'This community is not prepared': Eviction moratorium extension delays inevitable pain for tenants, landlords

Bated breaths turned to sighs of relief Tuesday as the moratorium on COVID-related evictions was extended another 60 days by the Biden administration, protecting nearly 300 Chatham County households facing imminent eviction.

President Joe Biden had indicated earlier this year that he would not seek an extension. The recent spike in COVID-19 infections due to the delta variant, the low rate of nationwide vaccinations, and the restart of in-person schooling across the country prompted the administration to reconsider.

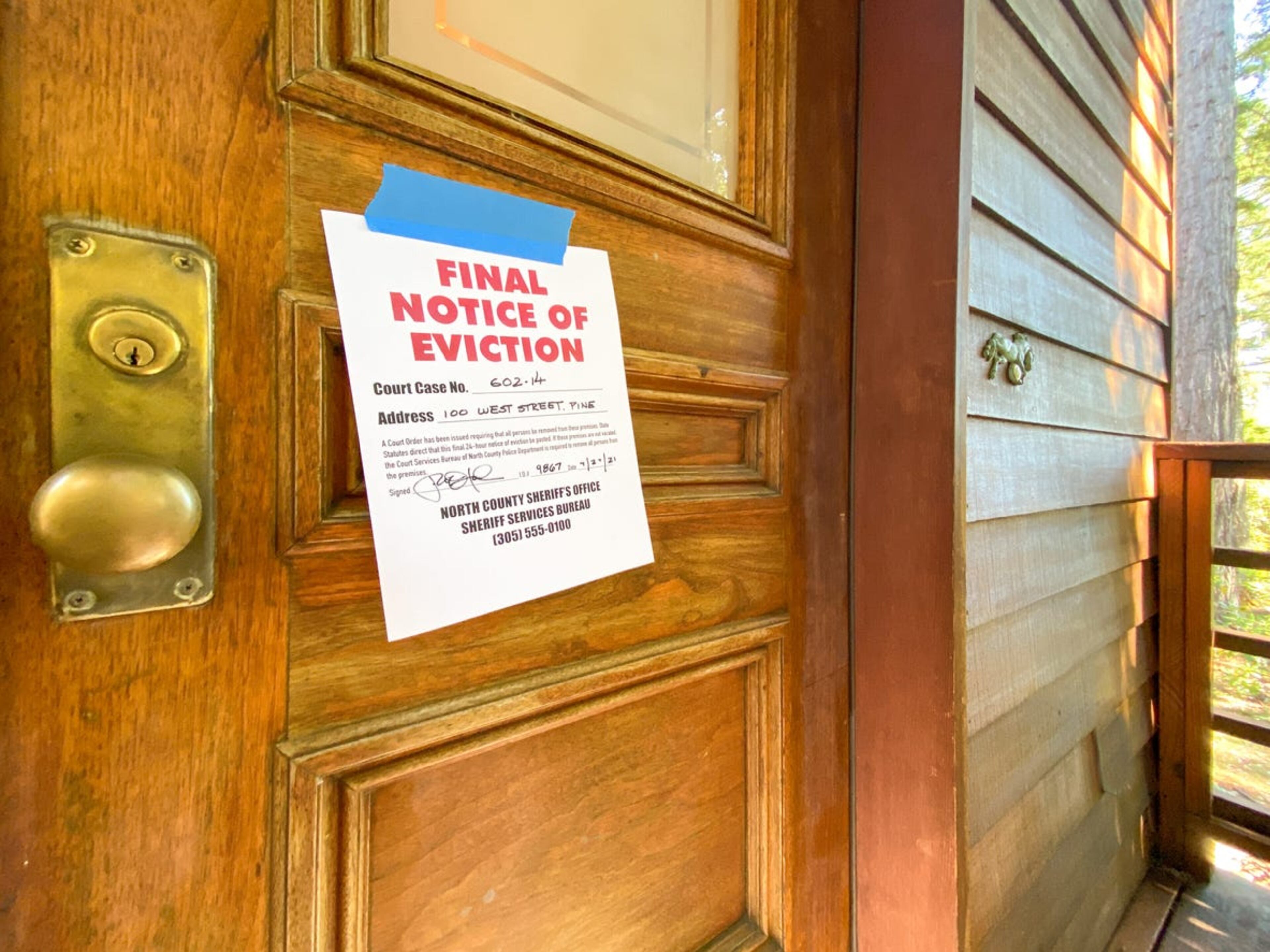

The order delays, but does not prevent a looming crisis — an inevitable wave of renters facing potential homelessness because they cannot pay their bills or rent due to the pandemic wresting away or reducing their incomes. And, the relief from federal Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) funds has not moved quickly enough to cover tenants and landlords.

An estimated 2 million people were protected from eviction due to the original order from the Center's for Disease Control, which stated no evictions would be allowed where a tenant couldn't pay due to COVID-19-related financial hardships. The federal moratorium first went into effect in spring 2020 and has been extended multiple times since.

The protection ended on July 31. Two days later, Biden extended the moratorium another 60 days for areas with high-levels of COVID-19 transmission. Every county in the Coastal Empire qualified, according to the CDC.

The 48 hours between orders bred confusion and stress for both renters and landlords in Chatham County. But, "I don't know of any evictions at this point that were carried out, at least from our caseload," said Shaina Thompson, a housing and eviction rights lawyer for Georgia Legal Services.

The extension is not a cure for the brewing eviction epidemic threatening Savannah. It only allows vital time for renters to apply for available funds, pay outstanding debts to landlords, and find new housing and shelter from the surging virus. It's not a question of if judgment day will come, but when.

What we know about evictions in Savannah

Between mid-June and early July, more than 15% of renters in Georgia classified themselves as "very likely" to be evicted, according to U.S. Census data. County-level data was not available.

The crisis impacted Black renters disproportionately, specifically Black women, according to public health nonprofit Project Hope. Most households living in extreme poverty, meaning a family of three subsists on $10,100 or less a year, regardless of race or gender, were at-risk for eviction in July, according to Census data.

As of July 30, Chatham County Magistrate Court had a backlog of 284 eviction cases to hear, all related to the CDC's order, according to clerk of court Tracie Macke. She told the Savannah Morning News evictions were still happening during the pandemic, they just weren't related to non-payment because of COVID-19.

Nationwide, landlords have filed nearly half a million eviction notices during the pandemic, according to the Eviction Lab.

While the inevitable has been delayed, evictions will begin soon enough.

The reprieve comes at a time when multiple storms are brewing in a city where 60% of eligible people remain unvaccinated. In-person schooling has reconvened, which may help some families resume pre-pandemic work, but also exposes more people to the virus. Wedding and tourist seasons are on the horizon. Rental rates are skyrocketing, and the delta variant is surging, hospitalizing dozens. Coastal Georgia is seeing the year's hottest temperatures, thus far, leading to an increase in heat-related emergencies.

"I'm just going to be totally honest and transparent. The nonprofit community sector is not prepared for it," said Katrina Bostick, executive director of nonprofit Family Promise. "The business world is not prepared, this community is not prepared for that. We can do all we can to help combat it. But I know we don't have enough emergency shelter beds in this community."

Rental assistance in Chatham County

There is help out there for cash-strapped renters, but getting the $8.7 million in federal rental assistance Chatham County received has been slow going.

Since January, Chatham County distributors of Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) funds — federal dollars aimed at easing piled-up bills and rent — has given out $1.3 million to 469 households, according to the U.S. Dept. of Treasury. That's about 15% of the total funds the county received, and United Way and the Economic Opportunity Authority were tasked with dispersing.

The lag in distribution is caused by two things: a lack of awareness from renters and landlords, and a backlog in cases.

"I know there are many households that we have not been able to connect to in this community that need our services. And we want those households to know that we are here, and we want to be able to help them through this rough patch," said Bostick, whose nonprofit, Family Promise, helps United Way with distributing emergency rental assistance.

It's a national problem, according to Jung Choi of the Urban Institute. About 40% of mom-and-pop landlords and more than half of tenants did not know about the federal emergency rental assistance, an Urban Institute survey found.

"There's a lot of people who are still not aware of the support that they can get," Choi said.

And even if renters meet the federal government’s lengthy list of qualifications for ERA, sometimes it’s too late.

“We've also seen where individuals who are at the point of eviction, unfortunately, are waiting to the last minute, and they're already getting the dispossessory warrant, and then it's taking too much time for us to be able to get the assistance, and so evictions are still happening,” United Way’s Jennifer Darsey told the Savannah Morning News last week.

Bostick said the long-term impacts of evictions could prevent a tenant from finding suitable housing in Savannah for the rest of their lives.

An eviction is permanent, as there are no laws in Georgia that allow for eviction expungements.

"It's that constant negative black mark that's on your record now, where potential renters or potential landlords may think that (a tenant) is irresponsible," Bostick said.

'What do we do?'

Evictions set off social and economic spirals that are hard from which to recover. After an eviction, long-term trauma and the dangers of being homeless are their most pressing concerns, Bostick explained. Families may be able to move in with relatives or friends, but many turn to motels when shelter beds are full.

"And when you just think about the number of students in our community who are identified as homeless, it's over 1,200," she said. "So we know we only have 700 beds, and most of those beds are for adults. So what do we do with those 1,200 students, if we have this huge wave of families that are being displaced?"

Motels are typically the only option, other than sleeping outside. Bostick said the temporary housing is a hotbed for crime — drugs, prostitution and trafficking — especially to vulnerable single mothers.

"For children whose mom or dad are working two or three jobs, just to keep them in a hotel, they don't have that parental supervision," Bostick said. "And that is definitely a gateway to sex trafficking for males and females."

According to Human Population Review and the National Human Trafficking Hotline, Georgia ranks among the top 10 states in the nation for human trafficking, with Savannah being a hotspot due to its vicinity to the ports and major highways.

Renting: A two-sided issue

An eviction may seem a clear-cut story of good and evil: a landlord heartlessly kicks a struggling family to the curb, along with all of their belongings.

But the truth is more complicated.

Tom Oxnard, a realtor and landlord who manages about 16 units in the Savannah area, said he hasn't had to evict anyone during the pandemic, but understands the thin operating margins smaller management companies work on.

"Me and all the other landlords who have a dozen tenants, we’re not big multinational corporations. If one or two, three or four people stop paying, it can really affect our business and ability to survive," he said.

For example, Oxnard rents a two-unit house on East 40th Street. He poured thousands of dollars into a renovation of the upstairs unit this year. Without tenants to cover the costs of the mortgage, "I could be down to making a couple thousands bucks in a year, and that’s with a lot of work going into it."

Bill Broker, managing attorney with Georgia Legal Services, said Chatham County has been blessed with understanding landlords and judges, thus far.

"Landlords, they get it. They understand. And the judges here are really good about that. So, that's really not been a problem. It has been in some other jurisdictions. But the judges here have been very, very attentive. They've responded appropriately."

But now when the moratorium ends in 60 days, Broker surmised, "We really don't know what the real reaction is going to be."

Zoe covers Growth & Development and the ripple effects change has on communities and infrastructure in the Savannah area. Find her at znicholson@gannett.com, @zoenicholson_ on Twitter, and @zoenicholsonreporter on Instagram.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: 'This community is not prepared': Eviction moratorium extension delays inevitable pain for tenants, landlords