Luxembourg is a vague entity to most Americans, known largely as a rich country somewhere in Europe, a cut-through for the German army on its way to France.

It was early in Randy Evans’ time as ambassador to Luxembourg when he was schooled on another fact about the small nation: It was considered a “Holocaust deadbeat.”

For decades, European nations have reckoned with their part in the mass extermination of Jews during World War II. Sure, the occupying Nazi forces drove the slaughter, but the governments and some residents of those defeated lands bore some responsibility, too. And since the war, European nations have grappled with ways to somehow make amends to the victims and their families.

Evans, a Georgian best known as Newt Gingrich’s lawyer, said when he first arrived in Luxembourg in 2018 as Donald Trump’s appointee, he had listening sessions with representatives of the country’s major religions.

“When I met with the Jewish community, I asked ‘What can I do to help?’ " he recalled. “They said, ‘If you can believe it, Luxembourg is the only (Western European) country to have not made reparations to the Jewish community, especially those who were victims of the Holocaust.’ ”

In 2019, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency news service wrote: “Luxembourg still makes it harder than any other Western European nation for Jews to reclaim property and assets lost under the Nazis.”

Evans was then told a story: He said after the German invasion in May 1940, the Nazis “sent out a letter with the assistance of the Luxembourg government to every Jewish citizen. It basically said that if you send us train fare, we will get you out of the county.”

Evans said many terrified Jewish residents took them up on the offer. “They went to a train station called Cinqfontaines. They were sent to Auschwitz. Imagine paying the fare to your own death.”

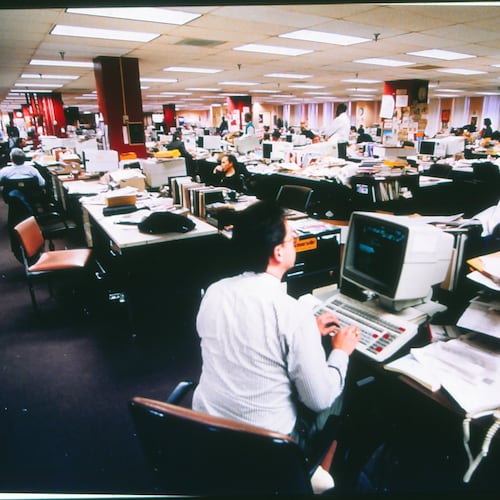

Credit: Public domain

Credit: Public domain

“I was so infuriated that I started beating up the Luxembourg government every day,” Evans said. “I’d do a tweet or include it in a speech. I’d talk about the wrongs that were never righted.”

I met with Evans in his Atlanta law office this week after being told by my reporting colleague Bill Rankin of a fantastic tale. Rankin, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s legal reporter, was interviewing Evans for another story when he asked the lawyer what was he most proud of during his time as an ambassador. Without hesitation, Evans recounted this story.

Another complication, Evans said, was a reluctance in the country’s financial center to open up bank records to investigate the owners of long-dormant bank accounts, presumably those of people now long dead.

“This is how weird it was,” he said, “They were saying ‘You’re going to destroy these banks.’ I said that it’s not the banks’ money, even if the money is still there 75 years later.”

There were perhaps 3,500 Jews in the nation before the war. Many fled, many were sent to death camps. One estimate is that the unretrieved money of Luxembourg Jews could be $500 million. “Seventy-five years of interest is a lot of money,” he said.

“They were accusing me of being a bullying American; they thought I was sticking my nose in someone else’s business,” Evans said. “All I wanted to do was to link them (the descendants) up. Let’s get the money back to who it belongs to.”

“We knew if we didn’t push this, it would never get done,” he said.

Being from the Atlanta area, Evans knows a bit about civil disobedience, even if he is a buttoned down, silk-stocking lawyer. He publicly placed himself in a situation to be noticed near the Luxembourg train station. The local authorities considered arresting him, he said, but there was a thing called diplomatic immunity.

Evans being a pain in the neck eventually helped nudge local authorities to a deal. He showed me photos of his protest. Unfortunately, (for me, that is) he said he forged an agreement with Luxembourg authorities to not publicize exactly what he did or make the photos public. It would help avoid some embarrassment.

The deal was to:

— pay 53 aging Jewish Holocaust survivors each 1 million euros.

— work with the World Jewish Restitution Organization to open up bank records for audits to return assets to the owners or heirs.

— close the train station there and create a research center and memorial to the Holocaust.

Credit: Bill Torpy

Credit: Bill Torpy

Cutting a deal was complicated, he said, because the site was a Catholic monastery and the religious order did not want to give up the site. He added the government did not want to have the deal be an implicit admission that Luxembourg was guilty of atrocity. “There’s a feeling there that ’We were victims, too,’ “ Evans said.

This is where having good attorneys involved in a deal pays dividends. The property was divided up between the religious entity’s land and the government’s, although the land was deeded to the ministry of tourism, which is somehow one step removed from official government ownership.

For his work, Evans was given a 19th Century Hebrew Bible that he keeps in his office and a letter from Francois Moyse, a Luxembourg lawyer who helped carve out the deal, calling the former ambassador a “true hero of the Jewish people.”

I asked Evans what he thought of where we are today, having immersed himself in this age-old saga.

“I travelled all the counties in Europe and have found that anti-Semitism is as bad now as I’ve seen,” he said. “It’s on the rise. And it’s scary.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured