House GOP tries new approach to beating back poverty

America’s longest war — 52 years and counting — has long been gauged by the munitions deployed rather than the ground gained. Consequently, the enemy in this conflict, poverty, has hardly retreated: Since Washington launched the offensive in 1964, the official poverty rate has hovered between 11 percent in good times and a touch over 15 percent in bad. Never higher, but never lower, either.

Some $22 trillion has been spent on scores of programs. Those figures are considered badges of honor by “hawks” who think the fight itself represents compassion. The “doves,” skeptical the fight is being fought well, tend to point to these same statistics, combined with the stubborn persistence of poverty in this country, as failure. And, importantly, as evidence the effort should be scaled back so it’s less costly.

Breaking a stalemate requires a new approach, and House Republicans have spent the spring re-imagining strategies in six key policy areas. First to report was a task force on poverty, and the most striking change ordered was this: It's no longer about cutting spending. The new anti-poverty plan is designed to be budget-neutral.

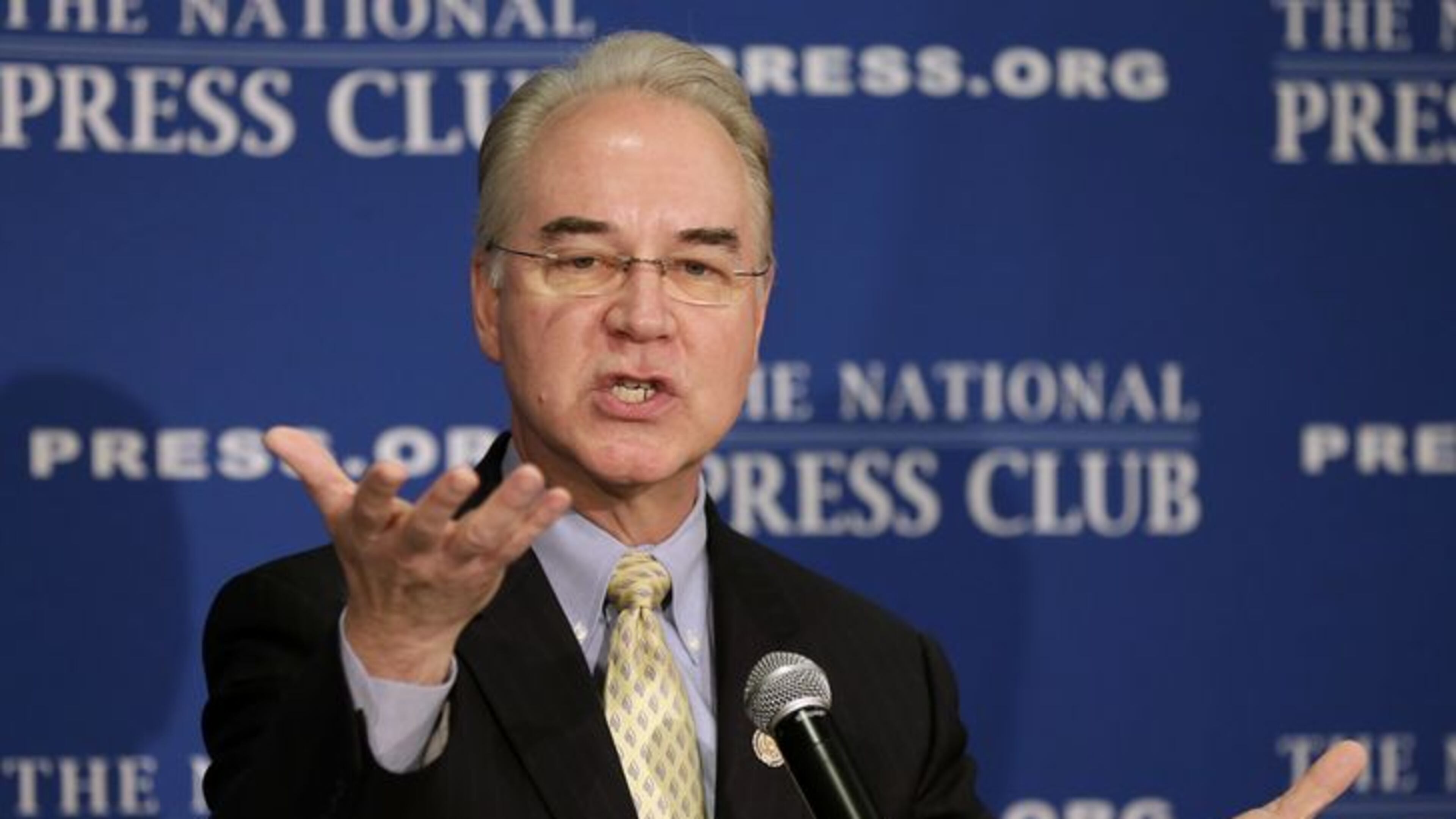

"It may be a rhetorical shift," one of the task force's members, Rep. Tom Price of Roswell, said in a phone interview this week, "but it certainly is a shift in focus from our perspective, and that is we've simply got to change the metrics that we use to measure success from a federal government standpoint: real people, real lives, real success in people's lives, instead of simply how much money we're throwing at the problem and how many programs we have."

The House Budget Committee chairman then drilled down more specifically into what ought to be measured:

“How many folks are we assisting in getting off governmental assistance?” Price began. “How many folks are we able to move them from a position of having no skills or a lack of education to having marketable skills and having an education? How many folks simply need a targeted assistance in the area of either nourishment for themselves or their family, or transportation to an endeavor or activity?

“Taking specific individuals and asking what is it that allows you to live your dreams,” he continued, “have to be the metrics. The metrics are defined by what people need, as opposed to what government measures easily – which is how much money are we spending, and how many programs do we have.”

The task force broadly outlined ways the federal government ought to move in that direction. One clear aim is to emphasize the importance of work and leading those on federal assistance toward self-sufficiency, requiring a job or job training for more welfare recipients. And the reason is not to save money in the short term — although that ought to come later — but to encourage what Price called “the earned success of employment and a satisfying life.”

“There are so many, as you know, great by-products just from a self-respect standpoint that flow from being a part of something greater than oneself,” he said. “And for many of us, that is the work endeavor that we select. So we ought to be encouraging and rewarding and incentivizing that activity, and the by-products of that are important in incalculable ways.”