Girls and minorities need to see themselves in stories solving problems, exploring world

Morgan Young of Atlanta is a former aerospace engineer and the author of "Lana & the Water Carrier," a middle grade novel that features a smart, adventurous African-American girl with a magic telescope, and introduces readers to basic astronomy concepts.

She will be reading from her book at Fernbank Science Center's Astronomy Day program Saturday. Click here for more details.

By Morgan Young

Never underestimate the power of fictional stories in education. Of course, we understand its importance in teaching language arts. But it can also prove useful in teaching math and science. And it just might be the key to getting (and keeping) girls and underrepresented minority students interested in STEM [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics].

The Georgia Department of Education aims to prepare students for careers in the 21st Century workplace by providing quality STEM education opportunities. It defines STEM education as an integrated curriculum driven by “problem solving, discovery, exploratory project/problem-based learning, and student-centered development of ideas and solutions.”

Yet, in a recent survey of Georgia high school students graduating in 2017, nearly 45 percent of boys stated an interest in pursuing STEM careers while roughly 13 percent of girls stated a similar interest.

The same survey showed that Georgia’s graduating African-American students trailed other ethnic groups in stating an interest in STEM, though not as significantly as girls trailed boys.

This should come as no surprise, as women and minorities like African-Americans are underrepresented in STEM fields.

But why the limited interest?

Some have speculated that girls (and children representing certain minority groups, regardless of gender) can’t see or imagine themselves in STEM fields, which have been traditionally dominated by men and looked upon as aspirational for boys.

In my view, if we want girls and underrepresented minority children to become interested in STEM, we need to give them fictional stories to spark their imagination.

We should provide them with engaging stories that depict children like themselves engaged in problem-solving, discovery, exploration, and development of ideas and solutions (Georgia DOE’s very own definition of STEM education).

The idea of using fiction to communicate science-based concepts isn’t novel. We’ve already seen the emergence of “informational fiction” books, where much of the information is factual yet presented through the stories of fictional characters. For example, many teachers and parents are familiar with the Magic School Bus series by Joanna Cole for younger students. And even science-fiction novels like “The Martian” by Andy Weir are useful in helping students to understand real scientific ideas.

I don’t recall reading any books like that while growing up.

Instead, I grew up reading plenty of stories about smart and adventurous children whose names we all know by heart: Tom Sawyer. Huck Finn. Encyclopedia Brown. The Hardy Boys.

All boys. All white.

Very few stories featured smart and adventurous girls as protagonists, much less African-American girls like me. Nancy Drew and Meg from Madeleine L’Engle’s “A Wrinkle in Time” — two white girls — are the only two that come to mind.

I wanted to be Encyclopedia Brown, going around the neighborhood solving problems for other kids using pure logic.

I was smart and adventurous—and labeled a tomboy.

Somehow, I accepted the tomboy moniker with pride. I had no problem doing anything boys could do. That included logic-based subjects like math and science.

But, as an African-American girl growing up, it annoyed me that I NEVER saw any books about girls who looked and acted like me.

Oh sure, I read the civil rights stories and the slavery escape stories. In fact, the stories about Harriett Tubman were the most adventurous ones I ever read. Her actions as she avoided capture while transporting runaway slaves safely to the North were not only heroic and adventurous, but demonstrably smart and logical. Her experiences were also both real and tragic. That removed her stories from the “adventure” category and relegated them to the somber category of non-fiction “black history.”

Today, some things have changed.

For one thing, the “black history” category is decidedly less somber. It now includes fascinating stories about people whose contributions to society may have been previously overlooked. “Hidden Figures,” an inspiring book by Margot Lee Shetterly, highlights a fascinating true story about black women mathematicians who worked on NASA’s Apollo missions. Last year, a film version of the book dazzled the country and inspired many parents to take their children to see it.

For another, the children’s literature landscape is teaming with self-affirming books that encourage black girls to love themselves (their hair, their skin, their noses, and their bodies).

Without question, it is still necessary to help girls, particularly black girls, cope with self-esteem issues that result from a society that has long devalued them.

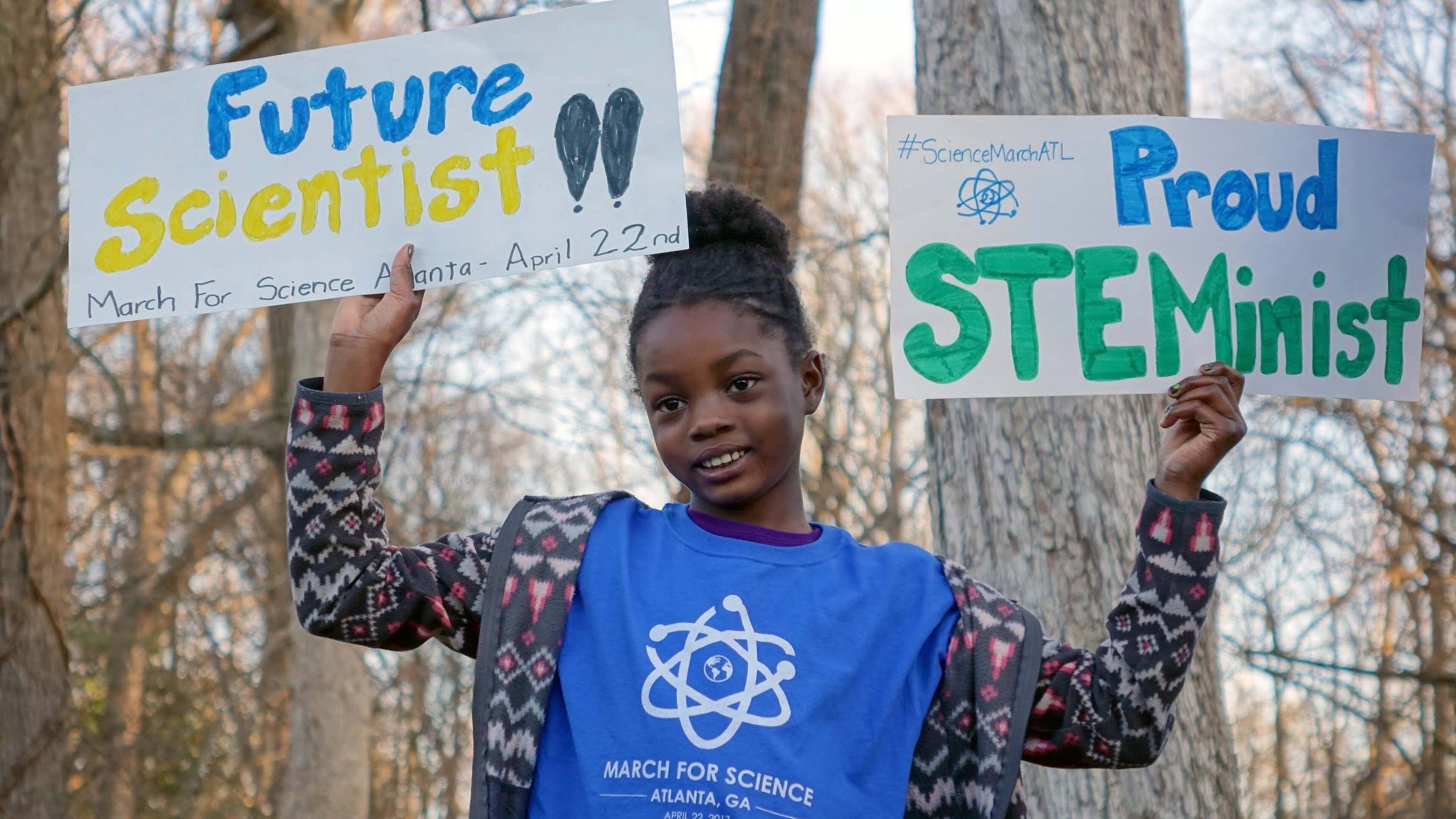

I’m seeing the same trends in terms of encouraging girls into STEM fields, which are still dominated by men. The shelves of libraries and bookstores are lined with books, proclaiming to girls “YOU can be a scientist too.”

Again, it’s a great message.

But that’s not storytelling. That’s proselytizing.

Girls and minority children need to see themselves reflected in books actively doing the things most books only proclaim they can do: problem-solving, discovering, exploring, and developing ideas and solutions.