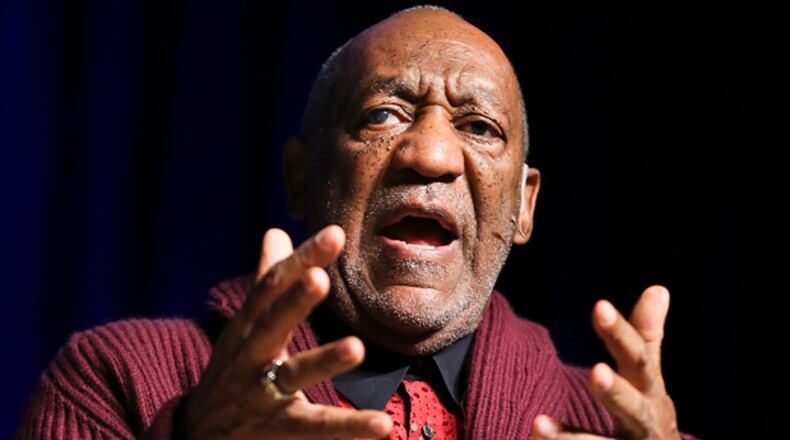

"Bill Cosby is a serial rapist."

I can't pretend to be comfortable writing that sentence. In part, it's the respect and affection I've always had for the man. It's also because the legal system has not come to that conclusion, and as a journalist I'm old school in that regard. I've always been wary about proclaiming guilt or innocence in the absence of a legal finding.

In addition, most of the allegations against Cosby involve actions that took place at least a quarter of a century ago, with no physical evidence to back them up. So even if I do believe that Bill Cosby is a serial rapist, it's unlikely to be proved beyond a reasonable doubt.

But that's the thing: I'm afraid I do believe it. After reading the latest allegation, this one from '70s supermodel and businesswoman Beverly Johnson, I finally realize that I have no choice but to believe it. It's not that Johnson's story, straightforward as it is told by a 62-year-old woman, is somehow more compelling or contains new evidence that previous 20 or so accounts lacked. Instead, it is the mundane quality of Johnson's story that finally convinces.

These stories have come from a variety of women in various walks of life -- actress, model, nurse, mother, athlete, fan. Most are not seeking legal recourse or monetary damages at this late stage; most do not know each other and have little in common except their victimization by what appears to have been a genial, lovable sexual predator with no conscience. (For those looking for more information, a useful timeline and straightforward description of the allegations is here.)

At best, I suppose, you could posit that this is some bizarre psychological phenomenon, some outbreak of mass hysteria affecting individual women all over the country that compels them to direct their pent-up anger at an innocent Cosby. The recent collapse of gang-rape allegations against a University of Virginia fraternity -- a scandal driven largely by journalistic malfeasance and lack of professional skepticism -- argues strongly for caution, as does the rush to convict that unfortunately typifies social media.

Even taking all that into account, though, I'm still left facing the same conclusion. It is plausible that one or two of the many women who have come forward may be later exposed as copy-cat complainants; it is not plausible that most or all fit that description. Too many are telling their truth reluctantly but emphatically and come across as stable, intelligent people.

So if you, like me, reach that conclusion -- "Bill Cosby is a serial rapist" -- what then? Once the revulsion and disbelief at the man's depravity rise up in your throat, once you realize that just seeing his photograph makes you angry and always will, what then?

Personally, I'm struck by the fact that he got away with it for so long, and on such a large scale. How that could happen?

If you read their accounts, Cosby's accusers paint a portrait of a man who was utterly confident that his celebrity and power would protect him. Perhaps more telling, his victims shared that belief. It was unanimous: Predator and prey knew who had the power, and who did not. Even after the attacks, once their heads had cleared and they were out of his grasp, his victims still felt just as helpless against Cosby as they had felt under the influence of the drugs that he had apparently plied so many with.

To a person, his victims believed that if they had gone public, nobody would have believed them; the cost of complaining was much higher than the cost of staying quiet. They felt alone, and the recent discovery that in fact they were not alone, that there were many others like them who shared that experience and shame, seems to have empowered them to now speak up.

But hey, things have changed, right? The timing of these attacks -- all of them apparently occurring in the '60s, '70s and '80s -- allows us to attribute the whole thing to another era that was less enlightened about rape, gender and other issues. No one today could get away with such serial sexual predation now that men and women are on more equitable footing.

Right?

At best, maybe. Certainly, the multiplicity of media now makes it more difficult to suppress stories like this, but it has also made it easier to wallow in sensationalism. The door has opened wider to allegations both true and false, and has made it more difficult to distinguish between the two.

Other things, however, don't change as much as we might want to think. Cosby's humor was founded on a keen power of observation. He had a shrewdness for spotting the gap between what we claim to do and what we really do, and to point it out in a jocular, non-threatening manner that allowed us to laugh at ourselves. The truth now emerging suggests that he also saw a gap between how society claims to treat women and how it really treats women, and he used that insight to cynical advantage.

The basic elements at play here -- misogyny, sex, power, celebrity, wealth, patriarchy, maybe even mental illness -- do not vanish because we wish them to do so. Human beings don't change; we're still the same creatures that we were a thousand years ago, two thousand years ago. What does change is the culture and the rules it sets for how we operate.

We may like to believe that it couldn't happen now. We also believed it couldn't happen then.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured