Daddy Bush drops some truth

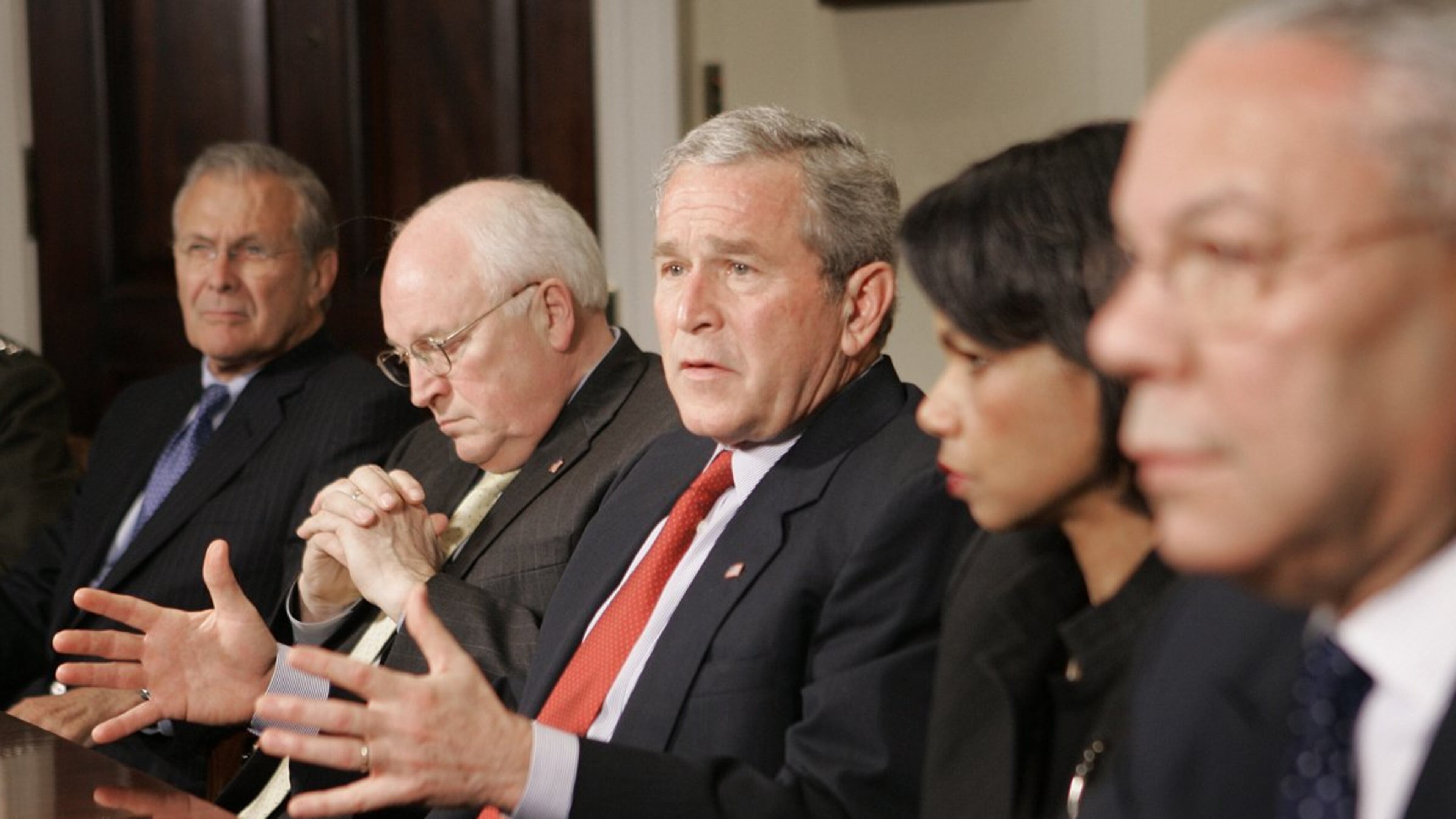

In a new biography of President George H.W. Bush, the patriarch of the Bush family is harshly critical of Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, central characters in his son's failed administration.

Rumsfeld, as defense secretary, was arrogant and "served the president badly," the elder Bush says. And Cheney, as vice president, was allowed far too much power and independence, using it to push the younger Bush into an overly aggressive response to the attacks of Sept. 11.

“(Cheney) had his own empire there and marched to his own drummer,” Bush 41 says, noting "his seeming knuckling under to the real hard-charging guys who want to fight about everything, use force to get our way in the Middle East.”

“The big mistake that was made was letting Cheney bring in kind of his own State Department,” Bush told his biographer. “I think they overdid that. But it’s not Cheney’s fault. It’s the president’s fault... The buck stops there.” ¹

I have long thought that would be history's verdict as well. Cheney, you may recall, was originally named by Bush to head the process of finding him a running mate, a process that magically resulted in the selection of Cheney himself. From the beginning, it seems, the self-assured Cheney recognized the younger, callow and uncertain Bush as someone he could manipulate. So when the attacks of Sept. 11 came, it was Cheney, not Bush, who seized control, to the point of telling Bush not to come back to Washington. And it was Cheney's paranoia and aggressiveness that drove the administration toward Baghdad.

Again, that in no way absolves Bush 43 of responsibility for the decision to invade Iraq -- the worst foreign-policy decision in American history -- and all that has since flowed from it. Asked to respond to the new book -- “Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush,” by Jon Meacham -- the younger Bush acknowledges that.

His father, the younger Bush now says, “would never say to me: ‘Hey, you need to rein in Cheney. He’s ruining your administration.’ It would be out of character for him to do that. And in any event, I disagree with his characterization of what was going on. I made the decisions. This was my philosophy.”

Tellingly, though, by the start of his second term, with events in Iraq growing more ominous by the day, the younger Bush came to his own decision that Cheney had to be reined in. He turned to other advisers, freezing out and frustrating Cheney, and his administration took on a less arrogant, more measured tone. In Cheney's own autobiography, for example, the former vice president recounts a crucial meeting in 2007 in which Bush and his advisers were debating whether to attack a Syrian nuclear facility.

“I again made the case for U.S. military action against the reactor … But I was a lone voice," Cheney writes. "After I finished, the president asked, ‘Does anyone here agree with the vice president?’ Not a single hand went up around the room.”

Too late. Too late for a lot of things, and a lot of people.

----------

¹The elder Bush does not go so far as to criticize the basic decision to invade Iraq, even though people close to him did so publicly at the time of the debate. “He’s my son, he did his best and I’m for him,” Bush 41 said. “It’s that simple an equation.”