Swanson comes home amid a world of support, expectation

At about 1:20 a.m. Wednesday, Cooter Swanson’s phone lit up with a message.

Hour away. Doing great. Can’t stop smiling.

The first happy homecoming was near. Cooter had this funny thought: Wasn’t this a little like prom night, waiting there on the couch in the quiet of late night/early morning for his son to get home?

A tick more than an hour later, Sadie, the pit-bull mix, broke into primal song, alerting the house that someone was at the back door. Dansby was home, in Marietta again, a 380-mile drive from Mississippi and Double-A ball behind him and the whole of an uncharted life in major league baseball suddenly spreading out before him.

“I think I’m probably the only guy called up to the big leagues who is staying with his parents,” Dansby Swanson joked.

What do you talk about when you are sitting back at your childhood home, the sound of the road echoing in your skull, but still not quite ready to pull the covers over a day you had spent a young life trying to realize?

“The bottom-line message when we went to bed,” Swanson’s father said, “was don’t worry about all this stuff. You only have one of these (major league debut) games, enjoy that one game.

“We’ve talked about this before. (Dansby) said, look, I’ve already told myself a long time ago I know I’m going to be nervous, so I’m prepared to be nervous. I’ve done this a thousand times in my mind already.”

After a half-hour decompression, Dansby finally went up to his old bedroom, the one decorated in the fancy of a boy: The Duke basketball poster; the youth books on the Yankees’ Derek Jeter and the Red Sox’ Dustin Pedroia; his drawing of Yankees pitcher Andy Pettitte; the photo of his East Cobb team celebrating a tournament win. Only he was the 22-year-old man now, called up to the major leagues to play for the hometown team.

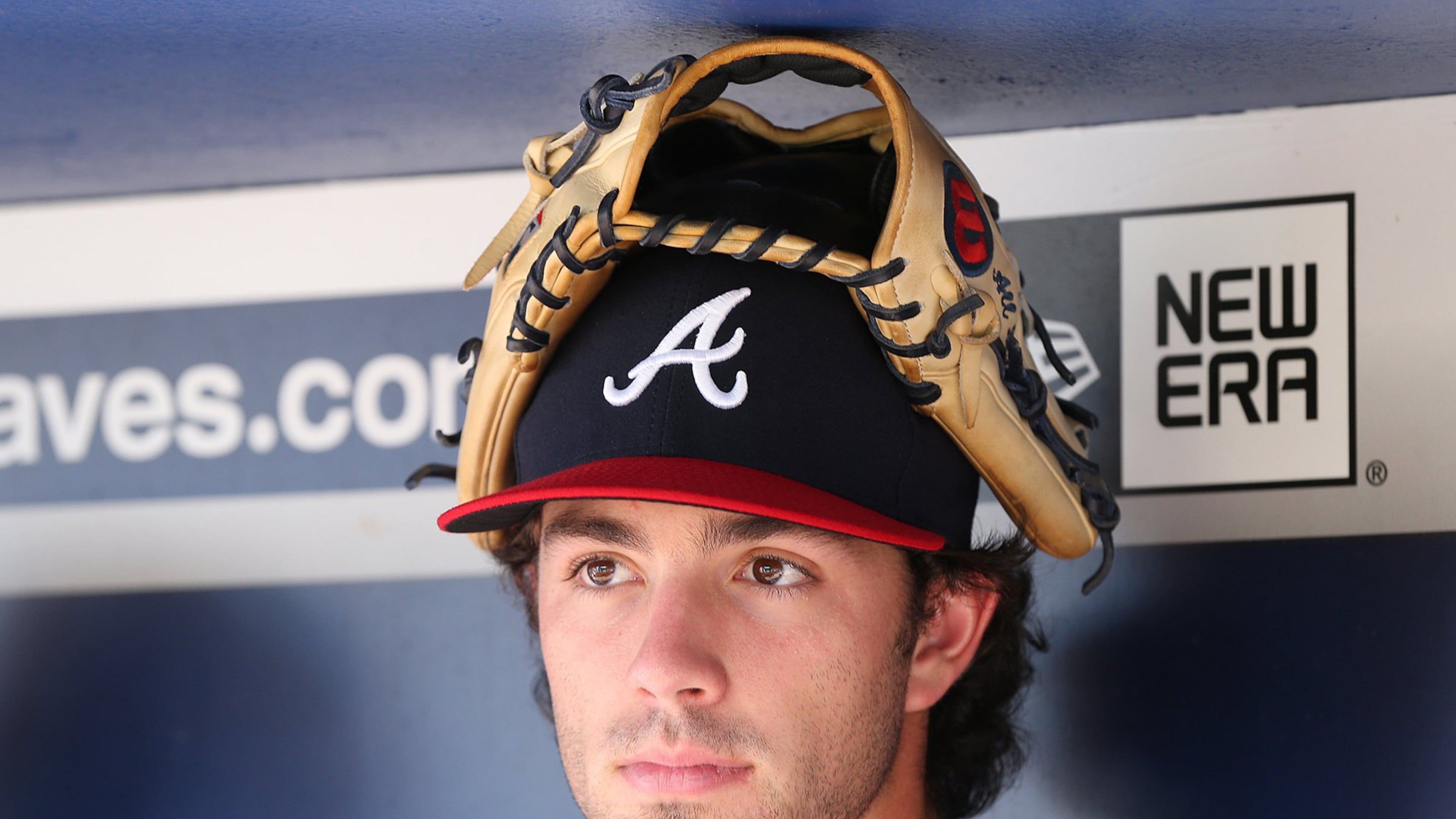

A second homecoming of a sort was official about 14 hours later, when Swanson hit the first step up leading from the Braves’ Turner Field clubhouse tunnel to the field, sun in his face, glove resting playfully atop his cap, all dressed up in his crisp new Atlanta Braves uniform.

“This stuff” as his father put it, is everywhere. So much stuff.

This was no typical major league debut. Awaiting Swanson at the top of the dugout steps, there to record for posterity his first steps upon Turner Field as if he were the Braves’ Neil Armstrong, was a wall of cameras. “Any time we needed to find him (during batting practice) we just looked at which way the cameras were pointed,” his mother, Nancy, joked.

All around the interstates that bind the city, the Braves had posted the billboard message, “Welcome Home Dansby.” That included a portion of northbound I-75, the road leading back to the Swanson home. A big wide road that didn’t exist back when Dansby’s great-great grandfather was selling fuel and sundries in Marietta.

Put it all together. A deeply, devoutly hometown kid. A centerpiece of the Braves’ ambitious reboot. Former top draft pick in all of major league baseball, the first on a Braves roster since Chipper Jones. The symbol of better seasons to come, as the present season molders. Yeah, a lot of stuff.

But as he witnessed the commotion on the field, his father would issue the reminder that this spectacle was still the son of the owner of a custom screen-printing shop and a special-needs teaching assistant. And the younger brother to an attorney who keeps his office near the Marietta Square and to a budding sports psychologist who just finished her doctorate. She has just come back home, too, to work. If it had commissioned and built the Big Chicken this family couldn’t be more tied to Cobb.

“Dansby is just Dansby,” Cooter said. “He’s just like us. He’s like you. I wish people would look at him for what he is. He just happens to play baseball. But he’s also a good person.”

For now he is not allowed the luxury of such simple judgments. There is a franchise to right, and Swanson will be looked at to provide a good deal of the lift.

Starting at shortstop, going 2-for-4 in his debut Wednesday night — everything just about perfect except the result, another Braves loss — was a good start. Neither Swanson nor his parents can clearly recall the first time they brought him to Turner Field as a child to watch the Braves. None, though, are bound to forget his first time here as an employee.

But the pressures will only build from this heady beginning.

Ready, Dansby?

“I have to be, don’t I?”

“Pressure is something that comes about, I guess, when you don’t believe in yourself as much, when you don’t believe this is something you can do or accomplish,” he said.

He says a lot of things like that, and does a lot of things that leave the impression of someone who can think outside the tiny, confining boxes of a baseball scorecard. The Braves are counting on such heightened maturity to see him through the whirlwind to come.

For instance, trying to prepare himself for the first big league at-bat, Swanson visualized it over and over again on the long drive from Mississippi. Hey, it helps to have a sister specializing in sports psychology. And on the drive to the park he even pumped up his walk-up music — Ludacris’ “Georgia” — in order to acclimate himself. So, when the actual moment arrived, when a small crowd made a big noise at his introduction, Swanson said he was not overwhelmed.

“He went to Vanderbilt so he has to be somewhat smart, right?” Jeff Francoeur laughed.

Of all the millions in Atlanta, there is the one guy who understands most what is awaiting Swanson. He was Dansby back when Dansby was only 11. Swanson is travelling a straight parallel line to the one already traveled by Francoeur.

In 2005, Francoeur was the local phenom (Parkview), who drove all night, too, from his Double-A outpost in Alabama to debut in front of a hometown crowd. For good measure, he homered in his first game. And the frenzy was on.

Some of the advice he had for Swanson was light-hearted.

The kid with the thick curly locks needs a haircut Francoeur said, suddenly sounding positively pre-printed circuit.

And he needs to get a place of his own for the duration of the season. Bunking with his parents after the call-up in ’05, Francoeur was subject to fines levied by the Braves clubhouse kangaroo court. That court is always in session.

Some advice was heartfelt. Francoeur, one of the most accommodating players in Braves history, freely admits that he did not always handle the rush of fame well. Huge expectations, including the “Sports Illustrated” cover that labeled him “The Natural,” dissolved into a spotty and well-travelled career that wound its way back to the Braves this season.

“If I could go back 11 years ago, I’d tell the young me that you don’t have to do everything. Just play, be part of a team. Especially off the field,” Francoeur said.

“The next six weeks I’m sure (Swanson’s) going to get bombarded with stuff to do. He’s going to do some stuff and that’s great. But at the same time you’ve got a job to do — to play here and to fit in and make relationships with the guys. That’s probably the most important thing.

“There’s only so much you can do at 22. You got to learn to say no. You got to get your work in, do what you got to do. You can’t do everything.”

But at the same time, you know what? Francoeur is just like the rest of us in one essential way.

“I can’t wait to see what he does,” he said.