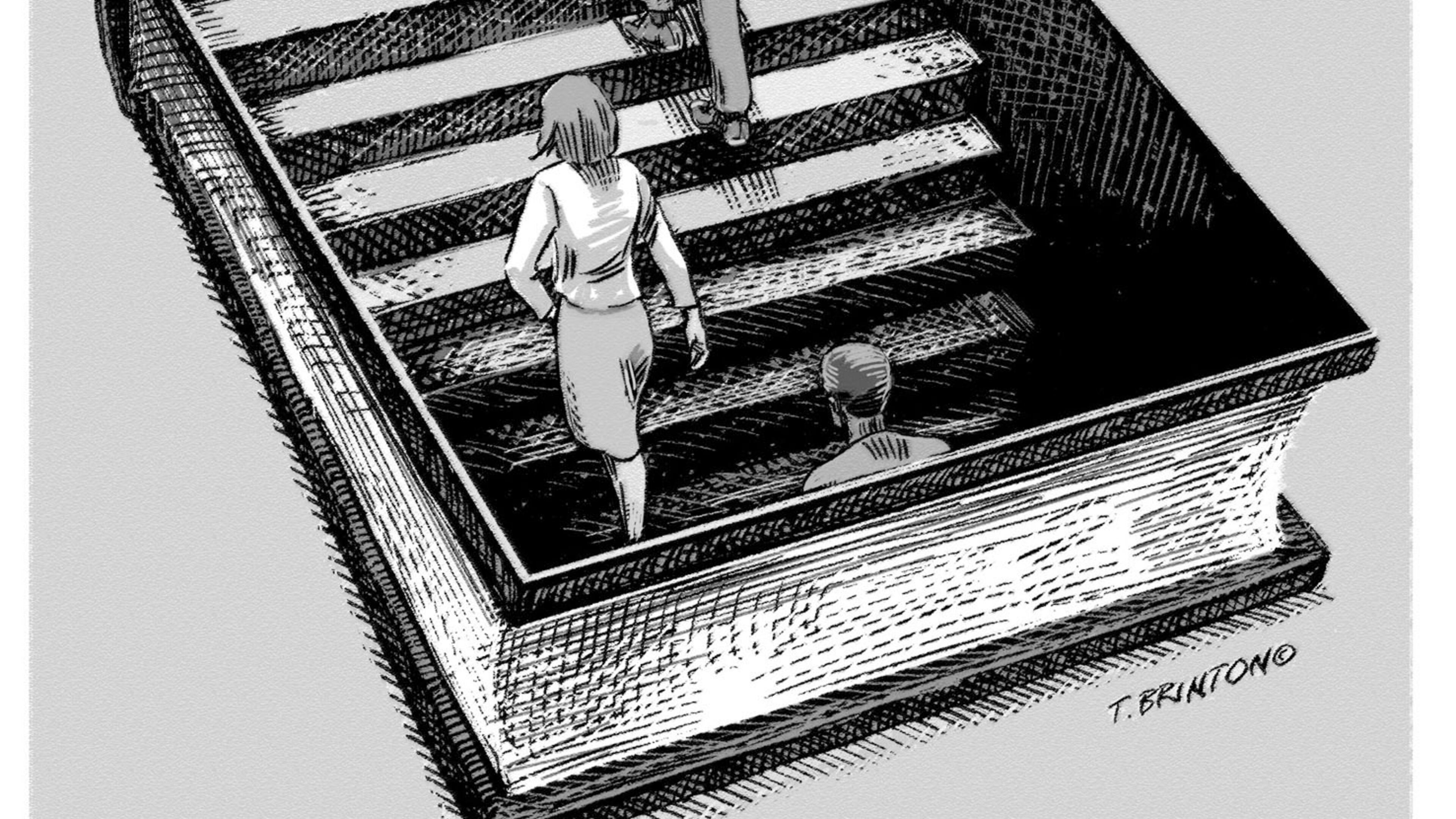

Is college the only path to middle-class for low-income students?

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute is holding an Education for Upward Mobility conference today in Washington around these critical questions: How can we help children born into poverty transcend their disadvantages and enter the middle class as adults? And what role can schools play?

The conference will be opened by Fordham Institute President Michael Petrilli. His opening speech has some interesting observations I wanted to share here. This is a condensed version of his remarks:

By Michael Petrilli

There’s little doubt that education and opportunity are tightly joined in the twenty-first-century economy. Almost every week brings a new study demonstrating that highly skilled workers are rewarded with stronger pay and excellent working conditions, while Americans with few skills are struggling.

Expanding educational achievement, then, is a clear route to expanding economic opportunity. Yet much of our public discourse ends there. Of course more young Americans need better education in order to succeed, especially young Americans growing up in poverty. But what kind of education, and to what end? Is the goal college for all? What do we mean by college? Is that too narrow an objective? How realistic is it? Do our young people mostly need a strong foundation in academics? What role should so-called non-cognitive skills play? Should technical education make a comeback?

After all, current policy stresses getting students college and career ready. But what exactly does that mean — especially the career part? How about apprenticeships? Can we learn from the military’s success in working with disadvantaged youth?

To be sure, schools aren’t the only institutions responsible for boosting upward mobility. Far from it. Yet for years we’ve been having a debate between the education reformers, on one side, and the fix-poverty-first crowd on the other. Like many debates in education, that’s a silly argument, based on a false dichotomy. Of course schools can’t do it alone. But of course schools could be doing more.

And no, boosting upward mobility is not the only purpose of our education system. Every child in America, regardless of his or her socio-economic status, deserves to go to great schools, to be challenged, to learn something new every day.

The genesis of this conference was a gut feeling—a nagging, suspicious feeling—that those of us in the education-reform movement might be barking up the wrong tree. Namely, that we might be overly focused on college as THE pathway to the middle class, and not focused enough on all of the other possible routes.

A few years ago, I decided that I wanted to better understand the anti-poverty literature, so I started talking to people like Ron Haskins, Isabel Sawshill, and Sheldon Danziger, and I asked them what to read, and who else to talk to. What became clear to me is that the anti-poverty community surely doesn’t embrace the college-for-all strategy. I started writing about this, first on Education Week’s Bridging Differences blog with Deborah Meier, and then in outlets like Slate, making the case, as others like Bob Schwartz did long before me, that we need a more balanced approach.

And the reaction from friends was fierce: “You’re giving up on kids,” they said; “would you want anything less than college for your own children, Mike?” they asked; “do you just want to consign people to a life of low wage work and poverty?”

These are good questions, worthy of good answers. Today we’re going to try to find some.

We look at an economy that continues to reward people with college degrees and with measurable skills — and an economy that is punishing people without degrees and without skills. We see a widening gap in this country between the highly educated and the poorly educated — gaps that show up not only in income inequality -- but also in family formation, civic participation, health, happiness, you name it.

So we conclude that we need to get dramatically more young people—and especially low-income young people—into and through higher education. Ideally that means four-year degrees, though two-year degrees and industry credentials are good, too. We firmly believe that a high school diploma is not enough.

My hope is that we can have an honest conversation about these issues and more, and find a middle ground between the utopianism that characterizes so much of the reform movement (“Let’s get every child college and career ready!”) and the defeatism that emanates from too many corners of the education system (“There’s nothing we can do until we end poverty!”).