The grind of SEC Media Days – 14 coaches and 42 players spaced over four days talking about a season that’s more than a month away, plus Steve Shaw’s periodic appearances to explain targeting – can dull the most heightened senses. But there came a moment this week when three men, the youngest of whom was 57, shared the podium and reminded us why we were there.

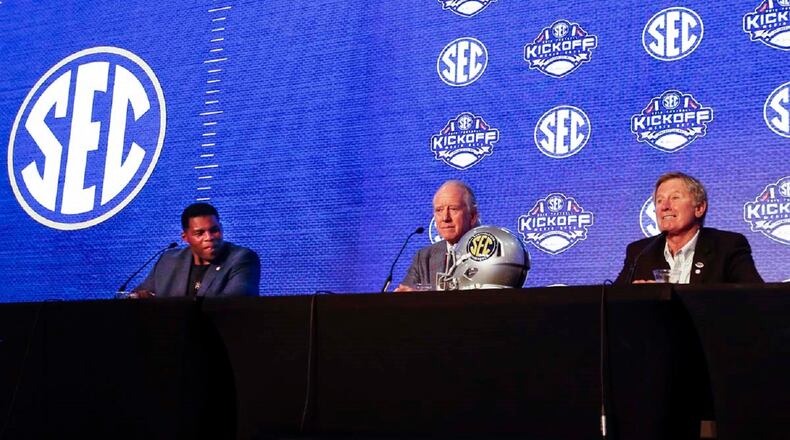

The three men: Archie Manning, one of the finest quarterbacks and the most noted sire in SEC annals; Herschel Walker, the greatest collegiate player ever; and Steve Spurrier, Heisman winner and coaching colossus and longtime fan of this correspondent. They assembled to discuss the 150th anniversary of college football, which this season will mark, but mostly they were there to let us gaze at them.

Every sport has history. Every sport has moments that endure. But there’s something about college football, especially college football in the South, that calls back the past as often as it looks to the coming schedule. For as much as we discuss who’s going to win the Georgia-Florida game in November, there are also those times when we sit back and say, “Remember the time Archie lit up Alabama?”

Archie, who’s 70, does. It was Oct. 4, 1969. That season marked college football’s centennial. Ole Miss, Archie’s team, wore a “100” decal on its helmets. The Rebels and Manning had been the preseason choice to win the SEC but had, unaccountably, lost at Kentucky 10-9.

Personal note: That was the first college game I attended. I was 14. Manning ran 67 yards for a touchdown, but the Rebels – who would later concede that Johnny Vaught was saving his best plays for Bear Bryant the next week – fumbled on the goal line at game’s end. Linebacker Wilbur Hackett, the SEC’s first African-American team captain, recovered. UK won 10-9. It was amazing.

The Ole Miss-Bama game at Legion Field was the first prime-time network telecast of a regular-season college football game. It started at 9:30 p.m. Eastern time because, as ESPN's Ivan Maisel has written, Lawrence Welk refused Roone Arledge's request to bump up his show. Those who stayed awake – I didn't; my dad did – watched Manning pass for 436 yards and run for 104 against Ken Donahue's famous defense. Ole Miss lost 33-32. The Crimson Tide's Scott Hunter passed for 300 yards. Seven SEC records, none involving defense, fell. According to Maisel, Bryant told Vaught it was the worst game he'd ever seen.

Said Archie: “I’ve been to Birmingham a lot through the years – a lot of golf tournaments, a lot of friends – and everybody I see says, ‘I was there, I was there.’ The best I can remember, Legion Field didn’t have but 60,000 seats, and I’ve had 500,000 people tell me they were there that night.”

A night. A game. A historic performance. That’s college football. And isn’t it odd that, as much as we think of this sport as being staged on sun-dappled autumn Saturdays, so many epic moments happened after sundown? Archie vs. Hunter in Birmingham. Billy Cannon’s punt return in Death Valley on Halloween. Tommy Hodson and the Earthquake. Devin Aromashodu’s catch/run/fumble. The kid from Wrightsville trampling Bill Bates.

Speaking of that kid: Herschel retold the story of how he’d picked Georgia over, in order, the U.S. Marines, Clemson and USC in a series of coin flips. That’s an accepted part of Herschel lore. (Although when I was working for the Lexington Herald-Leader, I interviewed Herschel several times, and my recollection was that he wanted to be an FBI agent, not a Marine.) Beyond that, there’s nothing new to say about him, except this: Not many three-man panels could involve Archie Manning and Steve Spurrier and have them be no better than the second- and third-best players on the dais.

As for Spurrier, he began in grand style, reminding us that he just won another championship – in the Alliance of American Football, that pro league that shut down after seven games. His Orlando Apollos were in first place when hostilities ceased. Mike Bianchi of the Orlando Sentinel said his radio show has commissioned a trophy to commemorate this august achievement, and Spurrier, you’ll be shocked to hear, has agreed to come receive it.

But Spurrier, as often happens, cut to the heart of the hold college football has on its true believers. (He didn’t become the Evil Genius by being stupid.) Asked about rivalries, he noted that, unlike Yankees-Red Sox or Duke-North Carolina hoops, football teams meet, for the most part, only once a year. That ratchets up everything, and the result must be lived with for the next year. “When you win that game, your fans think they’re smarter and better than the other side,” he said. “And if you lose, you know the other side is thinking the same thing about you.”

One hundred fifty years after Princeton played Rutgers before a crowd estimated at 100 in New Brunswick, N.J., college football is a billion-dollar industry with stadiums that accommodate 100 times that many folks. We watch to see what will happen next, but much of the reason we watch is because we’ve seen so much already.

We know about the Four Horsemen and the Galloping Ghost. We hold vivid memories of Herschel and Bo and the many Mannings. We’ve been here many times before, and still we live for that moment when, yet again, toe meets leather.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured