the price some footballers wind up paying to make their livelihoods, can we still watch with an uncritical eye? If so, does that make us enablers? I’d love to tell you I’ve thought this through in a way that offers resolution – or, failing that, absolution – but I haven’t. I can’t.

I like watching football. Heaven help those who play it. Heaven help me, too.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured