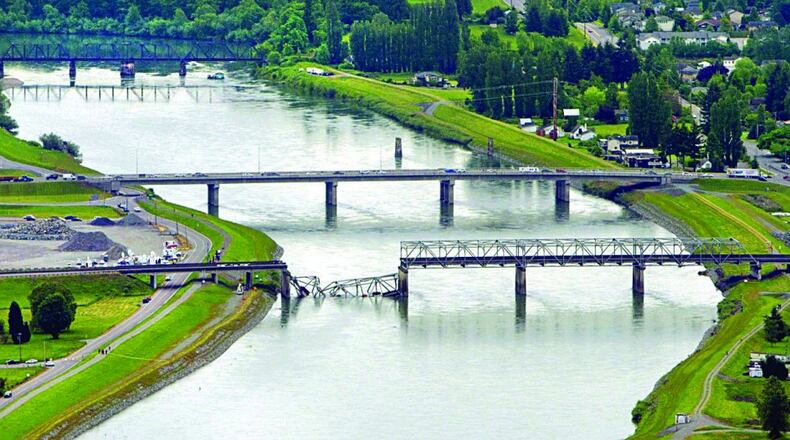

We may still be the United States, but we are not a united people. Our divisions have deepened, and the bridges across them have grown rickety, unable to bear much weight because we have invested so little in maintaining them.

You can see those divisions — divisions of race, class, education, generation and gender — with startling clarity in the political polls. In the most recent ABC News poll, Hillary Clinton boasts a 33-point lead among college-educated women, a 54-point lead among minority voters. Conversely, Donald Trump has a 19-point lead among white voters without a degree, and a 31-point lead among white men without a degree. And while young Americans vote overwhelmingly for Clinton; their grandparents vote strongly for Trump.

More importantly, you hear those divisions in our harsh rhetoric, and it’s not just coming from the politicians. I cast my first presidential vote 40 years ago, for Gerald Ford, and for most Americans, no election in that time frame has caused as much friction at the personal level as this one. We are losing a basic respect for the other side as well-meaning if perhaps mistaken fellow Americans, and without that respect, longstanding friendships and family relationships are hard to sustain. So too is democracy.

Our natural inclination, of course, is to blame our leaders for failing to lead, for failing to unite us. Why can’t they fix this? But our leaders are not the problem. The system isn’t the problem either. We, the people, are the problem.

We have replaced skepticism and self-doubt — the capacity to suspect that maybe, just maybe, the other guy could be right about a few things — with a fiery self-righteousness that is born not of confidence but of fear and defensiveness. It takes a certain degree of courage to keep open the possibility of error, to honestly test our beliefs against the facts. The easier course is to seek out affirmation not information, confirmation not truth.

And with so many seeking such affirmation, a profitable industry has arisen to fulfill that desire, to tell people what they want to hear. The usual metaphor is that of an information bubble, derived from "The Boy in the Bubble," the true story of a little boy back in the '70s who had no immune system and was forced to live in a plastic bubble, cut off from human contact. Bubbles now exist on both sides of the political spectrum, if to varying degrees.

Personally, though, I still prefer the hothouse metaphor. In a hothouse or greenhouse, you can grow beautiful, fragile flowers that thrive only in that highly controlled environment, in the exact soil, temperature and humidity range needed to grow them. However, if you open the hothouse doors and expose those plants to the cold winds of reality, they will wither and die.

That’s what happens in an election. That safe, comfortable hothouse environment of cyberspace and 24-hour cable news is forced open to reality, and all the things that you would like to believe are exposed to people whom you never see or meet or talk to, but who still exist and are every bit as real as you are. They get to vote on whether your version of reality matches their reality, and the price of membership demanded by democracy, the thing that demands united acceptance, is that we all accept that verdict, even if we would prefer a reality that was different.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured