Editor's Note: One sentence was fixed to clarify that items in the John and Virginia Duncan collection will be available for auction at Everard Auctions this weekend in Savannah.

Though not centrally situated on Monterey Square, the yellow, natural stucco four-story row house at 12 E. Taylor St. certainly has a view of everything. From the large parlor floor windows, a curious person can catch the hustle and bustle of the square — tourists snapping photos in front of Mercer House, worshippers filing into Mikve Israel, horse-drawn carriages clomping, and the not-so-occasional trolley slowing to give a glimpse of history.

For nearly 50 years, John Duncan watched and delighted in Monterey Square's comings and goings, its changes and its scandals. He often stood outside his home, where the garden level doubled as a shop filled with historic ephemera, and regaled tourists with talk of "Midnight" and the unusual historical bits that trolley guides often overlooked. His neighborhood changed over the years, with die-hard downtowners ceding to seasonal renters, and Armstrong students disappearing as pierced-and-tattooed art students passed by with portfolios tucked under their arms.

“He said he always felt like he found Savannah (as) a city of wood and left it a city of stone,” his wife of 46 years, Virginia “Ginger” Duncan, said.

Without John in it, Savannah feels more like sand. John Duncan died on Sept. 21 after a battle with illnesses. He was 84.

Credit: Savannah Morning News File Photo

Credit: Savannah Morning News File Photo

Everybody knew John Duncan at Armstrong College, even the FBI

Armstrong College was founded in 1935 in the white brick mansion at the northwest corner of Bull and Gaston streets. When a lanky 6-foot-7-inch, 27-year-old John Duncan arrived to teach history in the fall of 1965, the college only recently had become a non-residential four-year institution recognized by the University System of Georgia. Along with the fledgling academician arrived the civil rights movement, led in many ways by former Savannah Mayor Otis Johnson, who remembers vividly being the first African American student admitted to Armstrong.

“(John) was one of the initial professors that were cordial to me as I was matriculating over there,” he said. “Some of them went out of their way to be friendly and others just bade their distance. (John) was one who was on the friendly side and that carried over through the years.”

While Johnson said he wouldn’t categorize what Duncan did as extraordinary, the support Duncan and other teachers offered helped Johnson through the college experience.

Credit: savannahnow.com

Credit: savannahnow.com

“He was a liberal. I think it took some courage on the part of white folks to be liberal and to stand up for certain causes. I’m not sure what (political) organization he was a member of, but he let it be known where his politics were, and so I respected him for that.”

Duncan’s height and intellect created a presence around Armstrong and immediately drew Tom Kohler to the history professor when he entered campus in Sept. 1970. “I walked into a Western Civilization 114 class and John was the professor. He was memorable because he was very tall, and immediately irreverent in a sort of wonderful way.”

But it wasn’t just charm and sarcasm that dictated a John Duncan lecture.

“We go to class and he introduces himself, and he explains that many people think that history has been written; it simply is,” Kohler recounted. “Not so. History is evolving. We’re going back, we’re revisiting (and) we’re understanding (history) in different ways. It’s a dynamic and wonderful subject.”

Kohler, a Savannah native said he wasn’t happy to be at the Savannah-based college. He originally wanted to go to the University of Georgia, but that plan didn’t pan out. The flipside: the smaller college allowed more time with the professors, and his time with Professor Duncan fostered a longtime friendship with both John and Ginger once he graduated.

Credit: King/savannahnow.com

Credit: King/savannahnow.com

“John was one of the first adults that I met, where I realized, ‘Oh, you can be like an adult, and be like him,’” he said. “Maybe this isn’t gonna be so bad.”

While Duncan engaged Kohler’s – and many others’ – minds, that didn’t mean the Armstrong professor of 32 years was beloved by all on campus.

“He wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea,” Kohler said. “He once said in class, ‘Let’s get this straight. Jesus was his name and Christ was his game.’ Many people were offended…the class just kind of roiled up, and then he said, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, I’ve just helped you understand the difference in being in high school and in college…

“He said you could have me fired, but we’re in college, and I have something called tenure. So, I get to say what I want to say, and you get to think what you want to think about it.’”

Ginger Duncan said when she met John in 1975, he talked about his long-haired ‘60s days fighting for civil rights in his native Charleston, South Carolina, which garnered the attention of the FBI. “At some point, someone who probably shouldn’t have told him this, told him that he had an FBI file,” Ginger said. “They had read it, and it said that he had colored beads hanging in his apartment. That was his FBI file. He was kind of proud of that.”

Between Duncan’s sympathies towards students such as Johnson and his irreverence in lectures, he would experience some rocky times at Armstrong College, but nothing that ever tipped the boat completely over.

“Although the parents didn’t necessarily respond well to him, he got called into the president’s office a couple of times from parents who were disapproving of ideas that he had presented, or that he didn’t back up what they believed,” Ginger Duncan said. “That was (his) intention. He wanted the students to have to think about it.”

Kohler said he talked a lot with Duncan late in his life about the legacy he would leave — whether it would be the antiques store, his wealth of historical knowledge or his contributions to Savannah. None of those met the mark.

“I taught over 3,000 students at Armstrong; that’s my legacy.”

Giving the writer a look at the Garden of Good and Evil

In the mid-1980s, some writer from New York made his way to the Hostess City, and Ginger Duncan wasn’t immune to the kerfuffle.

“I think we reacted like a lot of civilians did. It was like, ‘Oh, another (writer).’ Because it seemed like for a while there, everybody and his cousin was writing a book about Savannah.”

Both John and Ginger warmed up to John Berendt when they finally met him, and Berendt said he immediately took to John due to his endless knowledge of history.

“One of the things I did (when I got to Savannah), because Jim Williams and Mercer House were right in the center of Monterey Square, (was) I walked to every house on the square and interviewed everybody. That’s how I met John and Ginger. And immediately, he was fascinating,” he said.

John Duncan had one request, however.

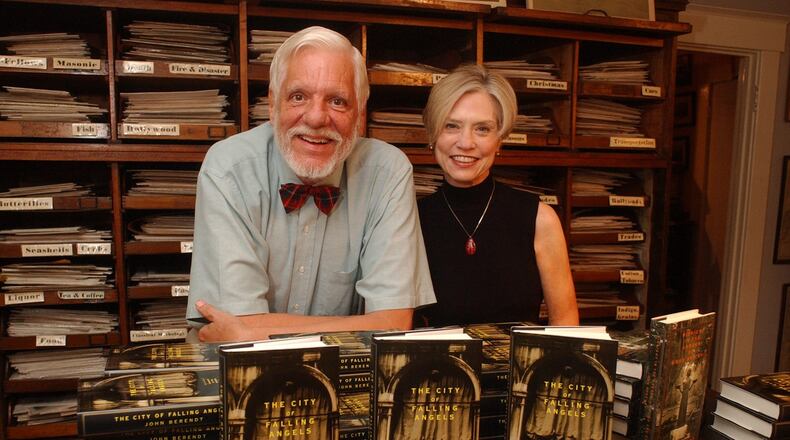

Credit: Richard Sommers/ Savannah Morning News

Credit: Richard Sommers/ Savannah Morning News

“Before I left, he said, ‘If you don’t mind, would you please not mention our name.’ I asked why and he said, ‘Well, you’re passing through doing this book, we have to go on living here when the book comes out.’”

Ginger did not share the same restrictions, Berendt added, and she would go on to make a cameo in both the book version of “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil” and the 1997 movie directed by Clint Eastwood. John, though, despite not wanting a presence in the actual book, developed into a “character” once the book came out and was a hit.

“When the book came out, it was a huge response and people from the newspaper would call and ask him various things. Before he knew it, he was a source of information about the book, and I had never quoted him,” Berendt said. “He was so forthcoming that he was assumed by much of the press media to have been a character in the book.”

Credit: Steve Bisson / Savannah Morning News

Credit: Steve Bisson / Savannah Morning News

Eventually he was: About a year after the book was released in 1994, Duncan appeared alongside the real-life characters in “Midnight” in a one-year retrospective in an issue of the Savannah Morning News.

Berendt said Duncan’s importance to in the process of writing “Midnight” cannot be overstated. He remembered sitting in the Duncans’ East Taylor parlor and reading aloud chapters of “Midnight” once he’d finished writing them. Ginger recalled taking the pages later and reading them as she worked out in the morning, trying her best not to let them fall off the stationary bicycle as she exercised.

Neither John nor Ginger imagined the book would rise to the popularity it did.

“I have to be honest, because of the gay content and the time period it was, (I doubted) that (‘Midnight’) would take off, that it would have any significance,” Ginger said. “We had a small gathering for dinner, and after dinner we toasted and I said, ‘Well, here’s to John’s first week on the New York Times bestseller list.’ And everybody laughed, because that seemed like such an extravagant claim at the time. And then, of course, the rest is history.”

Credit: Courtesy of Everard Auctions

Credit: Courtesy of Everard Auctions

“Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil” dominated the New York Times bestseller list for 216 weeks.

Berendt said that despite his initial request, John Duncan loved the attention after the book brought people in droves to Savannah. “(‘Midnight’) has been described in the press as a love letter to Savannah and (John) felt that way.”

A shop like one you’d find in a London alleyway

Although the East Taylor row house recently sold (though the store is still operational), the V&J Antique Maps sign still hangs above the shop that occupied the garden level of their home.

Longtime friend and Savannah realtor Robert Jones remembers the beginnings of the map emporium because it began in his own antique porcelain shop at 137 Bull St, which the Duncans frequented. “I kept telling him and Ginger that with all these maps and all of his collection, they really should open a shop and they were afraid to do it.”

They finally relented, adding some of their items to a section of Jones’ store.

“John never would fail to say to anybody that was willing to listen (that) we wouldn’t have ever had that business (and) we would never had done what we’ve done without Robert,” Jones said.

Credit: Richard Burkhart/Savannah Morning News

Credit: Richard Burkhart/Savannah Morning News

“Most people don’t remember how something happened. If it goes badly, then they certainly remember, but when it goes well, they forget to credit somebody. John never failed to credit me for getting them started and I appreciate it very much.”

Eventually the Duncans expanded into the ground floor of their residence, where it became known as a treasure trove of all types of history. John sought out the unusual, preferably on a deal, and something unique to the region, Jones said. The three of them traveled to England to find objects to add to their collections and, on occasion, bring objects from Savannah.

“There was a blue and white porcelain bowl at the Davenport House, and when you’d go there on a tour, all the docents would tell you, ‘Oh, this bowl, we think, is probably attributed to [Colonial American potter] Andrew Duche,’” Jones said, before adding. “The bowl was absolutely Chinese; there was no question in the world about it.”

Jones said he convinced a docent friend to allow him to get the bowl appraised on one of his trips to London. In tow were the Duncans to find other items for their collection and the store. The three stayed in an apartment together. Jones came out of his room one morning to find John Duncan eating grits out of the Duche bowl.

“(He had) the biggest grin on his face you have ever seen,” Jones said with a chuckle. And yes, the appraiser confirmed the bowl was of Chinese origin.

Credit: Richard Burkhart/Savannah Morning News

Credit: Richard Burkhart/Savannah Morning News

For David Levy, owner of D Levy Antiques & Appraisals and longtime friend of the Duncans, the store was a unique experience for Savannah residents and visitors because there wasn’t anything quite like it in the region.

“It was just filled to the rafters with old stuff, prints, maps, books as well as photographs and other small items that he might come across…,” Levy described. “He had everything divided into different cities or states, or even colleges, and you’ll have different sections for more natural history-type prints versus prints of famous people or architectural scenes.”

Levy said sometimes folks just stopped by on their way through town while international guests visited the city to see what John and Ginger had to sell. “He had customers that spanned probably decades, people that would come into town, discover the shop (and) come in a few years later, and John would remember they had been there (and) sometimes remember what they had bought.

“He had an incredible memory, and he loved sharing knowledge and sharing what he had, and if he found something and knew you collected it, he would tell you that you had to have it. He wanted you to have it, and you worked out a deal.”

Levy said Duncan encapsulated “the last, true Southern gentleman.”

Credit: Richard Burkhart/Savannah Morning News

Credit: Richard Burkhart/Savannah Morning News

“He had a presence,” he said. “When you opened the door (to the shop), he was sitting right there at the desk and you didn’t realize how big he was until he totally stood up. But he was happy to show people around the shop and tell people where to find something and tell them about it.”

Willis Hakim Jones, Jr. was one of those who received calls from Duncan. Hakim Jones, a collector who credits John for really getting him going, worked at International Paper when he met John Duncan. Because of their shared historical curiosity, they clicked instantly and Duncan took the young historian under his wing to help him navigate the world of antiques.

“He took a lot of time with me, he showed me a lot about collecting and he educated me,” said Hakim Jones, who focuses on regional Black history, specifically items related to the Gullah Geechee.

“‘Don’t try to collect everything,’” Jones remembered Duncan telling him. “He told me to stick with Gullah Geechee, and he was right. I know some well-seasoned collectors that have fabulous collections, but they don’t have the Gullah Geechee story and the Gullah Geechee story is the beginning of African American history in America.”

Past collecting, Jones found inspiration from Duncan as someone who saw promise in him.

Credit: John Carrington / For Savannah Morning News

Credit: John Carrington / For Savannah Morning News

“I used to work at Union Camp and he knew I made a pretty decent salary, and [Duncan] used to say, ‘When are you going to stop making money for those white people?’” said Hakim Jones. “So, I don’t know whether it affected me or not, but my wife and I have had a business for almost 15 years now, and I think partially part of that is because he inspired me to go out on my own. His thing was [African Americans] have been mistreated and cheated, so you need to take advantage of this situation that hasn’t been taken advantage of to the fullest.

“So, he was an inspiration in life, not just education.”

Adding to the collection of the city

A lot of that education is available to everyone now. Make an appointment at the Georgia Historical Society or walk through exhibitions at the Telfair Museums, and John Duncan’s name will probably pop up more often than not. The professor never stopped wielding the lecture notes and providing knowledge for others.

Novelist and founder of The Moth, George Dawes Green, credits John Duncan not only with helping him on his latest novel but also inspiring the premise during a lunch one day.

“I was really interested in the question of marronage, which was the maroon communities in South Carolina and Georgia. So, he mentioned to me that there had been a group of Black soldiers who fought for the King of England in the Revolutionary War, and afterwards, they refused to go back into slavery and that they set-up a community on a swamp island, somewhere around Savannah, and I was so intrigued by it.”

Credit: Courtesy of Celadon Books

Credit: Courtesy of Celadon Books

Duncan gave Green a college paper he had worked on, and after 20 years, Green finally turned the initial piece of history into “The Kingdoms of Savannah.”

“He was always planting seeds and ideas in students and in writers, and he was so good at connecting people not only with ideas, but connecting people with other people.”

For Green, John and Ginger Duncan epitomized Savannah. “I always thought John and Ginger’s house has been the center of this really vibrant, gracious Savannah that we all would love Savannah to be,” he said. “It isn’t always (that) we think of Savannah as this great, gracious place, but some of that is fictional. When you’re at John and Ginger Duncan’s, you always felt like this is just a beautiful community of historians, artists and compassionate people.”

A lifelong Savannahian, Harry DeLorme remembers the extensive work of John Duncan — not just as his late brother’s Armstrong professor but Duncan’s later contributions to Telfair Museums.

DeLorme, Telfair’s director of education and senior curator, said he wasn’t there when John started teaching at Armstrong, but he did get to work closely with the old professor. “I started working with him going back to 1989, 1990, I would say. I curated my first sort of larger exhibition here and John was one of the lenders to that.

“For decades, (John) really was the go-to guy in Savannah for information on the city’s history, particularly on materials, archival materials (and) images related to the city’s history.”

According to Telfair’s records, the Duncans lent 112 items to the museum, including a large collection of glassware and furniture that can be found at Telfair Academy, walking canes from Willis Hakim Jones, Jr., paintings and drawings from Myrtle Jones and Christopher Murphy, and photography of Savannah by George N. Barnard.

DeLorme echoed many others when he said that John had a keen eye for artists, especially those around the region. “He just participated in so many ways to, I think, the culture of the city and his collecting, his research (and) his archives have really contributed a lot to how we understand the city and how we think about the city visually.”

Todd Groce, executive director of the Georgia Historical Society, said the historical knowledge of the city is what Savannah is losing most with Duncan’s passing. He was always someone Groce would send a curious student or visitor to if they had a question that he couldn’t quite nail down.

“I think it’s a loss for them, I mean, we’ve lost a lot of the historical memory of the state. He was here for a long time and he understood the city.

“He was a very shrewd observer of people and I think he could really read people. I think he understood that the real essence of history is people and it’s the story. In history, the word story is in (the name) because it’s about people and it’s about stories, and John could bring out that color.”

The old timbers are falling in Savannah

Ginger Duncan remembers the square around the “Midnight” years. They were familiar and (for the most part) friendly faces.

“I remember I was gonna get some t-shirts made and it was gonna say: 1) the big, red brick house across the square and 2) what kind of dog is that?” she said, remembering how fans of “Midnight” would stop by inquiring where the Mercer House was and what breed their movie star dogs were (trivia answer: Cavalier King Charles Spaniel).

But that all still brought change, Ginger said. “It’s interesting that something (“Midnight”) that reflected so accurately a part of what Savannah was, also changed it so much because of the effect it had on the city; bringing people in and raising property values and the whole business.”

Credit: John Carrington/Savannah Morning News

Credit: John Carrington/Savannah Morning News

“After the book came out, I couldn’t go anywhere without being recognized; restaurants, anywhere. It was always nice to have a little spark of recognition,” said Berendt, a vaunted celebrity after the book was published. “I now have white hair, or what’s left, and some people still recognize me. But I could walk past some people who know the book very well and were very used to seeing my picture in the paper or on TV, who would walk right by me (now).”

Book or no book, people knew and feted John Duncan. He was a professor, a historian, a collector, a father figure, a mentor, a researcher, a personality, a (brief) actor but most importantly, he was a Savannahian.

“The old guard always passes and something new will come, I’m sure it will,” Ginger Duncan said with a sigh. “But it won’t be the same. It won’t be the same city at all.”

Zach Dennis is the editor of the arts and culture section, and weekly Do Savannah alt-weekly publication at the Savannah Morning News. He can be reached at zdennis@savannahnow.com or 912-239-7706.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: 'It won't be the same city at all': Titan of Savannah knowledge John Duncan leaves mammoth legacy

The Latest

Featured